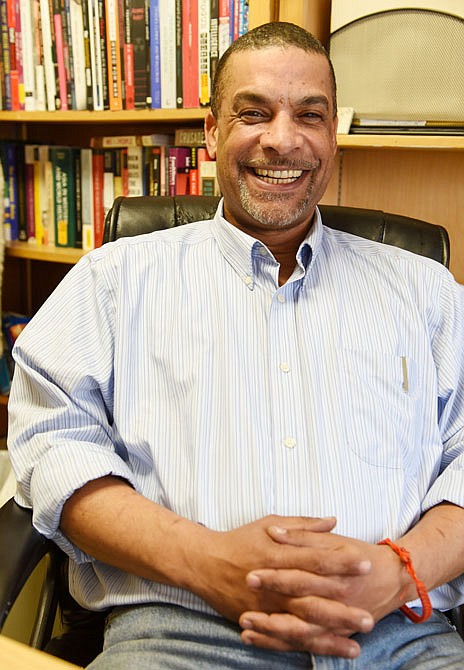

Lincoln University professor Darius Watson dropped out of high school as an honors student with only seven weeks until graduation.

It was during the crack epidemic of the mid-1980s, which deeply affected his community in Poughkeepsie, New York. This, along with a lack of structure at home, led him to struggle with drug addiction and get wrapped up in criminal activity.

"It was living between worlds," Watson said. "I'd literally be in classes and it'd just be me and all these advanced regions and honors courses, and I'm just the token. It's me and maybe 15, 20 white students, and I'd put all my books in my locker and I'd go down to Main Street, get my package and engage in a bunch of criminal activity. And yeah, it ended up kind of wrecking my whole youth."

Watson's mother suffered significant abuse when she was younger, causing her to struggle with multiple personality disorder. But, growing up, Watson didn't know she had a mental disability. She was diagnosed after he dropped out of school and moved away for three years.

"I had to always be on my toes," he said. "I knew something wasn't right, but I never knew what."

He worked at restaurants from age 15 until about 35 - a year before he earned his doctorate in international relations and foreign policy.

"I worked really hard to become a decent man, to become a good man, but I've always been driven by the belief that I was meant to be a great man - and that meant something more."

Watson earned his GED when he was 21, and he overcame his addiction two years later. It took him six and a half years to get his two-year degree, but four and a half years later, he earned his master's. He was 35, attending graduate school while working at a restaurant full time and raising two children.

"I gained momentum and started pushing forward once I got rid of a lot of the baggage of my youth," he said.

Watson found his passion for international relations and foreign policy when he took a class that participated in a mock United Nations event in New York City with about 5,000 students from around the world.

"It was the most transformative experience I've ever had," he said. "I was in action. The diplomacy aspect, the studying, the research, the formulation of resolutions - I just was good at it."

He quickly became a teaching assistant. He knew he wanted to be a teacher when he was working alongside amazing professors, yet he was the one helping students understand concepts.

"The look on a student's face when they get it, and I know I'm the one that helped them get it, and now all of a sudden they're excited about the next thing - that, to me, was like, it was a new drug," Watson said. "I could use that passion and now start to put aside some of the other things."

After that, he worked as a visiting instructor at Union College in Schenectady, New York, where he developed his own United Nations program that became one of the top five delegations in the world.

Watson's office shelves are filled with knickknacks his students bought for him while traveling the world for their jobs, doing things he's always dreamed of doing.

"I've lived a lot of my life through others, whether it's historians or students," he said. "I am hoping that I'm entering a phase of my life where I finally get to do it myself."

Watson has dreamed of writing a book about his life, starting a coral farm in Indonesia, starring in nature and travel documentaries, and becoming the 'Neil DeGrasse Tyson of political science,'" he said.

"To me, the sky's the limit, and I want to make a difference," he said. "A real difference. I just want things to be better after I go than they were when I showed up. I don't care where or when or how. I just want to make a difference. I don't want to be one of these people that's just riding in the back of the car."

After earning his doctorate, Watson moved to Nebraska and worked as a professor. His wife is from Nebraska, and he wanted his children to live close to their grandparents and other family members.

"I wanted my children to grow up with a secondary level of family that I didn't have," he said. "But it was a sacrifice for me personally and professionally."

Not realizing how different the Midwest is from New York, he experienced culture shock the entire time he lived there.

"I didn't realize how much of a New Yorker I was until I moved," he said. "And I wasn't just a New Yorker. I was the loud-mouth, opinionated, black liberal."

Three weeks after student protests and racial climate concerns that led then-University of Missouri System President Tim Wolfe to resign, the university Watson worked at had a faculty meeting.

A leader at the university stood in front of the faculty, Watson said, and said, "No matter what we do, we have to make sure those people don't come here."

"So as one of two African-American faculty in a room of 100 people, (I thought) what do you mean by 'those people'?" Watson said.

He acknowledged it became a contentious relationship between him and the school's leadership.

"They literally paid me not to work there for a year because they did not like the fact that I'm not going to just sit there," he said.

He said he tried to find other work in Nebraska but was unsuccessful. Sitting in his basement by himself, unemployed, with no friends, he had to find hobbies.

"I just did not fit in, in any way, shape or form," he said.

He began writing articles online. He began collecting coral, fish and sea anemones. Fascinated, he learned everything he could about them and decided to turn it into a business. He researched international coral markets, created a business proposal, got an import license to ship coral from Indonesia, spent about $10,000 on tanks and equipment, and sent $5,000 to an exporter in Indonesia.

Three weeks later, Indonesia closed off all coral shipment, and he never heard from the exporter again. His money was gone, and he lost his business before it could even begin.

"As bad as things were at the former job, that was probably one of the lowest points in my life," he said. "I can't get a freaking job. I can't make this coral business. What am I going to do with my life? Honestly, this time a year ago, I found myself asking the question, am I even still a professor? I can't get anybody to hire me. No one appreciates what I'm doing. You want to try and break out into something new, it falls apart. I thought I was cursed."

He was one of the highest rated professors at every school he's taught at, but he didn't have the publication record schools were looking for, he said.

After a year and a half, he was hired at Lincoln University, and his life completely changed.

"Maybe I went through everything so that I'd be fully prepared for this," Watson said. "And so I have hit the ground running. I have accomplished more in six months here than I accomplished in six years at my old job."

While New York is diverse, Watson compared its diversity to a quilt - each individual patch is unique. He said Missouri is one of the most diverse places he's ever been.

"This is one of the first areas that I've ever been where the diversity seems to directly lead to interest and inclusion," he said. "I've never had so many, frankly, white Americans be interested in my story."

At 49 years old, Watson has finally found himself. He's finally found a place where he fits in and belongs. He's finally found a home.

"I didn't realize how much I didn't have a home until I came here," he said. "It's amazing to find a place where I can engage my passion for knowledge and education and have that same engagement given back to me."

With his newfound liberation, Watson has a chance to make a difference.

"Passion without belonging leaves you running in circles, trying to put out fires, trying to get anybody to listen," he said. "And now that I belong, I'm able to channel it, because there is no such thing as a limit for me. I've been waiting for this my whole life, so you know what, if I've got to work 23 hours a day, I'll do it. Whatever it takes to get where I need to go."