A traveling exhibit created by Missouri State Parks in 2018 featured a Jefferson City neighborhood. The exhibit, "BOOM!: The Rise and Fall of Missouri's Black Business Districts" included five such districts around Missouri.

Located at the base of Lincoln University roughly bounded by East McCarty, Chestnut, Atchison and Jackson streets, the area became known as The Foot. With urban renewal efforts in the 1960s and more recently the development of the Lafayette interchange, this neighborhood and its culture are now mostly gone.

The exhibit describes how black business districts arose due to forced segregation and served as the cultural centers of black life during the Jim Crow years after the Civil War up to the mid-20th century.

The story in Jefferson City begins during the latter years of the Civil War with the influx of blacks to Jefferson City seeking protection offered by the large number of Union troops garrisoned here. Prior to 1900, most city blacks lived downtown, along the alleyways. The largest concentration lived in what was known as "Hog Alley," today known as Commercial Avenue. The people who lived in this area worked as domestic servants to wealthy whites who lived nearby on High Street and East Main Street, now called Capitol Avenue. But this circumstance changed after 1900, when town whites decided to "clean up" the alleys. When the opening of the segregated Washington School in the 700 block of East Elm Street in 1904, and with housing restrictions elsewhere in the city, town blacks relocated nearby, and black businesses sprung up in the 600 block of Lafayette.

Ironically, Jefferson City became increasingly segregated as the 20th century wore on. From the time the first African American was elected to the Missouri Legislature in 1920 and into the 1960s, legislators stayed on the campus of Lincoln University because there were no places of public accommodation open to them in downtown Jefferson City.

Legislators took their meals in the Lincoln University cafeteria because downtown restaurants were closed to them as well. Although there were no "laws" that prohibited racial integration in restaurants, bars, hotels and swimming pools, local custom prohibited it.

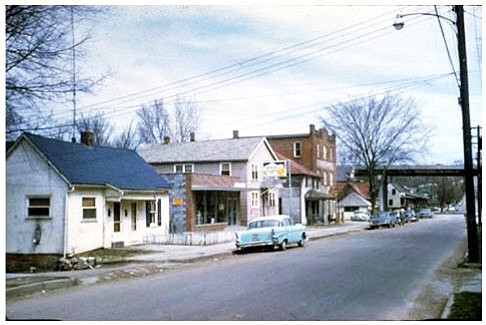

In response, black-owned businesses sprung up along Lafayette Street to serve the displaced as did a black culture. Oral history of people who grew in The Foot tell stories of the entrepreneur Duke Diggs, the weekly checkers games at a bar/restaurant at the corner of Lafayette and Dunklin streets, music jams and the challenges of getting health care and funeral services in a segregated city. The businesses there eventually included the Booker T. Hotel, Norman's Laundry, Pat's Shine Parlor, Turner's Service Station, Leona's Café, the Tops Bar and Acme Cleaners, to name but a few.

The history of The Foot can't be told apart from Lincoln University. Blacks denied access to the University of Missouri pushed for legislation sponsored by the state's first black legislator, Walthall Moore, to rename Lincoln Institute to Lincoln University in 1921. With this new status, an increase in state funding followed, leading University President Nathan B. Young to recruit an impressive cadre of Ivy League-trained scholars that included Sterling Brown and Cecil Blue from Harvard, and, later, Lorenzo J. Greene from Columbia University and Oliver Cromwell Cox from the University of Chicago. Many accomplished writers and poets were among these black intellectuals. It was a golden era that earned Lincoln University the nickname, "Black Harvard of the Midwest."

But tensions gradually developed between the black academics on university hill and the town blacks in The Foot. It was a divided black community, and all of them surrounded by a larger segregationist white community.

The Foot as it existed in its heyday is gone. The most recent vestiges of this community, demolished in 2015 to make way for the Lafayette interchange was 504 Lafayette, the home of Dr. Lorenzo Greene and professor Cecil Blue, both Lincoln academics, who described themselves as "the color boys." The "Monastery," as Greene and Blue's home became known, was the gathering place of black intellectuals.

The recently designated School Street Historic District in the 400-500 block of Lafayette is all that remains of that "red-lined" black community that surrounded The Foot.

The physical demise of The Foot was part of a frenzy of urban renewal that swept the country in the 1960s. Its intent was to modernize the city core but had little regard for the resulting destruction of black neighborhoods and cultures. Fortunately, blacks are no longer prohibited from access to services like they were before the mid-1960s, so the necessity of a community such as The Foot is diminished. Also, black academics are not restricted to teaching just at black institutions.

In his Heartland Histories, local historian Dr. Gary Kremer has captured much of the history of this neighborhood from a social historian perspective. Kremer summed up the loss of this area: ". a place is a location of experience. The experiences associated with a place do not happen anywhere else - they belong to the place. How do you re-create the place when the buildings are gone?"

Jenny Smith is a retired chemist from the Missouri State Highway Patrol Crime lab and a former editor of Historic City of Jefferson's Yesterday and Today Newsletter.