The headstone of Sally Burr sits at Woodland-Old City Cemetery under a shade tree. Unmarked beside her is buried her husband and murderer, Dedimus Buell Burr.

She died Feb. 14, 1842, after an illness at the age of 29.

During her funeral procession, Burr's apprentice happened to ask if glass was an ingredient for mixing paint.

That set off suspicions that led to an autopsy, which found "a considerable quantity of pounded glass in her stomach and bowels, sufficient to cause death." Apparently, he had been mixing it in with her food for more than a week.

Ironically, two years earlier, in 1840, Burr, with partners James Crump and John Rogers, had been contracted for construction of the jail he sat in for five months before his execution.

The couple were known to argue frequently in their small frame house on East High Street. Sally was Burr's second wife, with suspicions he had taken the life of his first wife, too.

Printer Albert G. Baber was attributed with convincing Burr to confess.

The week-long trial in May 1842 ended with the judge's sentence of execution by hanging July 8, 1842. Prosecutors were S.M. Bay and E.L. Edwards. Attorneys for the defense were W.G. Minor, Mr. Leonard and Mr. Lisle.

"No doubt exists in the mind of the community as to the justness of the conviction," the Jefferson Enquirer reported.

The newspaper printed a great portion of Judge James Morrow's pronouncement: "You have been pronounced guilty of a crime, the moral enormity of which can scarcely be paralleled in the annals of fiendishness and cruelty one of the most extraordinary features in this case is, the apparent absence of all motive for the commission of the deed - that you had a motive, and that motive the strongest that could move the foul passions of your nature, there can be no doubt. What that motive was is known, perhaps, only to yourself and your God."

Gov. Thomas Reynolds received many requests to commute the sentence, which he refused.

The gallows were built just west of the Woodland-Old City Cemetery. Burr was driven by farm wagon there, where he made no statement and died "stoically and without evident fear," a 1936 News Tribune said. However, Mark Schreiber in his "Somewhere In Time, 170 Years of Missouri Corrections" says the "condemned man made a short speech confessed, repented and expressed hope of forgiveness. (He) admonished the audience to learn from his example."

Farmers from the outlying area came to town for the hanging, circling their wagons around the gallows. Prisoners from the nearby Missouri State Penitentiary were allowed to join the large number of townspeople to watch the execution. It was only the third in the city's short history and the first not to involve an inmate at the prison.

In Ford's History of Jefferson City, written in 1938, architect Frank B. Miller said the event was still talked about for decades after.

Burr was born in 1813 in Haddam, Connecticut, the son of a War of 1812 veteran. At age 3, he was orphaned when his parents died one day apart in 1816. He was the youngest of five children and became the ward of his maternal grandfather, Didymus Johnson, until his death in 1833.

Then he became the ward of his brother-in-law, John Clark. The Clarks left the Congregational Church in 1836, after being baptized into the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Burr, age 21, moved with the Clarks in July 1836 to Kirtland, Ohio, where John and Maria received a patriarchal blessing from Joseph Smith Sr. and John was ordained as an elder. Less than two years later, they again traveled with the Kirtland Saints to Caldwell County, Missouri.

John Clark, a master stone cutter, lost his home and land in Caldwell County in the 1838 expulsion of Mormons by Gov. Lilburn Boggs. It is likely this is when Burr and the Clarks went separate ways. Maria and her five children spent the winter in Quincy, Illinois, while John Clark, and likely Burr, worked on bridges for the Central Illinois Railroad. However, John and two children died of bilious fever in 1839. Maria and her remaining children moved to Nauvoo, Illinois.

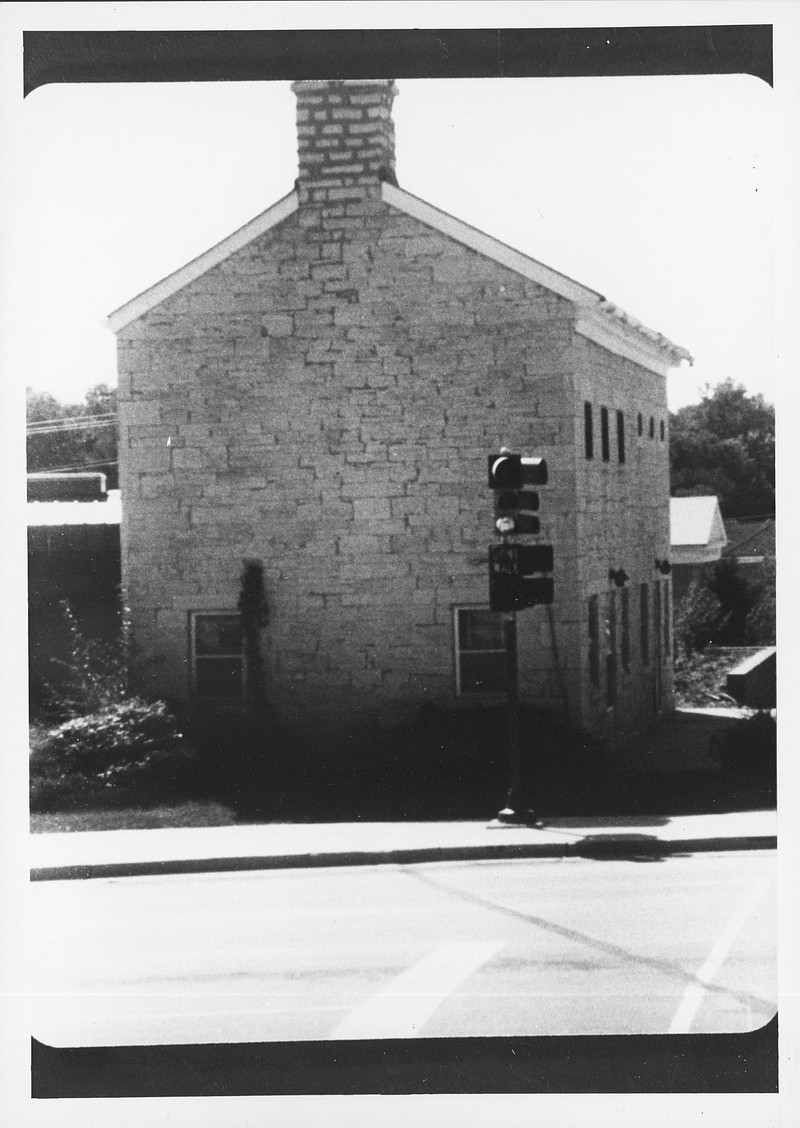

Burr arrived in Jefferson City by 1840, when the census lists him employed in manufacture and trade and owning four enslaved people. He was a prominent and skilled cabinet maker and wood carver, who had been consulted for several buildings in those early days including that jail house on Monroe Street where he would spend the last few months of his life.

Michelle Brooks is a former reporter for the Jefferson City News Tribune. She has been researching Jefferson City history for more than a decade and is especially interested in the first century of Lincoln University.