We hear little about history in Central Missouri before the Spaniards, French and early explorers. But the stories of their exploits cover only a small sliver of time in the long history of humans occupying these lands.

Early humans crossed the Bering Strait from Asia into North America as early as 30,000 B.C. It is now believed some also came by boat. The earliest evidence of humans in Missouri is estimated at 12,000 B.C. in what archaeologists call the Paleo-Indian culture. At Mastodon State Park near Imperial, Missouri, archaeologists found human lithic (stone) artifacts and mastodon bones together, providing the first evidence in Eastern North America of the co-existence of humans and the now-extinct mammal. Mastodons became extinct by about 10,000 B.C.

The traces of ancient Indian cultures in Mid-Missouri are abundant, yet it literally requires some "digging" to find them. Remnants of Indian occupation sites can be found on practically every blufftop along the Missouri River in Cole County. Jefferson City's public buildings now occupy some of these bluff tops.

Occupation sites can also be found in the bottoms and along the banks of the Moreau and Osage rivers and Grays and Wears creeks.

There are more than 37,000 known sites in Missouri, according to the State Historic Preservation Office. These sites probably represent only a fraction of the total. While a number is not available for Cole County, Boone County reportedly has 1,300 known sites. The nearby archaeology departments of University of Missouri and Lincoln University may have something to do with this. When you look for them, you will find them.

In Cole County, lithic artifacts have been found dating back to the Dalton period, a transition phase between Paleo-Indian and Archaic cultures going back as far as 8,000-7,000 B.C.

In Goodspeed's 1889 Cole County history, Gen. James Minor is quoted saying, "The capitol is built on one such mound and in its excavation the workmen exposed a great number of bones and pottery." He added that Judge Arnold Krekel informed him "a mound was excavated on his beautiful place in our city in which were found the moldering skeleton of a large man and three or four smaller bodies." Judge Krekel's home still stands on Cliff Street just west of the State Archives.

There were mounds also reported on the site of Heisinger Bluffs, Capitol Region Medical Center and the DNR office building on Riverside Drive.

One account in the 1870s noted a large mortuary mound was found at Cole Junction near the mouth of Gray's Creek. The landowner built a cistern through the center of it. Around this same time, a farmer near the mouth of the Moreau River built his farmhouse next to a very large mound, but "finding this mound shut off the air from his house, he had it dug down, using the earth taken from it to terrace his dooryard."

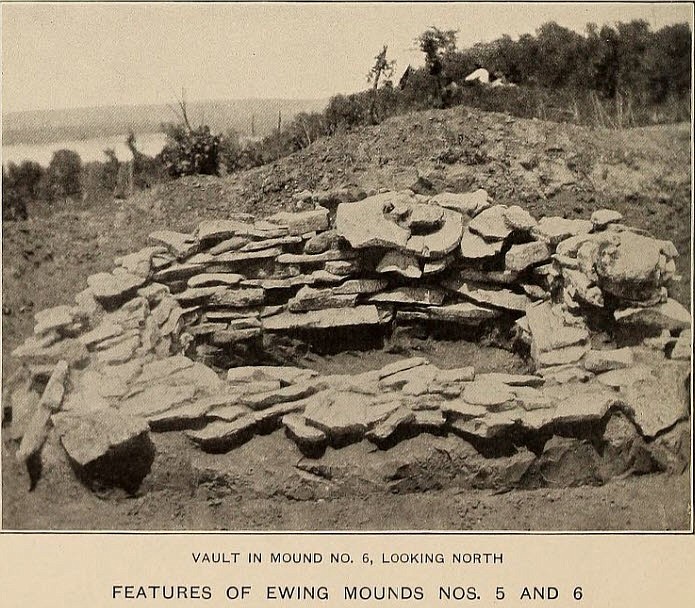

The land between the mouth of the Moreau River and the Algoa Reformatory has been intensely surveyed. It is often referred to as the Ewing Farm or Algoa Site. Here, as many as 11 mortuary mounds and 13 pits have been reported in the span of about one mile. Many of the mounds had been plundered long before.

Today, it is a Class D felony to disturb burial mounds, besides being very disrespectful. Unfortunately, this legal protection was not in place before many sites were destroyed.

In 1977, Craig Sturdevant, a professor of archaeology at Lincoln University at the time, led a team to survey and salvage the Algoa Site under a contract with the Department of Natural Resources. The study covered 770 acres. Carbon dating of fauna and flora at the site revealed humans have occupied this site as far back as the Archaic period, around 7,000 BC. Some lithic artifacts (points and tools) found in the area extend back to the Dalton culture, 8,000 B.C. However, Sturdevant's team found most of the artifacts at the Algoa site were dated to the late Woodland culture, 500-900 AD. Oddly, his team found nothing dating to the early and middle Woodland, from about 1,000 BC to 500 AD.

The Mississippian culture followed the late Woodland, around 700 AD to 1,500, but there is little evidence that Indians of this time period occupied Cole County. These Indians were the mound builders. The Cahokia Mounds in eastern Illinois are of this period.

After 1,600 AD, the Osage Indian tribe dominated a large swath of central and southern Missouri. It may come as a surprise that while Cole County was Osage territory there is no evidence of a village here associated with them. There was an apparent hiatus in human occupation from about 900 to about 1,400 AD in this area. Archaeologists have not been able to establish with certainty the connection between the mounds in Cole County and the Osage tribe that came later.

Jenny Smith is a retired chemist with the Highway Patrol Crime Lab and former editor of the Historic City of Jefferson's Yesterday and Today newsletter.