INDIANAPOLIS (AP) — Neither woman could bring themselves to watch the video of George Floyd’s final moments, his neck pinned under a Minneapolis police officer’s knee.

However, as their city grieved, Leesa Kelly and Kenda Zellner- Smith found much-needed comfort in the messages of anguish and hope that appeared on boarded-up windows as residents turned miles of plywood into canvases. Now, they’re working to save those murals before they vanish.

“These walls speak,” said Zellner-Smith, who said she was too numb to cry after Floyd’s killing. “They’re the expressions of communities. We want these feelings, hopes, calls to action to live on.”

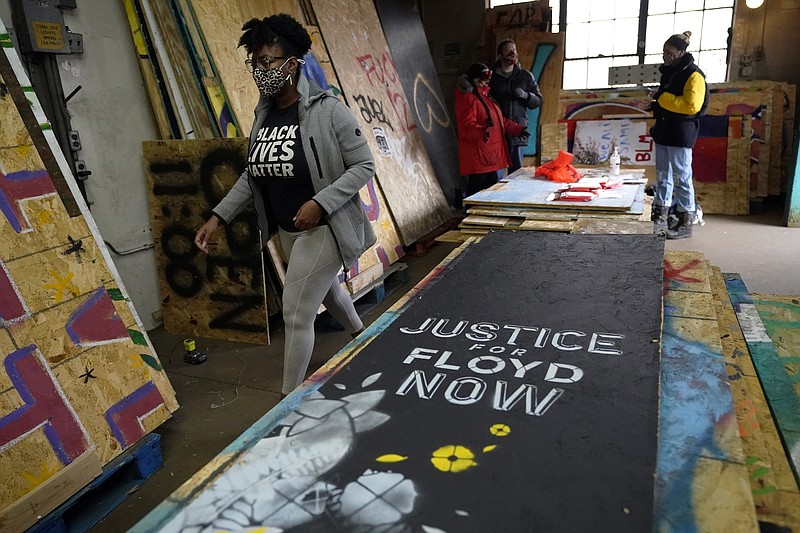

Together, the two Black women formed Save the Boards to Memorialize the Movement, part of a push to preserve the ephemeral expressions of anger and pain born of outrage over racial injustice that triggered weeks of protests across the country.

Some artists began painting intricate murals, but many spray-painted raw messages of anguish. Zellner-Smith started with the simple pieces.

“Some of these boards aren’t pretty,” she said. “There is collective pain and grief in each board, and each one tells a different aspect of this story. And now we get to tell that story to everyone.”

One is the word “MAMA” scrawled hastily onto the side of an abandoned Walmart. The word was among Floyd’s last. Now it’s part of a database of protest art called the Urban Art Mapping George Floyd and Anti-Racist Street Art database.

“The art was changing quickly, and these raw, immediate responses were being erased and painted over,” said Todd Lawrence, an associate professor of English at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minnesota, and one of the database’s creators. “We want people to see the full range of responses, the complexity, the multitude of voices.”

Lawrence and art history professor Heather Shirey were part of a research team already documenting street art. When the streets of countless cities became temporary galleries after Floyd’s death, they set out to capture the art before it disappeared.

Although many of the 1,600 artworks in the crowdsourced database come from Minneapolis, Shirey said they hope to expand to pieces from around the world.

“Oppression and racial violence is unfortunately universal, so art is responding to it around the world,” she said.

Similar work is going on across the country as groups take measures to keep the art alive.

In New York City, the Soho Broadway Initiative worked with local arts groups to get permission for murals and provide artists with materials. As murals started coming down, the organization returned 22 artworks to artists and collected 20 more waiting to be returned.

In Indianapolis, organizer Malina Jeffers is unsure about the future of the Black Lives Matter street mural stretching across Indiana Avenue. The mural is wearing down from traffic, and with winter will come weather damage and snowplows.

But the mural will live on in prints and T-shirts created by the local Black artists behind the original mural. More than 1,000 shirts have been sold. Vinyl banners representing 24 other murals painted in the downtown area are displayed at the city’s Central Library.

“All of us know the mural won’t be there forever,” Jeffers said. “So we all wanted a piece of it to hold onto.”

For Seattle’s Black Lives Matter street mural, Mexican American artist Angelina Villalobos, aka 179, mixed her mother’s ashes into the bright green paint she used for the letter A. City workers scrubbed the mural from the asphalt after it began chipping, but one worker collected paint from each letter, which Villalobos plans to keep on her mother’s altar in the kitchen.

“I’m getting my mom back, but she’s been transformed,” she said. “It’s like … a time capsule of that mural experience and all the work and thought and pain that went into it.”

The original artists have repainted the mural, planning to touch it up again in five years.

Designers at the Seattle architecture and design firm GGLO are using a different approach to preserve protest art by creating an augmented reality art show that allows visitors to use smartphones to view works scattered around the city. The show includes a digital version of the “Right to Remain” poster by local artist Kreau, 3D graffiti honoring victims of police brutality and digital tears pouring over Seattle’s skyline.

Gargi Kadoo, a member of the design team, said much of the protest art around Seattle was removed. Street art has been erased in many other cities, including Tulsa, Oklahoma, where workers in October removed a Black Lives Matter painting at the site of the Tulsa Race Massacre where in 1921 a white mob attacked a prosperous African American district, killing an estimated 300 people. Other cities such as Indianapolis and New York City have seen their Black Lives Matter murals vandalized.

“This is our homage to the art that is gone,” she said. “It’s trying to keep the message alive virtually, in a form that no one can take down or hose off.”