While Gail Hughes sat down to dinner at his home after a regular day as a corrections caseworker at the Missouri State Penitentiary and Warden Ralph Eidson had settled in for an evening of fishing north of town, Sept. 22, 1954, an inmate was beginning his next escape.

William DeLapp had tried several times to escape before, which is why his cell was on the top floor of E Hall, where the discipline problem inmates were kept at the time, said local historian and prison expert Mark Schreiber.

This time, he broke a water pipe in his cell and complained his bedding was soaked. When a guard entered, DeLapp overpowered him.

The next person released was William Richard Hoover and the others later named as the riot ringleaders - Paul Edward Kenton, James Stedham, Jackie Lee Noble and Rollie Laster.

They went through the hall releasing other cells, but not all inmates stepped out. Many were as scared as the corrections officers.

The riot that followed was mostly spontaneous response to opportunity on the part of another 800 or so inmates.

But three of the ringleaders had an agenda.

Two known snitches were being held in protective custody with the death-row inmates in the basement of Housing Unit 3.

Irv Thompson, Richard Lindner and a third man, whose identity is unconfirmed, reached the parole office in the Housing Unit 3, where they took officer Clarence Dietzel hostage as they took a sledgehammer to the wall.

Hours later, they entered the death row hallway where Walter Lee Donnel and Jimmy Creighton were.

Former death row inmate Samuel Norbert Reese told Schreiber in about 1970 what he heard from his cell that night.

Creighton, 51, who was the first target, blocked his cell with debris and matches. But the intruders managed to break his jaw with a knife tied to a broom handle, Schreiber said.

"Reese heard it when they killed Donnel," he said.

Donnell, 29, was the "biggest snitch in the prison," Schreiber said.

Reese told Schreiber the trio offered to kill Philip Wren, another inmate at the MSP who had testified against Reese. But he said "no."

The life of officer Dietzel also was threatened until another ringleader, Jackie Lee Noble, intervened. Noble told Screiber in 1981 he did it because Dietzel "was a decent officer who didn't mess with anybody," he said.

Education Director J.O. Dotson also faced harm, but it was inmates who did the saving, not the threatening.

A well-liked teacher, Dotson and some of his students had been blocked into the school when it was set on fire.

They used a steel pipe to pry open the bars just enough to squeeze out of the vocational center before the fiery roof collapsed. They then hid in a housing unit, giving the officer an inmate jumpsuit, until all quieted down.

In the morning, Hughes said he was relieved to see his friend.

"Everyone was thrilled," Hughes said. "It was certainly an event for us who worked there."

When Hughes left the prison at 5 p.m., "if you had told me that the place was to burn to the ground that night, I would not have believed it."

Just after dinner, he heard the governor had called in the Highway Patrol and National Guard.

"I thought, "It just can't be that bad,'" Hughes recalled.

By the time he returned to the prison about 7 p.m., it was afire, inmates were still running around and he found his fellow corrections officers armed.

He went to the hospital, where he found many wounded and plenty of chaos.

Before Hughes got the word, 17-year-old John Eidson answered his home phone to learn of the riot. He drove the family pickup out to the pond, where his father, the warden, was fishing that evening.

Young Eidson was sent back to lock up the home gun cabinet and to return the trustees, who worked at the warden's house, to their housing unit, which was outside the walls near where today's federal courthouse is.

As the youth returned to his home at the corner of Lafayette Street and Capitol Avenue, a highway patrol officer, whom he knew as a friend of his father's, enlisted his help in carrying ammunition around to the railroad side of the prison.

The officer prevented a gang of inmates from breaking open a gate with a pickup truck from the inside by firing with a Thompson machine gun. Eidson helped with the cumbersome reloading.

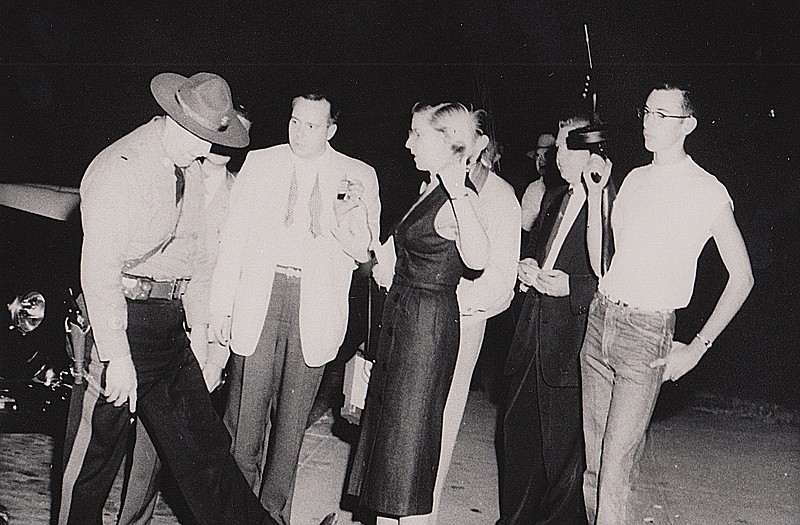

Eidson also was photographed holding the "Tommy gun" as reporters, including Jerena East interviewed the patrolmen. East, who later became Jerena Giffen, was the first UPI female reporter in Missouri.

She was dressed to meet her fiance for dinner, when she heard the first reports and saw the smoke rising. As many of the reporters who came in that night, she eventually made her way inside the walls for a firsthand account.

"You could hear sirens all night long and see the fire and smoke rising into the sky," Schreiber said.

The patrol's response was quick and powerful.

Schreiber said in "Somewhere in Time" the anticipation of a riot at the MSP became almost a joke in some circles.

But the Missouri Highway Patrol took heed of the other riots nationally and drafted a riot plan and trained officers in emergency response procedures, his book said.

"If certain inmates had had time to get places, there could have been more loss," Schreiber said.

When "rioters stormed the deputy warden's office, armed troopers on the roof were finally forced to open fire with machine guns and riot guns to force the desperate prisoners to flee the prison yard," Schreiber's book said.

Fires continued to collapse buildings as pockets of rioters were subdued.

At 7 a.m. Sept. 23, 1954, 245 troopers gathered to enter the last, barricaded building.

As the troopers entered buildings with sub-machine and riot guns, inmates were hurling debris and taunts. The loud speaker ordered convicts into the nearest cells or they would be shot. One defiant prisoner was shot and that brought an eerie silence, Schreiber's book said.

No escapes occurred.

But, "people in Jefferson City had the feeling the inmates were coming out over the walls; there was a sense of insecurity in the neighborhood," Hughes said.

And the final costs were about $5 million in damages.

"Corrections officers have the hardest job in the state of Missouri," Hughes said. "All law enforcement has risks. But every day they walk that walk in rough neighborhoods, confined for eight hours, too."