Instructors at a Jefferson City school are encouraged by its method for tracking and responding to student progress.

Capital City High School offers data teams -- groups of teachers in the same department that meet at the beginning and end of each unit of study to discuss student results on a pre-test and a post-test on the unit material. They make a plan on how to get students where they need to be academically.

Data teams at CCHS are mainly used in EOC-tested areas, which are Algebra I, Biology, Government and English II. Other schools have their own different versions of data teams, but for CCHS, English II, Biology and Algebra I data teams are in their third year, and Government data teams are in their second.

Emily Vallandingham, associate principal of curriculum and instruction at Capital City High School, said each unit assessment is built around priority standards in the curriculum. Units range in length from three to six weeks, depending on the content for an average of four units each semester.

"The teachers, they know at the end of this unit that the kids are going to have to be able to take and pass this test over these priority standards, but they don't want to just teach the lessons and hope that the kids all get it. They want to be responsive to student needs and student data and plan their instruction accordingly," she said.

Pre-test data

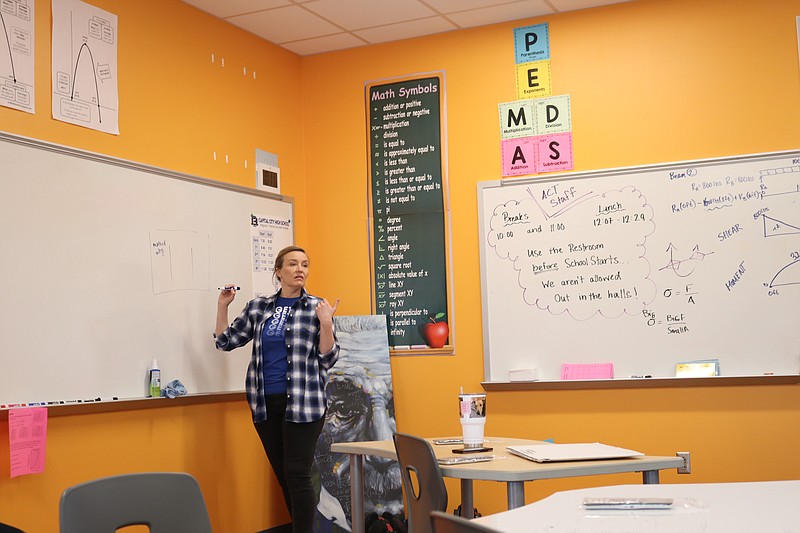

In the math department, Alex Miriani, Lesley Woinicz, Lauren Gilbert and Tammy Peterson discussed pre-testing over graphing systems of equations and inequalities. The pre-assessment quiz showed 62 percent of children at proficient, 13 percent near proficient and 25 percent below basic.

Miriani said the goal is to move students up one level, although moving students from red to green would be ideal.

The team talked about strengths and weaknesses they saw in students' answers -- what they forgot, what concepts seemed to be difficult and what they definitely understood.

Then they came up with a strategy.

The group ended up setting a goal of 82 percent at proficient, a 20-point increase.

"This is what I definitely want to do next week, is a self-reported grade over the inequality parabola, where they have to go through and award themselves points for rearranging, graphing the line, dashing and shading," Miriani said. The other teachers agreed, saying it would help the students understand where they were missing points.

Woinicz drew a worksheet she was envisioning on the board following the cognitive task analysis strategy. The sheet would ask the students to solve problems and explain why that solution method works best.

"And all those strategies really focus on having those conversations and that self-awareness of what they're supposed to be doing, it's not the teacher telling you, 'Hey, you should be doing this.' It's them looking at a problem and thinking, 'Okay, I should be doing this, and this is what I need to do ... or this is how I missed points, or this is what I should be doing to get better,'" Miriani said.

Post-test data

After teachers set a goal, they teach using the strategies they planned for, then compare the post-test data with the beginning data to see if they met their goal.

In the English department, teachers Brian Knight, McKenzie Bennett and Todd Beaulieu discussed post-testing for a unit in which students had to write an email persuading the school board to make a change. Students chose topics such as a free hour for school lunch, a four-day school week, or offering sign language classes.

Bennett said that after the pandemic and in an age with ready access to technology, students' reading and writing "stamina" is suffering. Bennett said they tried to build students' writing stamina by breaking up essays into portions and writing each separately.

The team chose the strategies of "self-grading," where students evaluate their own work and collaborative research, where they were assigned a topic and position for which they would gather evidence.

The team met its goal for student improvement on tests, reaching 86 percent of students scoring 70 percent or higher. It had also set a secondary goal for at least 75 percent of students to turn in a completed assignment, since incomplete assignments had been a problem. Ninety-two percent did, meaning that goal was also achieved.

When students don't meet the goal, teachers make a plan for how they can "spiral" the content into another unit to make sure students get it.

"And even when we have a unit where we feel like we didn't get the data success, we still have that professional growth, and that collaborative growth, and that reflective growth, that no unit is a failure because at the end of the day, we're still learning from what we did, and we're working together to figure out how to do better in the future," Vallandingham said.

Sometimes, data teams have to come to terms with a strategy that flops.

Vallandingham said for one unit the math data team had created a plan to address student growth through jigsawing, an instructional strategy that has students teach each other a portion of the content through verbal presentations.

The teachers saw students master the content during the learning portion, but when the test rolled around, the scores were disappointing. The team realized it had focused so much on that one strategy that their students didn't know how to show their knowledge of the subject in writing -- a lesson the team carried into future units.

Results

Generally, Vallandingham said the method is effective in increasing scores from pre to post-tests.

That doesn't mean the teams will always hit their goals.

"Usually the attitude is, well, let's shoot for the moon. Why would we say we only want 70 when we could say we want 75? And so sometimes, they will show huge strides, but they fall short of their goal. But it's in the name of, we don't want to set a low bar," she said.

Vallandingham said data teams have proved fruitful for the school and for individual teachers.

When she came in as a new principal years ago, she was passionate about data teams.

"I remember I called them (teachers) all in, and we had a training session, and there wasn't a whole lot of talk in that meeting, but they all said, 'Okay, fine,'" Vallandingham said. "Well, after several months of it, I had a math teacher say, 'I'm going to be honest. When you had that training in August, I was not real happy about this. I was thinking, this is extra work, this is going to add to my plate.' And she said, and she will say to this day, 'I won't be able to ever teach again without this process.'"

"She figured out it wasn't more on her plate. It was, this is your plate. This is the work that we do," she said.