A quarter-million children in Missouri still live in poverty.

There has been a slight decline in their numbers in recent years, but studies have found the state remains above the national average for the number of people experiencing poverty.

The 2018 Missouri Poverty Report, published by Missourians to End Poverty, determined more than 12 percent of all Americans live at or below the federal poverty level. In Missouri, 14 percent are at or below the level. And about 261,000 Missouri children (19.2 percent) live in poverty.

The U.S. government uses a measure of income to determine who is living in poverty and to determine their eligibility for subsidies, programs and benefits.

According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the poverty level for a single person in a home is $12,140; a two-person household is $16,460; and a three-person household is $20,780. For each additional person in a household, the income increases by $4,320.

In 2015, Congress asked the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine to provide an evidence-based assessment of the most effective means to reduce childhood poverty by half over the next 10 years. After years of work, the result was "A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty," which aims to identify policies that could affect poor parents' resources. The study looked at links between children's poverty and their well-being and the effectiveness of major programs.

Child Trends, a research organization that focuses on improving lives of children and youth, found there had been a general decrease in child poverty since the 1960s, but the percentage rose again during the Great Recession (2007-09).

Some researchers use a measure of less than 200 percent of the federal poverty level to identify families with low incomes, about 39 percent of children live in families under that poverty measure.

Any way you look at it, in Missouri, about one in five children live in poverty.

Donna Scheidt, who is the executive director of and has worked at the Little Explorers Discovery Center for about 36 years, doesn't see much change in the number of children who live in poverty. The center, which is licensed for 99 children, remains full.

Any decline in poverty would be good, she said. But a downturn is not evident.

"We give priorities to working poor - to those families who have nowhere else to go," Scheidt said, adding she prefers to have children in her center who come from families with a variety of incomes. "We do wish to have a melting pot."

She said the center receives children from infants to school age, and the school charges on a sliding scale. That allows the children to earn a wide range of experiences, Scheidt said.

Her own children attended the center when they were small. They were fortunate - their parents could afford necessities for them.

"I know that my daughter wanted a pair of Nike tennis shoes one year," she said. "She (realized that she) had a friend who didn't have tennis shoes at all."

That disparity put things in perspective for Scheidt's daughter, who may not have received the shoes she wanted but realized she could have shoes when she needed them.

As a general rule, families in poverty have more health problems or don't have the means to overcome illnesses, she said.

Many parents of children in her center live paycheck to paycheck. They don't get paid if they take off work to go to the doctor. They might be inclined - if a child has a fever - to give the child Tylenol and send them to school, potentially affecting other children and families.

"That's not good for anybody," Scheidt said. "Most of my parents here do an amazing job despite their incomes."

One parent who has a child at Little Explorers is Jennifer Harper, who takes her 4-year-old, Haylee, to the center every day. Harper is a single mom with three children.

The center provides child care while Harper makes what money she can working at a fast-food restaurant that opens at 10 a.m.

Beginning in mid-morning and ending late in the afternoon, the hours are challenging.

Her two boys, ages 10 and 13, oftentimes arrive home from school a few minutes before she gets off work.

The restaurant "pays decently," she said.

"But it doesn't get me out of a situation where I can afford a lot of things on my own," Harper said.

Her two boys are old enough now that they want to participate in after-school activities, but funds are limited.

Medicaid pays for health and dental care for her children.

Harper's situation is not so unusual for Cole County.

Missouri KIDS COUNT - a team of nonprofit and public- and private-sector members making up the Missouri partner of the Annie E. Casey Foundation, and whose goal is to improve lives of children - publishes a data hub online that allows users to view details about each Missouri county's unique challenges. Current and archived data may be found at missourikidscountdata.org.

On that site, it is simple to create side-by-side comparisons of how each county does in a number of categories or to pull up a single-page report on any given county.

Data on the site differs slightly from other reports. For example, the site states there were 249,829 children living in poverty in 2017 (while the Missouri Poverty Report stated the number at about 261,000).

Missouri data overall show that in 2017, 20 percent of children younger than 6 lived in poverty, 17.2 percent of children ages 5-17 lived in poverty and 32.6 percent of children lived in families receiving Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits.

The data show that, although the percentage of Cole County children living in poverty lowered between 2013-17, 17 counties leap-frogged it in the state rankings. It fell from 47th ranked to 64th in those four years.

Callaway County (18.1 percent) had the highest percentage of children living in poverty in a five-county area, followed by Moniteau (16.6 percent), Cole (15.7 percent), Boone (13.6 percent) and Osage (10.6 percent).

Data for children experiencing food insecurity - those who live in households that have problems meeting basic food needs such as having enough food as to not run out before there was money for more, affording healthy and balanced meals, or providing appropriate portions - showed Callaway County again had the highest ratio of children (17.4 percent) with insecurity. Callaway was followed by Moniteau (16.8), Cole (16.1), Boone (15.2) and Osage (13.2) counties.

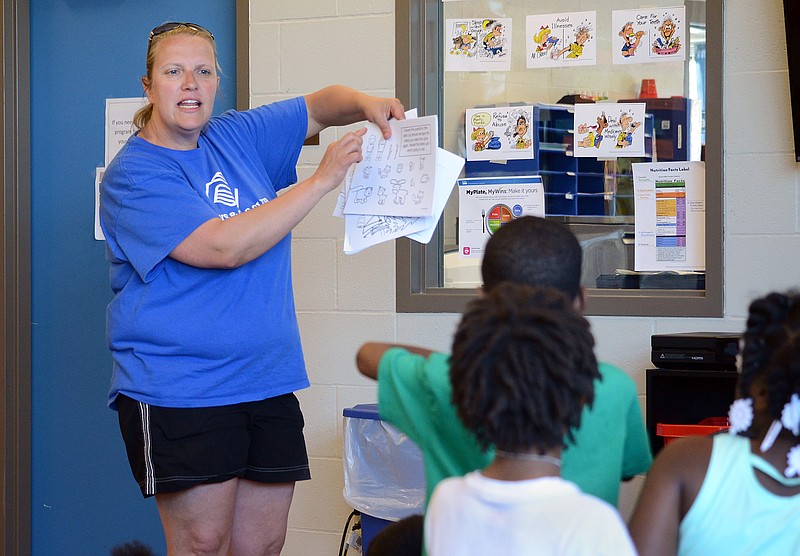

Having enough food for children is one of multiple questions people living in poverty have to contend with daily, according to Joy Ledbetter, the Boys & Girls Club of Jefferson City's social worker and family advocate.

"Poverty takes a lot of forms," Ledbetter said. "It can be an unsafe place to live; a lack of food resources; someone not being able to stay on a child about how important their education is."

People may not understand that free lunches at schools don't entirely prepare a child to be ready to learn daily, she said. They don't necessarily think of the circumstances children go through the night or morning before school. They don't know whether a child has a safe, comfortable place to live. They don't know if the child had enough to eat or even electricity.

They may not have had a parent at home the night before to help with homework because the parent had to work. Children may not have a big brother or sister to help with problems, Ledbetter said.

The "Roadmap" recommended considering program packages to support incomes, reward employment and help cover expenses of raising children. The federal government should continue reviews and research to be certain the programs put in place continue to be the most effective ways of combating childhood poverty.

Raising the minimum wage was a good first step for Missouri to reduce poverty, but it was a small step. When the Missouri Poverty Report was written, the state had not yet passed the increase to the minimum wage. The wage is to be increased to $12 per hour by 2023. It has already increased from $7.85 to $8.60 per hour.

The report defines a "living wage" in the state as one that provides sufficient income to live at a minimum standard of living, given the cost of living. It suggested a single adult with three children must make about $34 per hour to meet that standard. Two adults with three children must make about $28 per hour, working full time to meet the minimum standard of living, according to the report.

An earned income tax credits - designed to help low- to moderate-income working people - would help ease poverty, according to the report.

"Safety net programs lift Missourians out of poverty," the report states. "Each program addresses an element of poverty and influences an individual's ability to make strides in other areas of life, working toward self-sufficiency and increased overall well-being."

Gained access to health care from Medicaid expansion would help reduce poverty, it states. And as family incomes increase, the number of families who report poor health decreases. Access to good medical care would also decrease unintended pregnancies, it concludes.

The wealthiest Americans live 10-14 years longer than the poorest Americans, according to the report.

Of the more than 500 students who attend the Boys & Girls Club of Jefferson City every afternoon after school, the majority come from families living in poverty.

If they do nothing else, programs at the club help those students feel better about themselves, she said.