Now two weeks after Uber brought its 21st century transportation model to Springfield, local residents might be wondering whether ride-hailing services like it are en route to Jefferson City.

The technology may be straightforward, but the answer isn't.

Jefferson City's ordinance governing vehicles for hire never has been amended to accommodate transportation network companies (TNCs) like Uber, which allow customers to hail a ride using a smartphone app.

But, until last week, that didn't mean you couldn't hitch a ride - we checked.

The News Tribune successfully scheduled a trip last week using the Uber app. The driver, who called a few minutes after the request to confirm the pickup location, arrived in a clean, roomy SUV to bus two passengers 6 miles from the News Tribune's downtown office to a grocery store on the west end of town for a fee of $12.32.

It happened to be the driver's first trip with Uber. A Jefferson City resident, the driver planned to see how much business could be had here before exploring Columbia, which has an established Uber presence.

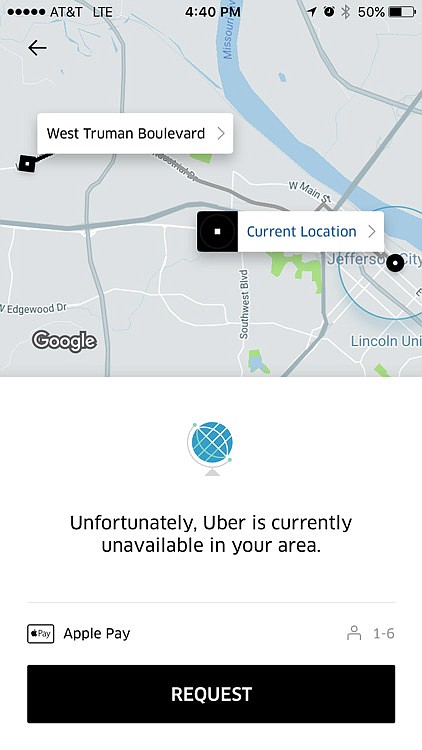

The next day, after the News Tribune had contacted a company representative, a similar attempt prompted a new message in the app: "Unfortunately, Uber is currently unavailable in your area."

The Uber representative did not respond to the News Tribune's requests for comment.

Jefferson City's code specifies it is illegal for any person, corporation or partnership to operate a vehicle-for-hire business without a permit. The probable penalty for violating the code would be $500 a day, City Attorney Ryan Moehlman told the News Tribune.

Diantha Lupardus, an Uber driver in Columbia who started the job while commuting from Jefferson City, said while she never took one herself, the app made Jefferson City rides available.

"You can actually turn it on, and if someone does turn their app on in Jeff and you're there, it will let you originate a ride there. But you're not supposed to," Lupardus said, noting she never noticed much volume of customers looking for rides in Jefferson City, likely because it wasn't publicized that it was available.

Jefferson City officials discussed amending the city's vehicle-for-hire regulations to include ride-hailing services like Uber during council committee meetings a little over a year ago. The draft ordinance ultimately went nowhere.

In addition to pending statewide legislation that would have superseded any city ordinances, the committees did not identify public support and voiced concerns about ride-hailing services' potential to harm the city's current taxi service, Checker Cab, said 2nd Ward Councilman J. Rick Mihalevich, who chairs the Public Safety Committee.

"In theory, services like Uber and Lyft could operate under the taxicab regulations. It's just that that doesn't fit their business model," Moehlman said.

Operating as a taxi company in Jefferson City requires a set of criteria foreign to TNCs' typical mode of operation.

The city specifies taxi companies must operate 24/7, keep at least three four-door vehicles road ready, and identify taxis with signage on doors and uniformity among vehicles.

Uber, on the other hand, employs background-checked drivers as independent contractors using their own vehicles, which must meet certain company specifications.

Jefferson City also requires businesses to obtain a certificate of need - which proves a new company serves a currently unmet need in the city - as a prerequisite for a license.

In September 2015, Checker Cab owner Tom Landwehr told committee members eliminating the certificate of need requirement to make way for Uber would decrease his company's profits in peak hours so much so Checker Cab wouldn't be able to operate during the non-peak hours of 2-6 a.m. - which would keep the company from meeting the 24/7 requirement.

The city ordinance, which also sets the fares taxis may charge, states only people with a vehicle-for-hire driver's permit may operate such a vehicle and be able to pass a background check conducted by the Missouri Highway Patrol.

Other cities have found ways to rectify the TNC business model with existing taxi regulations.

Columbia approved regulations in 2015 requiring city-administered background checks for Uber drivers, who must be licensed in the city as transportation network operators (TNOs), which entails an annual $20 application fee and $25 vehicle inspection.

Of Columbia's 256 licensed TNOs, 13 have Jefferson City addresses and a handful live in surrounding communities like Holts Summit and Centertown, according to records provided by the city's finance department.

Lupardus and her husband have both driven for Uber in Columbia since early this year, mostly on Friday and Saturday nights. It's a side gig for the couple, who both work full-time jobs in the city and moved there from Jefferson City in June.

"I've had weeks where the most I've made myself in a weekend was about $700," she said. "We've had some really, really good weekends, and we've had some really, really bad weekends."

Columbia's Uber market primarily serves college students, she said. "I can't say the same if it was to come to Jeff City. I think it would be very good for the government. Parking is so horrible downtown, and it's so convenient because if there's several Uber drivers running around you're going to be picked up within five to 10 minutes."

While other Columbia Uber drivers living in Jefferson City said the college town has more potential for pick-ups, Lupardus would have preferred to drive in Jefferson City while she lived here.

"We were only a couple steps out the door to our cars. We could have literally sat at home and watched TV and just turned on the app," she said.

Springfield's ordinance approved Nov. 14 omits the requirement of individual driver permits, as long as the drivers hold vehicle-for-hire licenses and the TNC they represent is properly permitted. It allows the city to investigate complaints about drivers, requiring companies to suspend operations during such investigations.

The Springfield ordinance offers a framework for wider TNC growth in Missouri, and Uber now is targeting statewide legislation rather than city-by-city policies.

"Every Missourian should have access to safe, reliable and affordable transportation options and opportunities to earn a living with greater flexibility," Uber spokesman Bobby Kellman said in an emailed statement. "We hope the state legislature will consider the common-sense framework for ride-sharing recently approved by Springfield as a model for statewide legislation."

Lyft, another leading TNC which hasn't operated in Missouri since leaving St. Louis in 2014, is playing the same waiting game.

"Lyft will relaunch in Missouri as soon as a comprehensive regulatory framework that prioritizes public safety and consumer choice is passed. Thirty-five other states have already done so, and we are hopeful Missouri will soon join their ranks," spokesperson Adrian Durbin said.

State Sen. Bob Onder, R-Lake St. Louis, plans to file a bill in the 2017 legislative session authorizing TNCs to operate statewide - which essentially would nullify any contrary city ordinances.

"These cities are political subdivisions, and they are essentially arms of state government. When we see the cities doing something that's anti-competitive, that's suppressing a new business that has the potential of creating thousands of new jobs for Missourians, having a new business that has the potential to satisfy a really big consumer demand," Onder told the News Tribune. "When we see that kind of unjust behavior on the part of the cities, sometimes we have to go in and pre-empt their ordinances."

Onder sponsored a similar bill last year, which specified municipalities could not impose licensure requirements or taxes on TNCs or TNC drivers. It would have required TNCs to screen drivers by conducting local and national background checks.

The bill's House counterpart, sponsored by state Rep. Kirk Mathews, R-Pacific, passed the House but stalled in the Senate. Mathews, too, is sponsoring the bill again in 2017.

"It might be one of the bigger economic development bills because of the flexible work opportunities," Mathews said.

Uber representatives estimated statewide acceptance could create 10,000 jobs in Missouri, he said, and he likened TNC drivers to small businesses in themselves as independent contractors.

"I do think that this is a priority for House leadership," Mathews said, noting he's confident the bill could make it through both chambers this session now that conversations have taken place with some who opposed it. "The primary concern was whether or not the transportation network companies would be required to do a background check on their drivers that included fingerprinting them. The question becomes: why would we want to impose a requirement on a new business startup that we don't require on other businesses that have a similar type service?"

Even Uber drivers earning a good paycheck in established cities could benefit from the statewide push. Without the concern of regulations changing as county lines are crossed, drivers could take more profitable trips from city to city, Lupardus said.