The Johnson Amendment has been back in the news in recent years including reports that Missouri attorney general - and U.S. Senate candidate - Josh Hawley told religious leaders meeting in St. Louis last month that the amendment should be repealed.

Eric Mee, press secretary for U.S. Sen. Claire McCaskill - the incumbent Democrat who Republican Hawley wishes to replace - told the News Tribune that McCaskill opposes repealing the Johnson Amendment.

But Hawley told the News Tribune last week: "I absolutely agree that the Johnson Amendment should be repealed. Any attempt to penalize pastors and churches, for preaching what they believe, is a violation of our First Amendment rights."

Now-President Donald Trump said something similar in July 2016, as he accepted the Republican Party's nomination for the presidency and thanked "the evangelical and religious community" for their assistance in getting him nominated.

"They have much to contribute to our politics, yet our laws prevent you from speaking your minds from your own pulpits," he said during his acceptance speech. "An amendment, pushed by Lyndon Johnson many years ago, threatens religious institutions with a loss of their tax-exempt status if they openly advocate their political views. Their voice has been taken away.

"I am going to work very hard to repeal that language and to protect free speech for all Americans."

How it became federal law

In 1954, Lyndon Baines Johnson - the Texas Democrat who would become vice president in 1961 and president when John Kennedy was assassinated in 1963 - was the U.S. Senate's minority leader.

He also was involved in a re-election campaign that year where - the New York Times explained in a Feb. 2, 2017, article - two conservative, "nonprofit groups were campaigning against him by suggesting he was a Communist."

A Politifact article from July 22, 2016 - shortly after Trump's convention acceptance speech - said the groups also "wanted to limit the treaty-making ability of the president (and) produced material that called for electing (Johnson's) primary opponent."

So Johnson introduced a bill in Congress 64 years ago, changing the existing Internal Revenue Service law in the 501(c)(3) section, which covers tax-exempt charitable organizations.

Johnson's new language said, "in effect, that if you want to be absolved from paying taxes, you couldn't be involved in partisan politics," according to the Politifact article.

On its website the Internal Revenue Service notes: "Currently, the law prohibits political campaign activity by charities and churches by defining a 501(c)(3) organization as one 'which does not participate in, or intervene in (including the publishing or distributing of statements), any political campaign on behalf of (or in opposition to) any candidate for public office.'

"To the extent Congress has revisited the ban over the years, it has in fact strengthened the ban. The most recent change came in 1987 when Congress amended the language to clarify that the prohibition also applies to statements opposing candidates."

In 1954, Republicans controlled the Congress that passed it.

Republican President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed it into law.

There was no record of any debate in 1954 around the amendment to the federal tax code, which has become known as the Johnson Amendment.

Growing opposition

But the debate has grown in recent years.

Don Hinkle - the public policy adviser for the Missouri Baptist Convention, which says it represents Missouri's largest non-Catholic denomination, with 550,000 members attending 1,950 churches - told the News Tribune the Johnson Amendment "is bad policy because it is unconstitutional. It is not about tax-breaks, but rather First Amendment rights being denied."

The U.S. Constitution's First Amendment says: "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances."

Hinkle said: "The 'free exercise' clause of the First Amendment guarantees that all Americans can fully exercise their faith and the government has no right to interfere."

The Johnson Amendment, he said, "denies Americans their freedom of speech."

But Brian Kaylor, associate director of the Baptist General Convention of Missouri, disagreed.

"The political action ban does not violate free speech rights," Kaylor said. "Every minister can still endorse a political candidate if they want. They can do so in their personal capacity. Or, if clergy believe they must engage in partisan politics from the pulpit, they still have the right to do so. They just cannot do so while keeping a tax-exempt status."

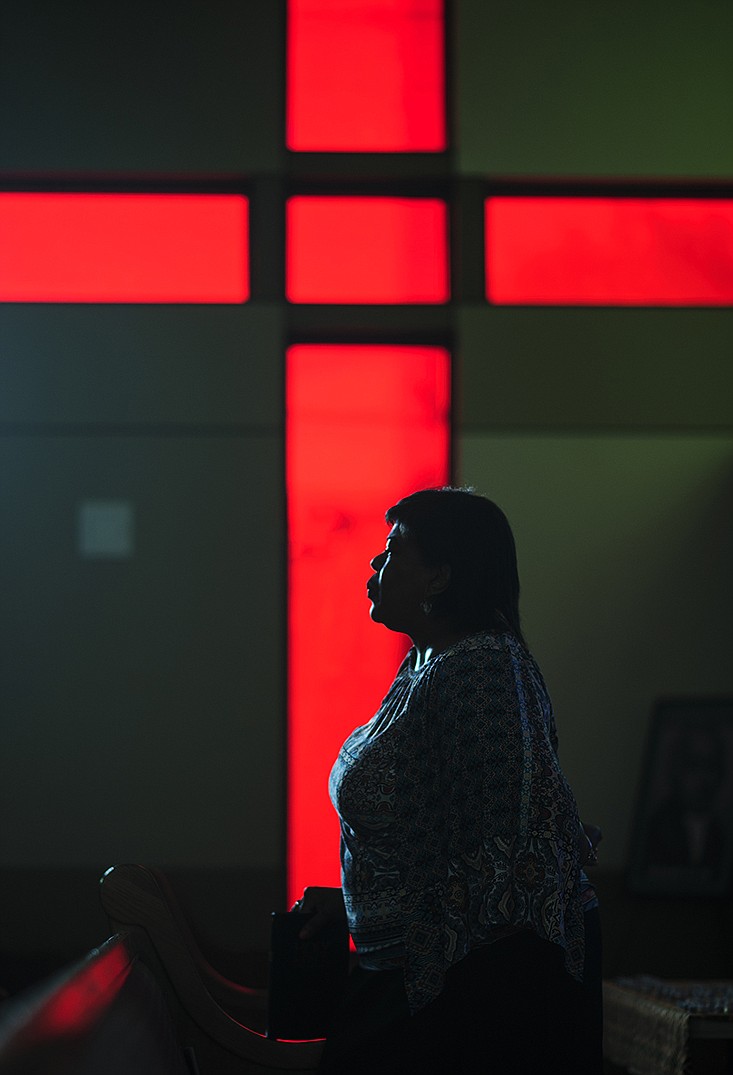

The Rev. Cassandra Gould, pastor of Jefferson City's Quinn Chapel A.M.E. Church and executive director of Missouri Faith Voices, also thinks the law "was and is a good piece of public policy (because) it keeps politicians from holding me or my colleagues hostage with political donations - or even a parishioner who's connected to a politician."

Gould noted the rule doesn't keep clergy or religious groups from talking about issues, and as the leader of Faith Voices, she is active in a number of social welfare campaigns.

For instance, Gould and the group back the proposed Clean Missouri constitutional amendment to "get money out of politics, in so many ways," and she connects that idea with the Johnson Amendment's keeping politics out of the religious message.

"I actually look at it as more of a protection than a restriction," Gould said.

Her congregation and Missouri Faith Voices are "very much involved in voter engagement" and helping people learn about issues, but "I don't want to tell people who to vote for. I believe that, as a prophetic preacher, it actually has the ability to weaken my voice," she said.

Gould also said the law helps clergy focus on religious precepts and not deliver political messages that do more to divide a congregation where people already hold different political philosophies, creating splits that may be impossible to heal.

Kaylor said the Johnson Amendment - which he prefers to call "the political action ban" - actually "is good for charities, good for houses of worship, good for our government and good for the American people (because) this rule treats all tax-exempt 501(c)(3) nonprofits equally," including houses of worship and numerous other charities.

But, if Congress were to change the law, Kaylor said, and "houses of worship are given a religious exception, it would actually create an unfair system where religious nonprofits would have special rights not given to all other similarly incorporated nonprofits. That would violate the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment."

Violating the restriction could result in the revocation of the organization's tax-exempt status and the imposition of taxes.

And that has happened.

In 1992, Georgetown University's Berkley Center for Religion, Peace and World Affairs reported a church group, Branch Ministries, "sponsored a series of advertisements in several major newspapers encouraging Christians not to vote for then-Gov. Bill Clinton," who was running for president against incumbent Republican George H.W. Bush and Independent candidate H. Ross Perot.

On the basis of those ads, the IRS revoked the church's tax exemption.

Branch Ministries appealed the revocation, arguing the IRS had violated both its right to the free exercise of religion guaranteed by the First Amendment and provisions of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act.

But the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia ruled against Branch Ministries.

On its website, the IRS reported: "The court rejected the plaintiff church's allegations that it was being selectively prosecuted because of its conservative views and that its First Amendment right to free speech was being infringed. The court wrote: 'The government has a compelling interest in maintaining the integrity of the tax system and in not subsidizing partisan political activity, and Section 501(c)(3) is the least restrictive means of accomplishing that purpose.'"

Active opposition

The Alliance Defending Freedom, known as the ADF, is a legal action center that represents mainly conservative Christians in battles over government regulations.

For several years, ADF has sponsored a "Pulpit Freedom Day," which "encourages pastors to exercise their constitutionally protected freedom to speak truth into every area of life from the pulpit," ADF explains on its website.

ADF has encouraged many pastors to record those sermons and send them to the IRS - but that has produced little effort to cancel those churches' tax-exempt status.

An Aug. 27, 2016, New York Times opinion piece written by author Kevin Baker explained: "The IRS, hobbled by years of budget cuts, has refused to rise to the bait. It is not believed to have opened any audits of churches for noncompliance under the Johnson Amendment since at least 2009, and all that ministers who send in recordings receive is a form letter thanking them for their interest."

Hawley told the News Tribune: "If the IRS tries to bring a suit against a Missouri church leader for speaking his or her mind, I will be happy to take up that case and defend the rights guaranteed to us all by the U.S. Constitution."

And the ADF said it "hopes to eventually go to court to have the Johnson Amendment struck down as unconstitutional for its regulation of sermons, which are protected by the First Amendment."

However, Kaylor said: "No one is stopping clergy from speaking out in any way. But there is no constitutional right to tax exemption. That is a special privilege our government gives to organizations."

Hawley disagreed.

"Free speech is free speech, free exercise of religion is free exercise of religion, regardless of whether a pastor is speaking from a pulpit, from the steps of a church, or from a living room," he explained. "The attempt of the left and of many members of the media to draw artificial legal distinctions that limit our First Amendment rights is a shameless attack on religious leaders for speaking their minds."

Hinkle said Congress "got it wrong" when it changed the tax-exempt part of the tax code 64 years ago.

"Those who say (the ban) is a trade-out for a tax exemption are terribly misinformed," Hinkle said. "It would make no sense for the government to tax churches because of the incalculable services they provide toward the common good. Government gladly provides tax-exemption to faiths. Imagine our society without hospitals, parochial schools, pregnancy resource centers, food pantries, homeless shelters, disaster relief support and a myriad of other services. These are services people of faith provide society and they do it better than the government ever could."

Kaylor countered: "I believe Congress struck the correct balance with the political activity ban. Clergy can still address any issue, including politically-contentious issues.

"This is not a ban on engaging in politics but on engaging in partisan politics with a tax-exempt nonprofit. Clergy and churches must have the right to address critical issues - and they do."

Kaylor added: "The idea that the ban was intended to be anti-religious liberty shows little understanding of the history behind it. The same session of Congress that passed the political activity ban also put 'under God' in the Pledge of Allegiance and expanded the clergy housing allowance. Those are hardly the actions of an anti-religious liberty Congress."

Opponents of a repeal worry churches and other organizations could become like political action committees, accepting donations for specific candidates without having to identify who those donors were.

Gould noted, under the current law, a church doesn't have to identify the people who give to it.

"I would not want my church to become a vehicle for 'dark money,'" she said.

If the law were changed, she added: "People could actually start funneling money (to churches) in a way that was tied to politics, that would be immoral."

Non-church nonprofits

Gould said the current law allows her to "call out bad policies and immoral policies - policies that I believe are oppressive, that come from both sides of the (political) aisle - without endorsing or opposing a particular candidate."

Kaylor emphasized the political activity ban affects all tax-exempt nonprofits - not just churches.

In March 2017, the Paul Clarke Nonprofit Resource Center in Fort Wayne, Indiana, wrote: "A repeal (of the Johnson Amendment) would blur the lines of what is a 501(c)(3) in terms of tax-deductions. Other nonprofits, like 501(c)(4), can engage in politics but cannot receive tax donations. It is possible that more entities and/or political groups would seek tax-deductible status to raise funds for political purposes and for potentially undisclosed donors.

"Also with the repeal, charities could ' lose the ability to receive tax-deductible donations ' and this would inhibit nonprofits from succeeding at their missions."