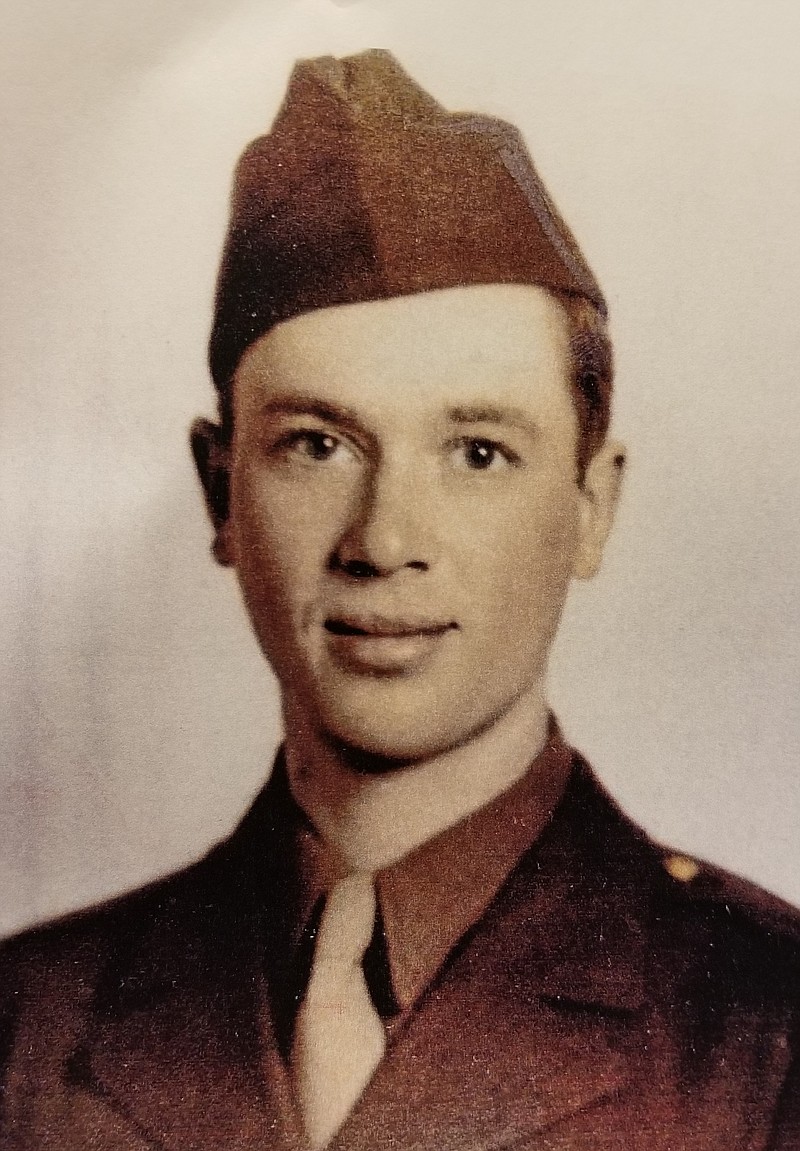

Editor’s note: Iowa veteran Herb Basener was recently interviewed about his WWII service while visiting family near Lohman.

Herb Basener’s father served in the German naval forces prior to the outbreak of World War I. Realizing the conflict brewing in his country, he pulled up his roots and immigrated to the United States where, more than two decades later, his own son, a first-generation citizen, would go on to volunteer for military service during the Second World War.

As Basener explained, he grew up on a sheep ranch in Montana, but in 1935, shortly after turning 14 years old, his family moved to a farm near the small community of Meservey, Iowa.

“After I graduated high school in 1939, I spent a two winters attending classes at Iowa State University in Ames taking herdsman courses,” he explained. “When I wasn’t in school, I was back home working on the farm until I decided to join the Army Air Forces before I was drafted,” he chuckled.

Inducted into military service at Camp Dodge, Iowa, on Nov. 3, 1942, the draftee was sent to Coffeyville Air Base in Kansas, where he completed his basic training and learned the meaning of “KP” (kitchen police) duty.

“They had me working in the kitchen and I knew there had to be something better, so I asked the mess sergeant if he needed another cook, and he did,” Basener said. “I began working with two civilian cooks and became good enough that I began serving the midnight meal to the pilots in training,” he added.

Despite any culinary skills the young soldier may have developed, he was soon sent to Keesler Field, Mississippi, for 19 weeks of training to become an airplane mechanic for the Consolidated B-24 Liberator — a heavy bomber used in World War II.

Basener remarked, “If you look at the instrument panel of a four-engine bomber, you would wonder how anybody could know if everything was working. I wasn’t sure if I was learning or remembering enough to be a mechanic, but the instructor said I would get a passing grade.”

In early summer of 1943, with his training in Mississippi completed, he traveled to Ypsilanti, Michigan, for an additional four weeks of aircraft mechanic training focused on the hydraulic systems of the B-24s. From there, he was sent to Laredo, Texas, for six weeks of aerial gunnery school, the final component of his pre-deployment training.

“First we used a shotgun to shoot at clay pigeons and then began shooting moving targets with a .30-caliber,” he said. “Then we learned to assemble and disassemble a .50-caliber and shot at a sock target that was towed behind an airplane.”

From there, he was sent to an personnel assembly site in Salt Lake City, Utah, and assigned to a flight crew consisting of a pilot, co-pilot, navigator, several gunners and a flight engineer. Receiving the designation of flight engineer, Basener was stationed aboard the B-24 in a section behind the pilots and under the top turret gunner.

“During my first training flight at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base near Tucson, I got so ill and reported it after we got back,” the former airman said. “I was told it wouldn’t keep me from flying but after that I wasn’t scheduled for another flight. Eventually,” he added, “a crew chief asked me to be his assistant, and I accepted.”

Assigned to the 834th Bombardment Squadron of the 486th Bombardment Group, in April 1944, he deployed to Station 174 in near Sudbury, England, where he helped maintain the B-24s that were conducting bombing missions against German targets.

“The B-24s were replaced by B-17s (‘Flying Fortress’ — a heavy bomber) later that year, and I was asked to be a crew chief on one of these planes,” Basener recalled. “When the planes returned from a mission, the pilot would report any mechanical problems, and I would make sure they were repaired and the plane was ready to fly the next day.”

He further noted, “After an engine was replaced, the pilot would ask one of the mechanics, usually the crew chief, to fly along on a short flight to break in the new engine and make sure it was working correctly.”

The routine of his duties were occasionally interrupted by air raid sirens from the threats of V-2 rockets (known as “buzz bombs”) launched by German forces. Another challenging circumstance came in the winter of 1945, when he spent several weeks in the hospital because of pneumonia.

Shortly before the end of the war, Basener recalled, approximately 400 of their B-17s were converted to transport food to the liberated areas. Following the surrender of Germany in early May 1945, he joined his fellow airmen of the 486th Bomb Group in preparing the aircraft for return to the United States.

His 35 months of military service came to an end when he received his discharge from Santa Ana Air Base in California in October 1945. Returning home, he married the former Frances Wendel (a high school classmate), raised five children and made a living by farming for 50 years, retiring at the age of 75.

For the veteran, his brief period of service bestowed upon him the sense of responsibility that comes from knowing your actions might be the difference between life and death for other individuals.

“The military was a time in my life that showed how important it was to learn what you were supposed to do and to do it correctly,” Basener said. “When you take care of a plane carrying 10 men into a hazardous situation, you feel accountable for their lives and want to do your job right so they could return home.”

“I always thought I was responsible for ensuring my plane was mechanically sound so they could complete their missions safely.”

Jeremy P. Ämick writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.