At 47, Alex Robertson, of St. Louis, has spent almost half his life in prison -- 23 years.

Convicted of second-degree murder, robbery and assault, he faces two life sentences.

He knows he'll never leave prison.

However, he said he's changed over the years in prison.

"I had a completely different perception. I was angry and bitter," Robertson said during an interview inside Jefferson City Correctional Center (JCCC). "All I cared about was making myself feel justified in what I did."

And he had no feelings toward others.

"My victims weren't humans. People in these prisons weren't humans," he said.

Robertson decided it was time to do something different.

His path led him to Freedom on the Inside, a program in the Missouri Department of Corrections that is transforming offenders into ministers.

Although the first of its students won't graduate for two more years, Freedom on the Inside is already receiving accolades as a life-changing effort organizers hope will, much like a wave, spread through the corrections system.

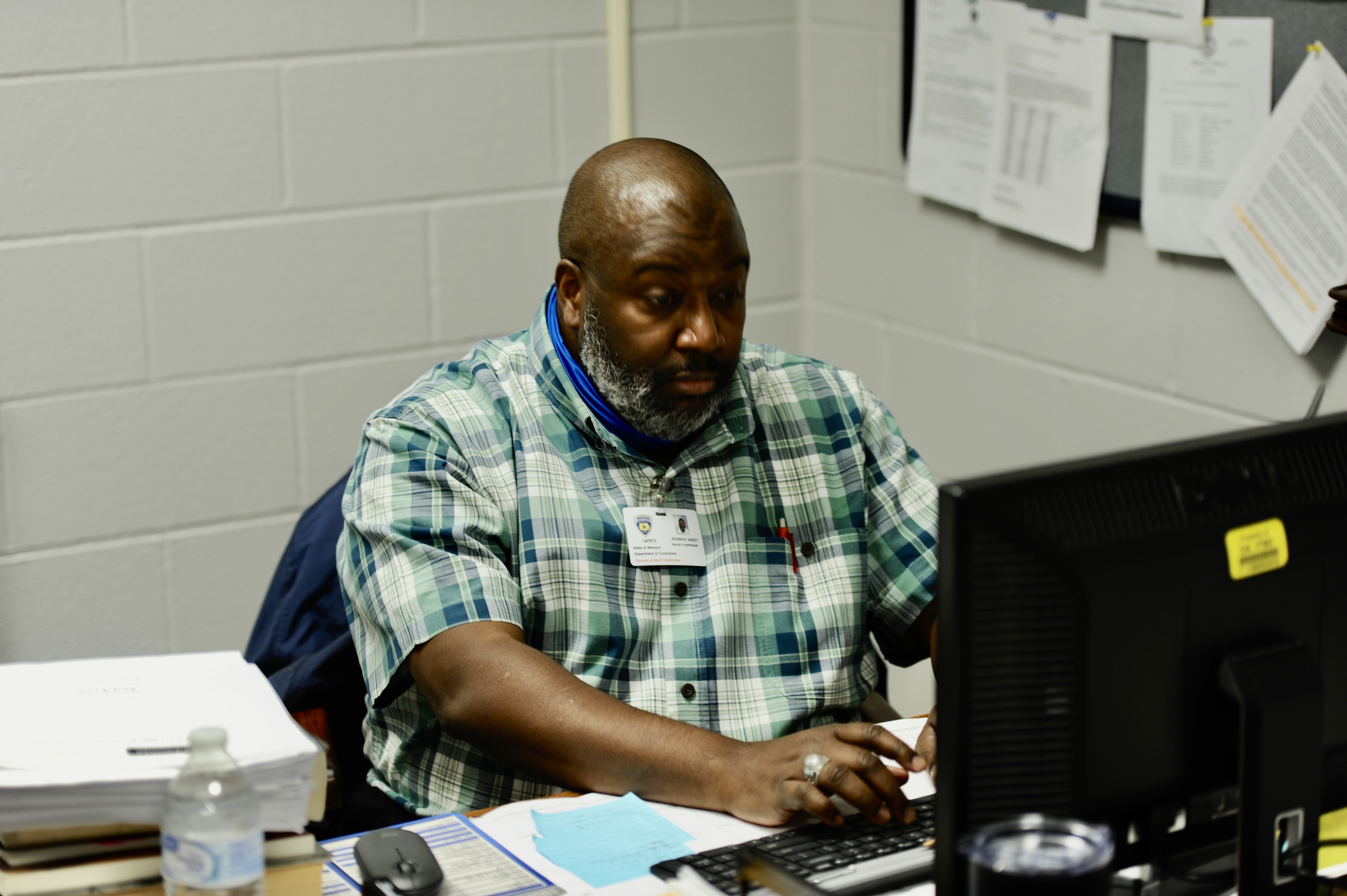

Freedom on the Inside is a Christian studies bachelor's degree program DOC is offering in partnership with Hannibal-LaGrange University (HLGU), although not all the students are Christians, said Rodrick Sweet, the program site director.

Freedom on the Inside is modeled after an initiative that began at Angola (the Louisiana State Penitentiary).

It was created because the prison's warden realized offenders needed moral rehabilitation, Sweet said. Then-Angola Warden Burl Cain reached out to a Baptist Seminary to help with the effort. The seminary began an extension program in what was once considered "America's bloodiest prison." Prisoners became ministers inside the walls.

Before long, wardens in other prisons asked Cain to send seminary graduates to their prisons, where they might help change cultures.

Texas soon began a similar program. Now Missouri.

The plan is to bring in candidates from prisons across the state, train them, then return them to the prisons where they were originally housed.

Missouri is starting small.

Last year, 20 students (all from within JCCC, including Robertson) joined the inaugural class of students for Freedom on the Inside.

The second class, which started this year, pulled students from prisons across Missouri.

Like several other members of the first two classes, Robertson undertook the "Impact of Crimes on Victims" class in 2009, and later joined the Intensive Therapeutic Community.

"I had a spiritual awakening. I was a pseudo-Muslim. I looked like one, but I wasn't acting like one," Robertson said. "I was looking for sobriety, serenity and peace of mind. It comes from faith in God."

Impact of Crimes on Victims classes are part of Restorative Justice, DOC spokeswoman Karen Pojmann said.

"The 40-hour curriculum gives crime victims a safe place to talk about how crime has affected their lives, and offender-students gain a better understanding of the long-term impact of criminal behaviors, helping them to develop empathy for and sensitivity toward crime victims and avoid future victimization," Pojmann said. "Classes cover multiple topics: victimization; property crimes; child and elder abuse; domestic violence; assault; sexual assault; drunk driving; robbery; drugs; and homicide."

Intensive Therapeutic Community is a voluntary, peer-driven, structured community within a housing unit wherein participants commit to long-term change in regard to criminal thinking, substance-use and destructive behavior patterns, Pojmann said. They work on anger management, self-esteem, sobriety and other key areas while holding one another accountable for their attitudes and behaviors. Classes and support groups are facilitated by offenders who have graduated from the program, or "elders," who reinforce structure, counsel their peers and address crises.

"I have to take the ups with the downs, the goods with the bads," Robertson said.

This year, the state brought in 20 students from other sites. Corrections has agreed to transfer students to JCCC, where they are to remain until they complete the four-year program.

Offenders in the program all face life sentences or aren't likely to leave prison because their sentences are so long. Of the first 40 students, officials kicked two out of the program for disciplinary reasons and removed one because laws regarding his sentence changed, Sweet said. He'll soon be released from prison.

Offenders are deeply vetted before being accepted into the program.

They must fill out a five-page application, which they give to their prison chaplain. The chaplain approves it and gives it to Sweet, who shares it with the warden and major at JCCC.

"We rely heavily on recommendations from their chaplain and supervisor, if they work; and officers they know," he said. "Each unit signs off on the application."

Each also is looking for something within the offender.

"I'm looking for someone who wants to serve the prison," Sweet said. "Wants a culture change -- Who'll be working offender-to-offender, offender-to-staff, staff-to-offender."

The goal is to return offenders, including two Muslims and an atheist, to the prisons where they originated, where they might act as "field ministers," he said. The field is the prison where they are housed.

"They will be under the supervision of the prison chaplain. They'll offer classes, hospice care and other services," Sweet said. "Our Muslim students are focused on hospice, and trying to get guys to renounce gang affiliations."

Mike Lester, 42, of Arkansas, convicted in 2000 of rape, robbery, burglary, sodomy and armed criminal action, is serving life plus 250 years.

He studied a Bible verse as he spoke last week.

Lester said he believes in God, but never practiced what he believed. For the past few years, he's been trying to grow closer to God.

"It was time for me to start accepting what God had for me," Lester said. "A man asked if I'd like to become a missionary in prison. I will always be studying the word of God. I will work to bring people to Christ, wherever he sends me."

Eddie Boyd, 62, accepts that he'll likely die in prison. He received a sentence of 25 years for his latest crimes, first-degree assault and domestic abuse. His latest incarceration is about his eighth as an adult, Boyd said.

"They would refer to me as a career criminal. I was locked up for a juvenile homicide," he said. "I've spent most of my life in the Department of Corrections."

Over the years, he said, he abandoned God.

"This," he said holding up a Bible, "brought me back."

News Tribune/Joe Gamm

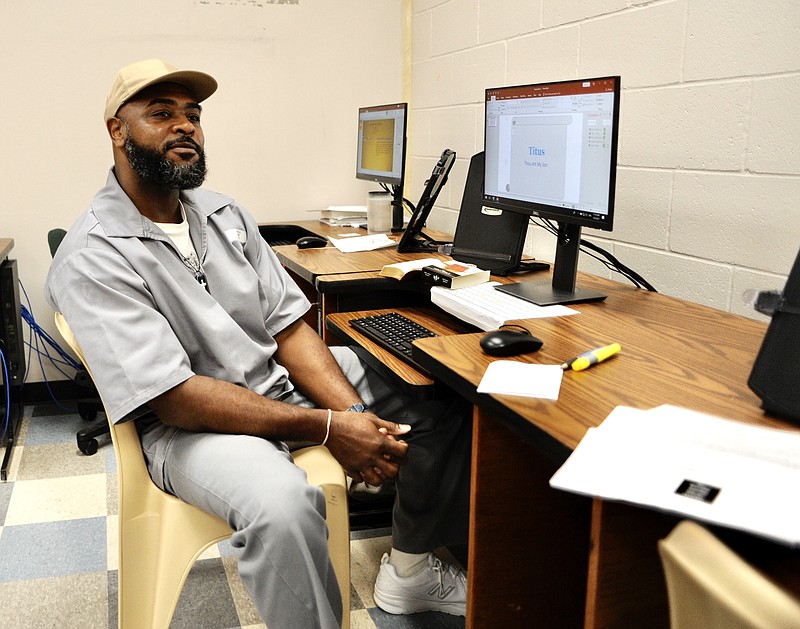

Quentin Jones, 42, (left) and Alex Robertson, 47, said they wish to build on lessons learned in Freedom on the Inside, a program intended to let offenders earn degrees in ministry. Students who complete the programs are expected to act as field ministers (within the prisons where they are held).

News Tribune/Joe Gamm

Quentin Jones, 42, (left) and Alex Robertson, 47, said they wish to build on lessons learned in Freedom on the Inside, a program intended to let offenders earn degrees in ministry. Students who complete the programs are expected to act as field ministers (within the prisons where they are held).