No one knows how long Missouri has until another earthquake rumbles from the New Madrid Seismic Zone, but the state's seismic preparedness officials are using whatever time there is to guide school districts in reinforcing as many school buildings as possible.

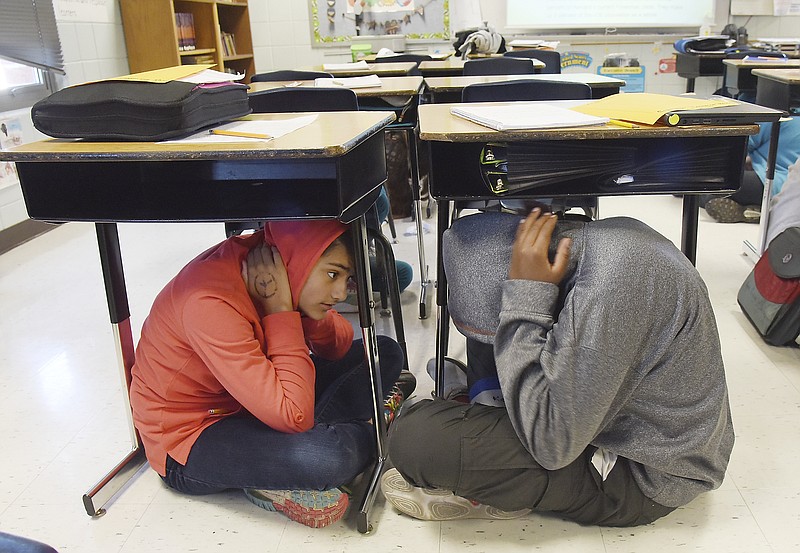

Schools and other institutions across Missouri took part Oct. 18 in the annual "Great Central U.S. Shake Out" earthquake drill - a reminder there's a 25-40 percent chance of a magnitude 6.0 or greater earthquake in any given 50-year time period in Missouri - and a 7-10 percent chance of a magnitude 7.0 or greater in any given 50-year time period.

Small quakes in the range of magnitude 1-2.5 happen all the time in Missouri's Bootheel area and across state lines in Arkansas and Tennessee.

On average, a damaging 6.0 or greater quake occurs about once every 80 years in the New Madrid Seismic Zone, according to the Missouri State Emergency Management Agency. The last such event was a magnitude 6.6 with an epicenter near Charleston in 1895.

Given that 123 years have passed since that temblor is not much cause for concern though, according to SEMA Earthquake Program Manager Jeff Briggs.

"You can't say you're overdue" for an earthquake, Briggs said.

He said to think of the probability of an earthquake striking like flipping a coin - an example in which the timing of past events has no bearing on the probability of future outcomes.

"One could happen tomorrow, or one could not happen for another 100 years," Briggs said.

The unpredictable upheavals of the ground in an earthquake zone are a given, but people have a certain amount of power over the extent and severity of the damage those tremors can cause - if communities use the time between quakes to prepare.

Briggs said all of the school buildings in Missouri that might be vulnerable to a quake won't be able to be examined, but the Missouri Seismic Safety Commission's free rapid visual screening program "is making a difference" by alerting school officials to possible structural issues, as well as giving them information that can be used to prioritize future investments in structural improvements.

The commission's screening program has used the services of volunteer assessors including architects, engineers and code enforcement professionals to look at more than 100 buildings in 12 districts over the past four years, Briggs said - most recently Maries County R-2.

The Blair Oaks R-2 district is also in the process of scheduling a seismic review of its buildings through the program.

Many school buildings in Missouri are of a design that's especially vulnerable to the forces of an earthquake's shaking - including parts of buildings at Maries County R-2, according to the district's preliminary evaluation report.

Older buildings constructed with bearing walls made of unreinforced masonry - usually bricks or hollow concrete blocks - will almost certainly be the first to be damaged whenever the next destructive quake strikes Missouri and its neighboring states to the east and south, according to a guide on improving schools' natural hazard safety, published last year by the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

Not all buildings with brick exteriors have bearing walls made of unreinforced masonry - it's about whether the bricks have to carry the structural load of the building's floors and roof without any other reinforcing material to support the walls.

Reinforced masonry walls have a grid of horizontal and vertical steel bars within the walls - in brick walls, the reinforcing bars are in a cavity between outer and inner stacks of bricks, and the space is filled in with grout - according to a unreinforced masonry risk-reduction document from FEMA.

The same document notes that based on the damage results of past U.S. earthquakes that exposed unreinforced masonry buildings to strong shaking, five out of every six unreinforced masonry buildings were damaged "to the extent that potentially lethal amounts of brickwork fell. One-fifth of those buildings either partially or completely collapsed."

Briggs said Missouri's Department of Elementary and Secondary Education told him the department does not keep track of how many schools have been constructed with unreinforced masonry.

"We do know that there are many older brick and unreinforced masonry buildings that are housing students throughout the New Madrid Seismic Zone," he said, adding many of schools the Missouri Seismic Safety Commission has structurally assessed were built with unreinforced masonry.

State law enacted in the 1990s requires all new construction, additions and alterations of public buildings meet a seismic code in areas of Missouri at risk from shaking equivalent to a VII on the Modified Mercalli scale - which measures a quake's intensity based upon its human and structural effects - from a magnitude 7.6 New Madrid earthquake.

There is no statewide seismic code standard, Briggs said, and a code for any particular building depends on where it is.

The state law does not apply to public buildings in which construction began or finished before Aug. 28, 1991, or to private structures with an area of less than 10,000 square feet - unless mandated by local ordinance.

Boone, Callaway, Cole and Osage counties are among the areas in Mid-Missouri at risk from shaking with an intensity equivalent to a VII on the Modified Mercalli scale from a 7.6 magnitude shock, according to SEMA.

A SEMA map shows some Mid-Missouri counties such as Maries and Gasconade a little closer to the Bootheel could experience less intensity - a level of VI - because more of an expected quake's intensity is projected to ripple northward through the Mississippi River's basin and then westward along the Missouri's from where the two rivers meet near St. Louis, mostly above the northern shore.

Intensity equivalent to a VI or VII on the Modified Mercalli scale is moderate - New Madrid, Pemiscot and Mississippi counties are projected in a magnitude 7.6 event to experience X out of a possible XII - but many people who experience level VII shaking probably would not think of it as moderate, per a description that accompanies SEMA's intensity map: "People have difficulty standing. Considerable damage in poorly built or badly designed buildings, adobe houses, old walls, spires and others. Damage is slight to moderate in well-built buildings. Numerous windows are broken. Weak chimneys break at roof lines. Cornices from towers and high buildings fall. Loose bricks fall from buildings. Heavy furniture is overturned and damaged. Some sand and gravel stream banks cave in."

Even in the lesser VI level of shaking, "Poorly built buildings are damaged slightly. Considerable quantities of dishes and glassware and some windows are broken. People have trouble walking. Pictures fall off walls. Objects fall from shelves. Plaster in walls might crack. Some furniture is overturned. Small bells in churches, chapels and schools ring."

That is what people in Boone, Callaway, Cole and Osage counties probably would experience in a magnitude 6.7 New Madrid earthquake.

The forces of acceleration in ground motion of even moderate shaking, though, multiplies the force of gravity acting upon unreinforced masonry walls in a structure and adds a burden of extra weight that can exceed the bricks' ability to carry it.

Unreinforced masonry walls are also vulnerable to quakes' flexing and shearing motions, and having the floor and roof of a building separate from the walls.

According to FEMA, two children in the United States have been killed at school in earthquakes over the past century - a number kept low because most damaging quakes so far have hit outside of school hours, though both students were killed by the collapse of unreinforced masonry walls. But even if damage to schools doesn't injure students, buildings that have to be closed for extensive repairs can deprive communities of emergency shelter space they might need.

Deb Hendricks, SEMA state volunteer coordinator, shared with Briggs that schools in Missouri are "among the locations pre-identified by the Red Cross (Missouri's shelter lead organization) for use as shelters in disasters," because school facilities are well-known and accessible to communities; have kitchen, bathroom and shower facilities, as well as lots of space for beds; and parents will go to schools if a disaster happens during a school day.

"This is a big part of why we do what we do," Briggs said of school buildings being "considered critical structures."

He said the seismic safety commission's screenings are not as detailed an assessment as an engineer could do with more time and details, but that is sometimes suggested that districts also do.

Maries County R-2's Superintendent Patrick Call said he didn't have any particular concerns that prompted him to request a screening of the district's buildings for seismic vulnerabilities, but the district wanted to know if there was anything of which they needed to be aware.

"You get to the point where you don't always notice little things. For districts, it's just nice to have another set of eyes," Call said.

Call gave Briggs permission to share the district's preliminary evaluation report from August with the News Tribune, and the report includes assessments of Maries County R-2's high school, middle school, elementary school, district office and bus maintenance buildings in Belle and Bland.

The more in-depth second of two structural reviews found two of the five parts of the high school, two of the four parts of the middle school, and two of the six parts of the elementary school scored as "life-safe" - estimated to have a 1 percent or less chance of collapse when shaken to the moderate level of ground motion expected at the schools' locations from a New Madrid quake. That's considered acceptable by the federal standards.

A 1973 addition to the district's middle school and the original 1959 gym and cafeteria section of the elementary school received the lowest ratings - estimated to have "roughly a 40 percent probability of collapse" if the buildings are exposed to the moderate level of shaking used in the assessment.

The rest of the areas of the district's school buildings scored somewhere in between - with two more areas of the elementary school rated to have a 10 percent probability of collapse in the estimated earthquake, "which is generally considered an unacceptable level of risk," according to the inspection report.

All of the most poorly rated areas in each of Maries County R-2's school buildings were constructed with unreinforced masonry. For other areas of the buildings, steel, light metal and wood framing, as well as prefabricated structures, were used; all scored better on the life-safe scale than the unreinforced masonry.

Call said the screeners didn't find anything "not within our ability to fix," but it's just a question of time and money in terms of what gets fixed and when. The district's maintenance director is working on prioritizing potential larger project needs identified by the seismic screening, he said.

The Maries County R-2 earthquake evaluation report also lists a few federal and state funding resources for schools to use to take steps to mitigate earthquake damage, but Briggs cautioned some are not always available, or only available after a disaster is declared.

There are also other seismic hazards for districts to think about beyond the core structural integrity of their buildings. Visual screenings like the one Maries County R-2 had can include looks at whether hallways would be clear of things that could block students' and staff's exit after an earthquake; whether there are unreinforced masonry chimneys or parapets that can collapse; whether light fixtures, suspended ceilings, bookcases and window air conditioning units can fall; and whether fuel tanks and connections for propane-fired equipment would be vulnerable to damage that could lead to spills, leaks and fires.

Briggs said the screening program gives free safety kits to districts that includes fasteners to secure furniture and other heavy items.

He said three more districts are scheduled to get visual screenings, and he hopes those inspections get done this year - with more schools on the waiting list behind them.

Blair Oaks R-2 Superintendent Jim Jones said his district doesn't yet have a date scheduled, but it too will get a seismic screening.

Jones said "there was no specific event or thing that said 'we need to do this.' We don't necessarily have a specific concern," but he added it's "an opportunity with zero cost."

He said last week that inspectors were in the process of gathering materials like floor plans.

Frank Underwood - Jefferson City Public Schools' director of facilities and transportation - said the consultants the district has used to evaluate tornado shelters have examined buildings for seismic vulnerabilities, but they haven't issued reports.

Underwood said he was interested in using the state's seismic safety commission's free program, though, once he was made aware of it - and he promptly called Briggs and said he got JCPS added to the list of districts to be scheduled for inspections.

"That to me, that's a no-brainer," Underwood said, adding he couldn't see any reason not to pursue "anything we can do to make our schools safer."

Doug Loveland - an ACI Boland Architects partner and architect of record on JCPS' two high school projects - said there's not a substantial seismic retrofit being done of Jefferson City High School in its renovation, but any new additions to the campus will have to meet seismic codes.

Loveland said structural engineering is not his expertise, so he also did not know what, if any, seismic safety features the building's old design might have already incorporated.

He referred to the DLR Group - also attached to the JCPS high school projects - for more specific structural questions, but the News Tribune was unable Friday to immediately receive a response from DLR Principal architect Amber Beverlin, whose expertise includes K-12 schools.

The News Tribune also attempted to contact Cary Gampher, The Architects Alliance's principal architect, but he was unavailable.

"I don't know that there's a hard and fast answer to that," Briggs said of how and when a school district on the fringes of the most at-risk areas for a New Madrid quake should prioritize risks in its buildings that may be identified through screenings.

"You might be able to undertake some lower cost improvements in Mid-Missouri that might be all you need to be seismically resilient," he said - whereas in a place like Sikeston, more costly improvements might be needed because the risk of major damage is greater.

"I would say anywhere in the seismic zone, history says one of these days we're going to have a big one," so anything affordable that can be done is helpful to know about in advance, Briggs said.

School districts interested in more information on the rapid visual screening program can contact Jeff Briggs at 573-526-9232 or at [email protected].