The new governor comes from an agricultural background.

His home, Bolivar, is an agricultural town. He runs an agricultural business.

Gov. Mike Parson's history in the state's Legislature reflects those conservative, rural Missouri values.

The 62-year-old was born in Hickory County, where he was raised on a farm. After graduating from high school, he joined the U.S. Army and served two tours in the military police.

Back home, he joined the Polk County Sheriff's Office as an investigator and served under Sheriff Charlie Simmons, whom Bolivar Herald-Free Press Publisher Dave Berry described as a traditional, old-type sheriff.

It was 1983, and Simmons was about seven years into a 16-year run as sheriff. Hard work had made Simmons sheriff, and he expected his employees to meet his high standards. He was cut from a cloth woven in earlier days, Berry said.

Parson was up to the task.

"He never has been afraid of work," Berry said. "He's a common fella. Down to earth. What you see is what you get."

Parson knew what worked for his employer, Berry said. But he also anticipated change.

When it was time for Simmons to step away - in 1992 - voters elected Parson as sheriff. He became the first sheriff in the county who was as much administrator as lawman. Parson was "that first step" for Polk County, Berry said.

"Mike put good people under himself," he said. "He connected the office to county commissioners - built county relationships and got things done."

Being an effective sheriff opened the door to Parson becoming a state representative, Berry said.

He was elected to his first term serving the 133rd District in 2004 and was re-elected twice.

While a representative, Parson co-sponsored Missouri's Castle Doctrine, which states people who use lethal force against someone who illegally enters their home, car or even tent would be protected from criminal prosecution and civil lawsuits. Bill sponsors - among them former state Rep. Kenny Jones, R-California - said the bill presumed people had a reasonable fear of imminent peril, death or bodily harm if an intruder unlawfully or forcibly entered a dwelling or vehicle.

Jones said at the time that the legislation would protect people from civil suits. He added a lot of people might be afraid to defend themselves with lethal force for fear of being sued.

Jefferson City Police Chief Roger Schroeder and Cole County Prosecutor Mark Richardson were outspoken opponents of the legislation. They said at the time that homeowners could adequately defend themselves under Missouri's law as it stood at the time. Richardson said then that legal decisions surrounding people's lives needed to be made based on facts, not presumptions.

The men said that, under the proposed law, armed homeowners were to make decisions which in the past had been made by highly trained law enforcement officers. Laypeople don't have the training to make life-and-death decisions about when to draw a weapon and fire it at someone else, they argued.

Voters elected Parson to the Missouri Senate's 28th District Seat in 2010. He ran unopposed for re-election in 2014.

While in the Senate, Parson proposed the Missouri Farming Rights Amendment. Supporters of the amendment - which passed by a margin of 2,375 votes out of 997,000 cast - said it guaranteed all Missourians the right to farm and ranch. Opponents said it was a lightly veiled protection for mega-farms, and its provision preventing people from creating ballot initiatives concerning farming was unjust.

Parson had planned for a run at the governor's office in 2016. But he chose instead to run for lieutenant governor. He defeated his Democratic opponent, former U.S. Rep. Russ Carnahan, by receiving the most votes of any lieutenant governor in Missouri history. He won 110 of 114 counties.

Berry said Parson has a knack for working both sides of the political aisle.

"He's well thought of by his peers in both parties," he said. "I feel like he's like-minded with me. I feel like the best government comes from the middle."

Shortly after taking the lieutenant governor's office, Parson received complaints from medical officials about conditions at the St. Louis Veterans Home. An investigation into the home led to Parson issuing a report that documented five concerns.

The report stated the home prescribed anti-psychotic medications without informing primary care physicians, created complaint procedures that were designed to hide problems, lacked transparency for veterans and their families, was unable to hire and retain quality personnel, and had lost faith among veterans and their families.

Parson called for the director's ouster. Rolando Carter eventually was replaced by Theresia Metz.

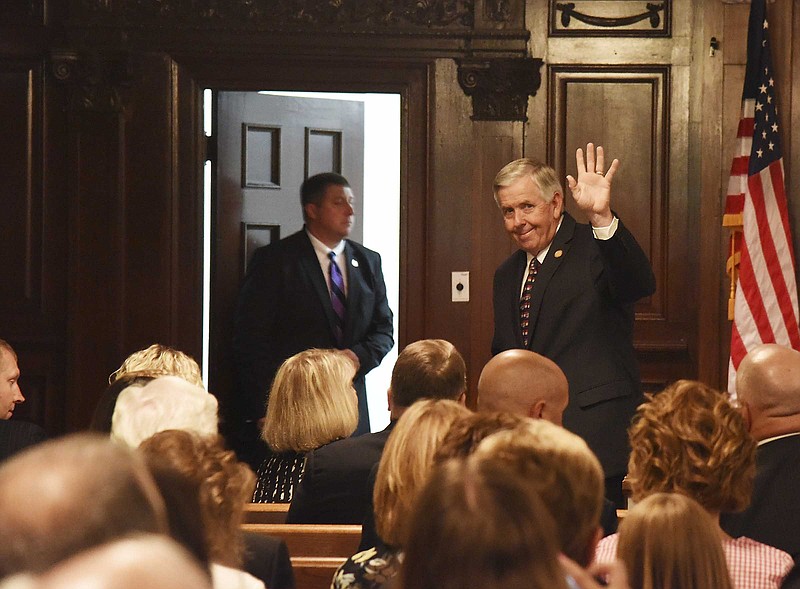

Now, just 18 months after his election as lieutenant governor, Parson finds himself in the state's executive chair.

Berry said he thinks Parson will work well with both parties. He said there are too many things being done that have the "fingerprints" of only one side or the other. Leadership changes, and things have the best opportunity to be lasting when both sides have their fingerprints on them, he said.