It was the biggest assignment of Joseph Ignatius Gilbert's journalistic career - and he was in serious danger of blowing it.

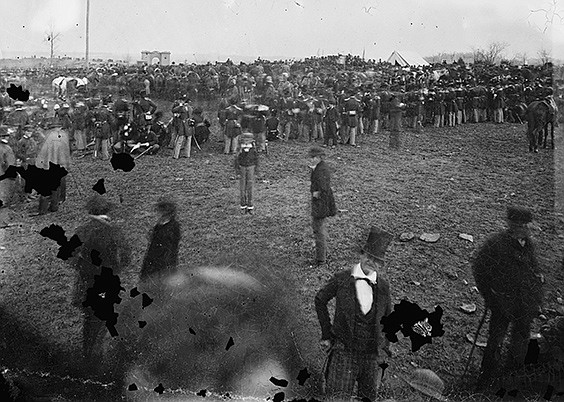

On Nov. 19, 1863, the 21-year-old Associated Press freelancer was standing before a "rude platform" overlooking the still-ravaged battlefield at Gettysburg, Pa. Towering above him was an almost mythic figure: Abraham Lincoln.

By this time, Gilbert had been covering the president for two and a half long years of civil war. Three months earlier, he had written a dispatch about the Union rout of Gen. George Pickett from this very field, an event often called the "high-water mark of the Confederacy."

Lincoln had come to dedicate a portion of the battlefield - still strewn with equipment, clothing and horse skeletons - as a national cemetery. Gilbert was dutifully taking down the president's words in shorthand when something uncharacteristic happened.

He became star-struck.

"Fascinated by Lincoln's intense earnestness and depth of feeling, I unconsciously stopped taking notes," he would recall decades later, "and looked up at him just as he glanced from his manuscript with a faraway look in his eyes as if appealing from the few thousands before him to the invisible audience of countless millions whom his words were to reach."

Luckily for Gilbert, Lincoln graciously allowed his text to be copied while the ceremonies concluded. And "the press report was made from the copy," the AP man noted.

Brief as Lincoln's speech was, many newspaper reports paraphrased or outright butchered it. In his new book, "Writing the Gettysburg Address," Martin P. Johnson argues that the fledgling "wire service" played a key role in ensuring that most Americans experienced the true power and poetry of their president's words at a time when he desperately wanted to reach them.

"The Gettysburg Address was not necessarily going to be an important text, if the first version published had been such a truncated version," he says.

But 150 years later, the debate continues over exactly what Lincoln said that day - and why it matters.

"Four score and seven years ago ..."

The speech contains about 250 words. Today, a listener with a smartphone could polish it off in 10 tweets or simply post the raw video on YouTube.

But a century and a half ago, the news medium was a reporter taking notes with a pencil, most likely in shorthand.

Once finished, he would race to a telegraph office and hand over his dispatch to an operator, who would tap it out in Morse code. The story would travel to a newspaper office, where the series of dots and dashes were deciphered, then set in lead type.

For a great many papers, the source of that text was the AP, and its "agents" - men like Gilbert.

The goateed Gilbert was a "shorthand novice" in the state Senate at Harrisburg on Feb. 22, 1861, when he first heard the new president speak in the Pennsylvania capital. His dispatches appeared in the city's Evening Telegraph. As he moved on to The Philadelphia Press and AP, the young scribe would have other opportunities to report on "the care worn President whose shoulders, Atlas-like, were carrying the pillars of the Republic."

So Gilbert was an old hand at covering Lincoln when he joined the throngs assembling on Cemetery Hill in the fall of 1863.

"The battlefield, on that sombre autumn day, was enveloped in gloom," he wrote in a paper delivered at the 1917 convention of the National Shorthand Reporters' Association in Cleveland. "Nature seemed to veil her face in sorrow for the awful tragedy enacted there."

Lincoln was not even the keynote speaker that day; that honor fell to former U.S. Sen. Edward Everett, who spoke for two hours. Lincoln's address lasted barely two minutes.

There are five known drafts of the speech in Lincoln's own handwriting, each different from the other in some subtle or not-so-subtle way. The last, penned in March 1864, is the version chiseled in marble on the Lincoln Memorial.

In 1894, Lincoln's personal secretary, John Nicolay, published what he called "the autograph manuscript" of the Gettysburg Address. The first page was written in pen on lined stationery marked "Executive Mansion"; the second is in pencil on bluish foolscap.

Johnson, an assistant history professor at Miami University in Ohio, concludes that this is the delivery or "battlefield draft" Lincoln pulled from his coat on the platform that day. John R. Sellers, curator of Civil War papers at the Library of Congress, which recently put the pages on display, agrees.

But historian Gabor Boritt, author of "The Gettysburg Gospel," argues that a version discovered in 1908 among the papers of John M. Hay, Lincoln's assistant secretary, is the one from which the president read.

Perhaps the most important difference among the address's various permutations is the presence or absence of the phrase "under God."

Those words do not appear in either the Nicolay or Hay drafts, but they are present in the three other handwritten copies Lincoln produced for use in fundraising efforts.

They also appear in dispatches sent by Gilbert and shorthand stenographer Charles Hale, who was there for the Boston Daily Advertiser, leading Johnson, Boritt and others to conclude that Lincoln added them extemporaneously.

Lincoln told his good friend, Kentuckian James Speed, that he continued to work on the speech after arriving in Gettysburg and had not had time to memorize it. He also acknowledged that he did not stick to the script in his hand.

Nicolay said Lincoln referred to the AP report when reconstructing and refining the address for the later drafts. But which one?

Due to "inevitable telegraphic variations," says Johnson, there were almost as many versions in circulation "as there were newspapers that printed them." No definitive "wire copy" survives in AP files, says company archivist Valerie Komor.

Many, including Komor, believe the story that appeared the next day in the New York Tribune, represents the dispatch sent out from AP headquarters. But Johnson notes that the Tribune had its own reporter in Gettysburg that day.

Through some forensic calisthenics, Johnson believes he has succeeded in recreating the original AP dispatch.

Different versions either include or omit the word "poor" in "far above our poor power to add or detract."

"Poor" is missing from the Tribune version, Boritt notes. It's included in the story published in the Philadelphia North American, which to Johnson "appears to be the closest approximation of the AP version as it was telegraphed from Gettysburg on the day of the speech."

Unfortunately, Gilbert's personal account only muddies the waters. In the wire dispatches, the text is interrupted six times to note applause. But in 1917, Gilbert remembered no "tumultuous outbursts of enthusiasm accompanying the President's utterances," adding the cemetery was "not the place for it."

Boritt, director emeritus of the Civil War Institute at Gettysburg College, has concluded the recollection of the AP man, who died in 1924, "needs to be taken with a grain of salt."

In the end, does it really matter whether Lincoln said "the government" or just "government?" It certainly did to him.

"The exact words are important because they clearly reveal Lincoln's thinking about the importance of the Civil War and the world historical importance of the struggle that he was engaged in," says Johnson. "He was very clear about wanting to get the words correct, precise - because he knew that it was an important point."

Johnson says "it's very fortunate for us" that Gilbert was there.

"We'd probably always have the delivery text, but that might never have been published during Lincoln's lifetime," he says. "So the Gettysburg Address might never have become such an important, iconic text for us if the AP had not been there reporting it properly."

In a paper prepared for Northern Kentucky University's SixSix lecture series, archivist Komor suggests that Gilbert's greatest contribution to our understanding of the speech is perhaps his recollection of how Lincoln delivered the final lines: "that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth."

Many who recite the address place the emphasis on the prepositions "of," "by" and "for." But Gilbert, no longer preoccupied with the mechanics of note-taking, was able to truly listen to what the president was saying, and how he said it - and he insisted Lincoln's focus was "the people."

"He served the people; he referred to them as his "rightful masters,'" Komor writes. "On the morning of November 19, Lincoln beheld his masters lying dead by the thousands."