The "Jefferson City Mohawks reigned as king of baseball in Jefferson City." That quote ran in a 1969 News Tribune sports feature more than 40 years after the team was organized.

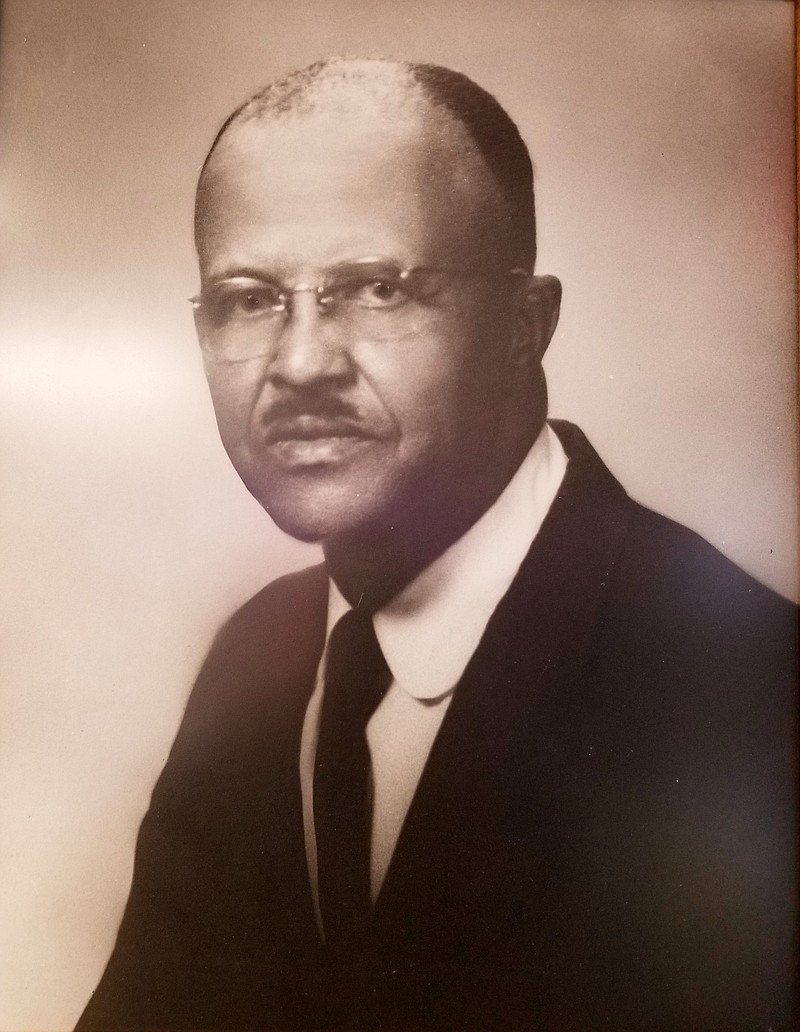

Charles "Lefty" Robinson was the pitcher and later manager for the impressive team of black players who took on exhibition games with American Negro Baseball League teams, including the Kansas City Monarchs, St. Louis Stars and Birmingham Black Barons, as the professionals traveled across the state.

The Mohawks hosted the 1932 Negro Baseball Championships of Central Missouri at Whiteway Park. But more often, they played at Lincoln Park, enclosed by a board fence near Lincoln University's practice field, according to Gary Kremer.

Before the Mohawks organized in 1922, the Jefferson City Hubs were the big team for black players. But they only had two local players. After the locally filled Mohawks beat the Hubs twice decisively in the 1920s, the Hubs team disbanded.

Later, Lincoln University also manned a competitive team called the Jefferson City Eagles. In the 1950s, the Mohawks and Eagles combined as the Dodgers to play in the new Central Missouri Negro League.

Robinson gained notoriety for his left-handed pitching.

"I learned to throw the curve by watching a crippled man in my hometown of New London - something was wrong with his hand and his thumb stuck straight up in the air," Robinson said.

He went home and modeled his style after the man, throwing in a walnut grove behind his home. "A big smile broke across 'Lefty's' face as he paused, then, 'Why, that ball started out on one side of that tree, curved all the way and came out on the other side of the tree.'"

But he eventually had to learn to throw the curveball the right way, as batters learned to anticipate the curve ball when they saw his thumb up.

The 1921, Daily Capital News called him "one of the best colored pitchers in the country." He pitched his first no-run, no-hit game in June 1929 at Linn, 21-0. By May 1930, the Post Tribune called Robinson "ancient."

He was invited to pitch full time with the St. Louis Stars, taking the job for one month in 1924. "But I quit because I was making more money working at the Capitol," Robinson said. Proud to be a Christian and holding to high morals, he said he didn't want to desert his family, either.

Robinson wasn't the only team standout. As a whole, the Daily Capital News said the Mohawks were "Missouri's fastest colored team in the semi-professional class." Centerfielder Bud Rankin had his share of long drives from the plate. And shortstop Willie Smith was quite the slugger, too.

Lincoln University student Ralph Shropshire was catcher when not giving a "heavy hitting exhibition," and he went on to be catcher for the St. Louis Stars in 1937.

They also played white teams, like the local Senators or Crevelts, or when competing in the State Semi-Professional Tournament.

Local ball games often featured live music before a game and in between innings. Robinson and his string band or his Jubilee Singers performed at many of the white ball games.

By the 1930s, Robinson moved into a management role for the Mohawks, with his son Charles Jr., taking over the pitching.

Robinson also was a leader in the community, presiding over meetings of the young Negro Republicans at the Washington School and serving 15 years as president of the Jefferson City Community Center Association.

When the white community was debating a recreation center for boys, Robinson told them "no colored youngsters have been in trouble since the center was established and urged that a similar program be instituted for white youth," the Post Tribune reported on Feb. 17, 1950.

He was active in the area Republican party, serving as a delegate to the 1960 national convention. He was the first black man in modern times to be listed on the city ballot, though he lost to the incumbent city assessor in 1961.

Robinson was a charter member of the Jefferson City chapter of the NAACP, serving 27 years as chapter treasurer. Gov. Christopher Bond proclaimed Nov. 4, 1975, as Charles E. "Lefty" Robinson Day at the 18th annual Freedom Dinner.

He also volunteered 18 years with the Community Chest and with the Boy Scouts. And he organized the first day nursery for working moms.

He came to Jefferson City in 1912 to work in Gov. Arthur Hyde's administration, then was the first black employee for the state workmen's compensation commission in 1922. He clerked for the food and drug department and the Senate before working at Lincoln University in the 1950s, and retired as a funeral director.

The city's JeffTran headquarters at 820 E. Miller St. is named for Robinson.

Michelle Brooks is a former reporter for the Jefferson City News Tribune. She has been researching Jefferson City history for more than a decade and is especially interested in the first century of Lincoln University.