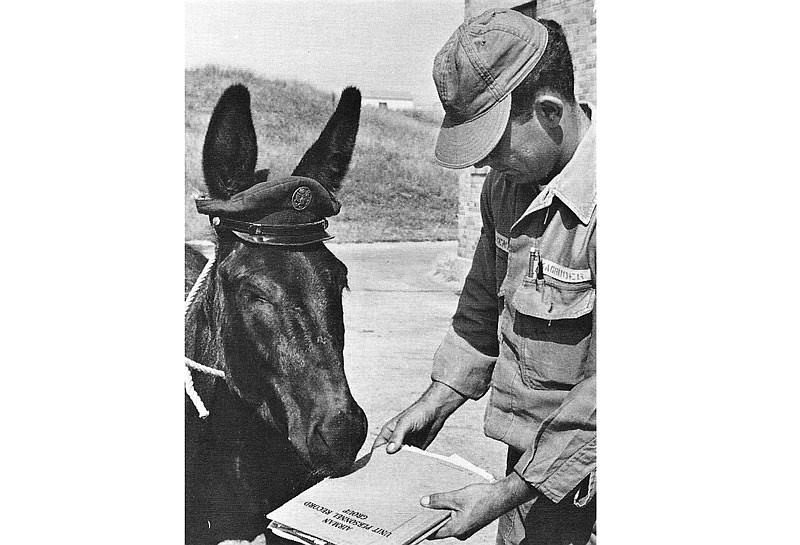

For more than a decade, a Missouri mule served as a mascot for an Air National Guard squadron, entertaining countless spectators in parades and even participating in the inauguration of governors.

On other occasions, he captured newspaper headlines throughout the United States when traveling to military training exercises and was later denied the opportunity to deploy to France with his fellow airmen.

The origins of the 110th Fighter Squadron date back to 1923, when it began its military legacy as the 110th Observation Squadron with headquarters located at a filling station on Manchester Road in St. Louis.

The squadron counted among its distinguished members famed aviator Charles Lindbergh and adopted as its insignia the fighting Missouri mule, which wore aviator goggles and breathed fire through its nostrils

"Living up to a legend is no cinch," wrote Theodore Wagner in the Nov. 4, 1959, edition of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. "Banjo A. Burro, mascot of the 110th Tactical Fighter Squadron, Lambert-St. Louis Field, learned quickly this last summer after leaving the quiet of a Jefferson County hillside for a hurly-burly life with the Missouri Air National Guard."

"The Show Me Spirit," which was published in 1973 and chronicled the then-50-year history of the Missouri Air National Guard, explained Banjo was a Missouri mule "(e)nlisted by Col. Robert Smith, then a major and commander of the 110th Fighter Squadron, (who) found a new niche in life at the National Guard base at Lambert Field."

Banjo wasted little time in demonstrating his unique personality and skills as an escape artist when finding his way out of the pen that was specifically built for him on the National Guard base in St. Louis.

The aforementioned book explained, " early in his career, Banjo decided to go AWOL. He broke out of his billet one morning at 2:30 and wandered onto the nearby runway, shocking civilian control tower personnel. It took several Air Guard Security Police and an airport officer to return him to his barracks."

Obtained by the squadron at the cost of $75, Banjo quickly became one of the most celebrated members of the Missouri National Guard.

During the inauguration of Gov. John Dalton on Jan. 9, 1961, the mule loped by the review stand, seemingly unimpressed by onlookers that included not only the governor, but state officials and former President Harry S. Truman.

Banjo A. Burro's outfit for special events helped him appear "resplendent in a gaudy blanket and a jaunty red flight cap, his long ears stuck through holes in the cap," reported the St. Louis Post-Dispatch on Nov. 4, 1959.

When the squadron traveled to their summer encampments, Banjo was loaded on a private trailer and attended the training exercises alongside his fellow airmen. Reports stated during off-duty hours, Banjo gained the reputation of enjoying the occasional beer and chewing on the finest of cigars.

St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported Nov. 5, 1961, even though Banjo was frequently honored, he possessed a wild streak and stubborn nature which inhibited his promotion potential.

The paper explained, "He even earned a number of citations from state and federal officials, but he remains 'Airman Basic Burro,' after having been broken in rank repeatedly as result of his indifference to the rules. These frailties, and a frolicsome disposition, endeared him to the men of the squadron "

Proving he was more than a mere Missouri mule, Banjo made the headlines of newspapers throughout the country when he was temporarily removed from his military duties after the squadron received mobilization orders in response to the Berlin Crisis.

"Banjo A. Burro is a Missouri mule on furlough," wrote the Sacramento Bee on Jan. 4, 1962. "Banjo is the mascot of the St. Louis-based Missouri Air National Guard squadron recently called up for active duty in France. The squadron wanted to take Banjo along, but the brass refused."

Linda Drullinger, whose late father was a steam plant operator for the Air National Guard at Lambert, explained, "When the Guard deployed to France, my dad had a barn and a lot of acres in Wentzville that Banjo could run around on, so he was moved there."

She continued, "One thing is for sure - he had a mind of his own. When I was a kid, I would try to ride him and sometimes he would go as slow as a turtle, but when I would turn him back toward the barn, he would take off in a gallop."

The mule, Drullinger recalled, got along well with the pigs and chickens on their father's property but, despite any barnyard friendships, frequently found ways to escape his fenced surroundings.

"When he'd get out, we'd have to chase him down and once we caught him, he'd kind of laugh at us because he knew we were taking him back to the barn," she said.

Following the squadron's return from France in late summer of 1962, Banjo continued to live on the farm near Wentzville. He would remain the mascot for the squadron and continue to participate in parades while also receiving escort to annual training events in a private trailer.

Having spent more than a decade symbolizing the "Fighting Missouri Mule," Banjo escaped a final time from the farm and was struck by a car in early 1970. Due to the extent of his injuries, the 18-year-old mascot had to be put down by a local veterinarian.

"When he first came to the farm, I can remember my little brother and I were walking through the gate and Banjo came running toward us," Drullinger recalled. "It startled me and I was able to push my brother through the gate to safety, but I didn't have time to get away."

She concluded, "But when he got to me, he just stopped and stood there with a goofy look on his face." Grinning she, added," He was certainly a joker and is greatly missed."

Jeremy P. Amick writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.