Editor's note: Lincoln University celebrates the 150th anniversary of its founding this year. This article is the second in a three-part series on the history of the university's founders, the soldiers of the 62nd U.S. Colored Infantry.

By March 1866, when the 62nd U.S. Colored Infantry was mustered out of service, almost every soldier from its ranks had learned the alphabet, if not the ability to read and write.

Literacy was a high priority among the regiment's officers and promoted through general orders.

For example, a six-month essay contest in 1865 selected a sergeant, corporal and private from each company, giving them a gold pen or the "good book" for their work, Ron Caddington wrote in "African American Faces of the Civil War."

"No freed slave who cannot read well has a right to waste the time and opportunity here given him to fit himself for the position of free citizen," one order said. And another said, "All soldiers of this command who have by any means learned to read and write, will aid and assist to the extent of their abilities their fellow soldiers to learn those invaluable arts."

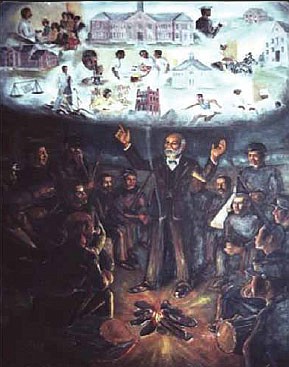

The natural extension of that emphasis, then, came from around a campfire Jan. 14, 1866, before a major consolidation of the regiment mustered out many of its officers and soldiers, including Lt. R. Baxter Foster.

"Lincoln Institute is the child of the 62nd regiment USCI," the school's first principal said in 1871. And the Missouri State Times in July 14, 1871, named Foster "its first and best friend."

At Fort McIntosh, Texas, Foster was preparing to go home. While talking of his future, Foster and Lt. Aaron Adamson discussed the success that so many enlisted men had learned to read and write.

In a casual remark without thought of practical consequences, Foster recounted how he told Adamson it was a pity no schools in Missouri existed for these soldiers to return to. Missouri's law making it illegal for anyone to teach reading and writing to blacks, slave or free, only had been repealled in 1865.

"The war has given us opportunity. It has been a grand iconoclast, breaking down idols and clearing away rubbish," Foster said in 1871. "My constant question was: Have I any special work to do, however humble in preparing this new time? And my constant prayer was, that if there were such work, Providence would point it out and show me how to do it."

Adamson had his answer: "If our regiment will give money enough to start a school in Missouri, will you take charge of it?"

That night, Jan. 14, 1866, while Foster pondered the prospect of a purpose-filled future, Adamson rallied his fellow officers to the idea and they responded with substantial donations, $1,034.60 in total.

Then soldiers from their meager and often late wages responded even more enthusiastically with $3,966.50.

Then, fellow Missouri soldiers of the 65th U.S. Colored Infantry added $1,379.50. One soldier gave $100 from his pay of $13 per month, "an example of liberality that may well challenge comparison with the acts of those rich men, who from their surplus, give thousands to found colleges," Foster said in his "Historical Sketch of Lincoln Institute."

"But two conditions were made to the gifts: that the school should be established in Missouri and that it should be open to colored people," Foster wrote. "The fundamental idea was indeed that it should be for their special benefit; but special does not necessarily mean exclusive, while in this case it means precisely the contrary.

"It is not for the benefit of the colored people to encourage the spirit of caste that would make one school white and another black. ... The caste spirit is the legitimate child of slavery, reproducing with fidelity all her temper, all the hateful lineaments of her face."

With little organization or conditions placed on him, Foster immediately requested a committee be formed to share the responsibility until a board of trustees could be formed.

"We voluntarily assumed the further condition, not imposed by the contributors, that while the officers' donations might be used in trying the experiment, the soldiers' gifts should be so guarded, that in case of final failure of the school, they could be returned."

With about $6,500 to start, Foster pursued an endowment of $50,000 and a board of directors. The logical location would have been St. Louis, as that was where the black population was greatest.

But other school prospects were at work there, and not interested in the same goals as the 62nd. So Foster looked secondarily at Jefferson City, where he found further conflict of goals and doubt of the endeavor's success.

"All seem to think that our enterprise will fail," he wrote in his diary Feb. 18, 1866.

After being turned away from both the African Methodist Episcopal Church and the white Episcopal Church for racial reasons, Foster finally secured the log room on Hobo Hill, where Jefferson City's public schools had its start, for his first two students who began in August 1866.

At a Founders Day address 1925 LU alumnus Bishop William T. Vernon, the first black man in the U.S. Treasury, said: "Truly these old men in uniform saw visions, these boys in blue, dreamed dreams. Have their visions been realized? Did their dreams come true?"