MEXICO CITY (AP) - The earthquake struck in seconds, but three years later, restorers still face a monumental task: about half of the 2,340 colonial-era buildings and churches damaged in the 2017 Mexico quake still need to be repaired, restored or partially rebuilt.

It is a titanic challenge: Crumbling old stone and lime mortar walls and domes, without an ounce of cement or rebar, have to be built back with the same ancient materials.

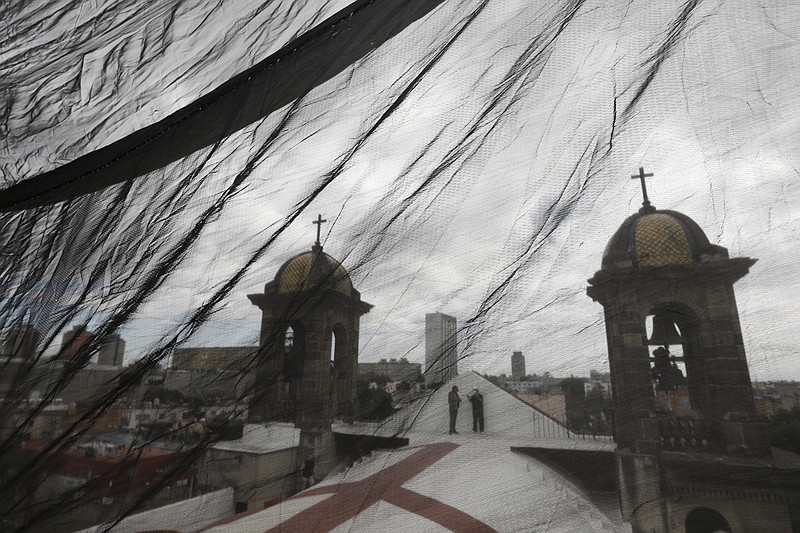

But that doesn't mean the work is primitive. At the Nuestra Seora de Los Angeles church near downtown Mexico City, the restoration work has a space-age feel: Towering curved metal support structures are delicately lowered into place by huge cranes, to support the half-collapsed dome of the church. Meanwhile, the other, standing half of the 100-ton dome looms 80 feet above workers.

"There is always a sensation of risk being in there, of course, because you sense that pieces could come falling down at any time," said Antonio Mondragn, the architect at the National Institute of Anthropology and History who leads the restoration effort. "Any material that comes flying down from 25 yards would be very dangerous. There is always a risk, and we know we can't stay inside very long."

Mondragn has gained a respect for the old church - a chapel built in the late 1500s stood here, of which only a portion of one wall remains, while the collapsed dome was built between 1740-1884 - calling it "noble." The dome didn't collapse at the moment of the quake, but rather five days later, leaving time to get people and precious objects out.

It is so dangerous to stand beneath the remains of the dome that the tons of steel structures are made off-site and then gingerly lowered into the crater at the center where the dome once stood; the steel beams simultaneously brace the remaining walls of the cupula, provide a work platform just under the dome and the arch over the top, to provide trusses for a temporary metal roof.

The experts working on projects like this across Mexico face some of the same issues confronting restorers everywhere, like France's re-building of the Notre Dame Cathedral. Are the materials and craftsmen's skills of centuries ago still available? How can you explain delays to impatient modern citizens for whom construction is something that is done in weeks or months?

"It is true that some of the finer, more specialized knowledge of these (construction) crafts has been lost. This work is still being done, perhaps more clumsily, but the crafts remain and people know how to work with these materials," Mondragn said, referring to the quarry stone and super-light "tezontle" volcanic stone used to build the original dome. But with quarries near the city depleted - or filled in to create housing - Mondragn said "in effect, it gets harder every day to find good material."

Initially, restorers thought they would have to dismantle what remained of the dome and re-assemble it piece by piece, Mondragn said. But they realized the cause of the collapse had been an enormously heavy central cupola that stood atop the dome and which had been leaning out of level because the church was unevenly sinking into Mexico City's notoriously swampy soil. So the collapsed part could be rebuilt and mated with the remaining structure.

The $2 million restoration effort at Nuestra Seora de los Angeles will take at least two years more; impatient residents often ask experts why it is taking so long. To date, about 1,100 of the 2,340 damaged structures have been restored.