A penny saved is a penny earned, but saving seeds from the garden can be a questionable use of time and energy.

"Saving one's own garden seeds is a false sense of economy," according to University of Missouri Extension horticulture specialist David Trinklein. "In the world of gardening, seeds are one of the least expensive costs, but perhaps the most important investment."

Money might be saved by keeping seeds from this year's favorite plants, Trinklein said, but thrifty gardeners will likely be disappointed next year.

Most seeds produce problematic plants the next growing season.

This is because most ornamental and vegetable seeds in today's gardens are F1 hybrids, Trinklein said. An F1 hybrid is the result of a controlled mating between two parental lines carefully selected for certain traits. F1 hybrids tend to be more vigorous, uniform and productive than either of their parents, or other non-hybrid types.

The phenomenon is called "heterosis," or hybrid vigor. Heterosis, however, does not carry over from one generation to the next. Instead, it must be re-established each generation by remaking the original cross. Therefore, seeds saved from a hybrid variety will not produce a plant with the same characteristics as the plant that bore it. Progeny of F1 hybrids tend to revert in form to one of their parents.

"In very, very rare cases, seed saved from a hybrid produces a better-performing plant than the previous generation." Trinklein said. "However, the chance for this to happen is infinitesimally small."

The wisdom behind saving non-hybrid ornamental and vegetable seeds depends on many factors. For example, seed from cross-pollinated crops will be true to type only if the plants were isolated from other varieties of the same species. To preserve genetic purity, wind-pollinated species, such as sweet corn, must be isolated from other varieties by a greater distance than insect-pollinated species, such as watermelon.

Self-pollinated species probably represent the best candidates for seed saving, Trinklein said. Heirloom tomatoes are a good example because tomatoes are usually self-pollinated. Isolating saved heirloom varieties from other tomato varieties can help assure genetic purity. However, insects such as bumblebees can cross-pollinate them and mingle genes from other varieties.

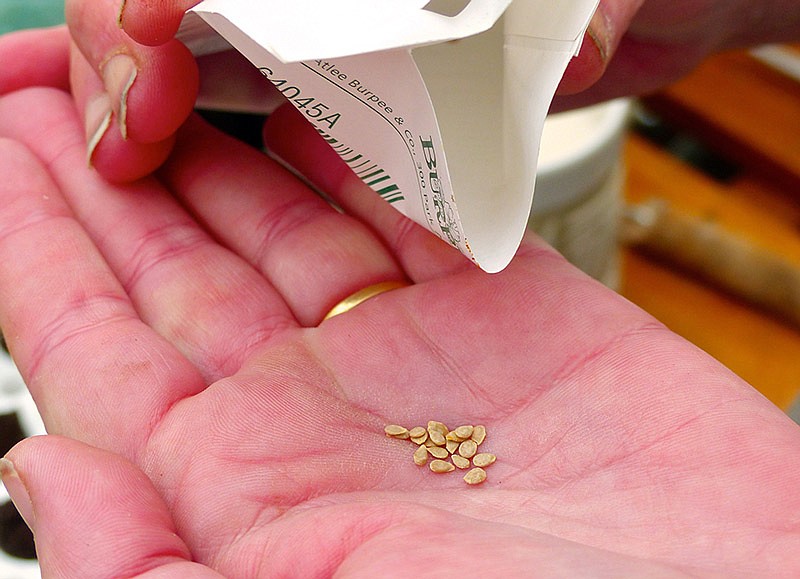

If gardeners decide to save garden seeds, they should collect only from healthy plants since seeds transmit several virus diseases, Trinklein said. Seeds should be cleaned and sorted to week out any appearing nonviable, usually smaller and lighter.

Store seeds in a cool place, such as a refrigerator, and keep them dry. A wide mouth glass jar works as a good storage container for leftover seeds from this year's garden. Place a layer of a desiccant, such as silica gel, in the bottom of the jar. Then, place packets of seeds on top of it, and seal tightly.

For more information, go to ipm.missouri.edu/MPG/2014/8/Why-Not-Save-Hybrid-Seeds.