Darlene Davis has been searching for an available COVID-19 vaccine appointment in the Kansas City area at least three times a day.

Davis, a 77-year-old nurse who lives in Independence, developed a routine checking sites online for appointments.

"I go in the morning when I get up at 6. I go about 5 o'clock in the afternoon, because the government has a propensity to do things right before they go home," Davis said. "And then I go again at midnight, just because it's the start of a new day and I think that maybe something might open up then."

Davis had put her name down on nearly a dozen lists. She checked the state's Vaccine Navigator registry for mass vaccination events, only for her family to veto that option out of concern for the two-hour drive in winter to get to the nearest event in Clinton.

For weeks, her search had been in vain, with no clarity as to where she fell on the many waitlists.

Her luck finally changed Monday, after Davis secured an appointment at Truman Medical Center Lakewood.

But Davis' undertaking highlights the confusion and frustration of many Missourians in search of a vaccine, with some driving hours to more rural communities to find an available appointment.

Meanwhile, calls for the state to expand who is currently eligible - and bump up groups like teachers - have grown, even as the state endeavors to get shots to the more than 3 million residents who qualify now under the state's tiers.

However, demand continues to outpace the available supply. For the week of Feb. 15 alone, the state's website says it received order requests for more than 250,000 doses - more than 2.5 times the 93,125 doses it was allocated that week.

Lack of access

It's a demand Jan Morrow, director of the Ripley County Public Health Center in southeastern Missouri, sees among her county's residents. Morrow said she has been told to tell residents to sign up through the state's centralized registration system, Vaccine Navigator - but that can be a problem for many without internet access.

"Our computer system goes up and down - I don't know how many times a day," Morrow said. "We have people 20 miles west of us that don't have internet that live out in the rural area."

For those without internet, the state has set up a hotline for Missourians to call if they need assistance registering for an appointment. But Monday afternoon, demand was so high no one was available.

"Due to unusually high call volumes, we are unable to take your call at this time," a recording on the hotline said around 12:45 p.m. "Please call back at a later time."

That's when Morrow said her health department usually gets a call from "really hacked off" residents.

"I don't have the answers for those folks," Morrow said. "And I feel bad about that because that's not what I want for our county."

Morrow said it's unclear how the state's Vaccine Navigator waitlist will integrate with her own of upwards of 600 people. She won't be getting rid of her department's list anytime soon as she waits for her next order request for vaccine to be approved.

"While the state may think it's a great tool, it is a hindrance in this area," Morrow said of the state's system.

Where doses are going

From the Kansas City area to southeastern Missouri, residents across the state are still struggling to find vaccine.

The state has faced criticism from lawmakers from rural and urban areas who feel their constituents have been left behind, with the St. Louis region in particular calling for a proportionate allocation of doses based on population.

Data requested earlier this month by state Sen. Jill Schupp, D-St. Louis County, appeared to underscore the concern.

In the first two months of Missouri's vaccine distribution, Cape Girardeau County received enough vaccine to cover more than half of its population, while some other counties - rural and urban - didn't have enough doses for even 5 percent of their residents, a county-by-county breakdown of shipments requested by Schupp's office shows.

During the eight-week period, St. Louis city received 67,125 doses, enough for about 19.2 percent of its population. St. Louis County received 82,925 doses, enough for 8.6 percent of its population. St. Charles County received 16,825 doses, enough for 3.8 percent of its residents.

The counties of Clinton and Newtown received only enough doses for about 0.8 percent of their populations.

In a letter sent Feb. 12 to Department of Health and Senior Services Director Dr. Randall Williams, Schupp said the data confirmed her fears.

"Not only does the data show these county-by-county disparities, but it also shows regional disparities," Schupp wrote.

However, the data provided to Schupp by the state doesn't show the full picture.

Not only does it not include doses sent to long-term care facilities, but it also leaves out redistributions of vaccine between facilities and across county lines, the governor's office said in an email to the Missouri Independent.

For five weeks of the state's rollout, Missouri's share of Moderna doses were allocated to the federal partnership with CVS and Walgreens to vaccinate long-term care facility residents and staff.

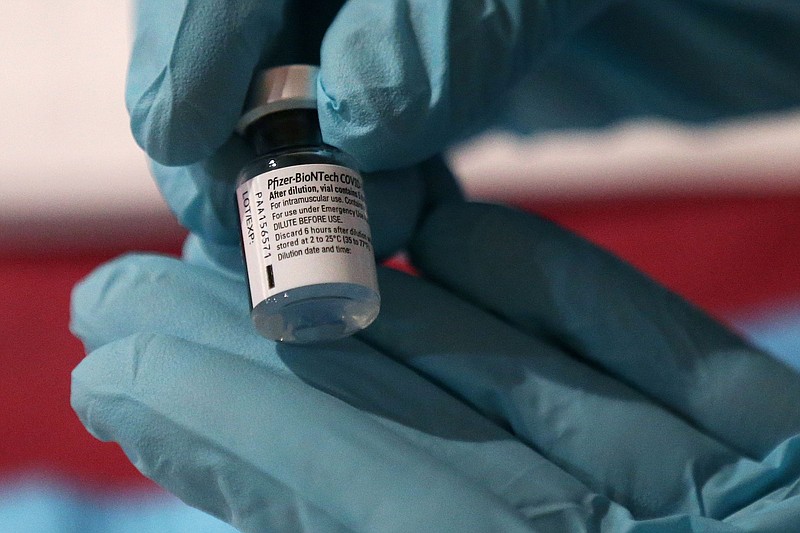

That left only doses of Pfizer's vaccine, which needs to be kept in ultra-cold freezers at minus 94 degrees.

"That is noteworthy because of the storage and handling requirements of Pfizer that prompted over 100 redistributions from facility to facility, or from county to county," said Robert Knodell, Gov. Mike Parson's deputy chief of staff.

For example, according to data provided to Schupp's office, Cape Girardeau County received 43,300 doses from Dec. 14, 2020, to Feb. 1, 2021 - enough to cover about 54.2 percent of the county's nearly 80,000 residents.

However, according to the state's dashboard, 12,058 doses had been administered to Cape Girardeau County residents as of Feb. 1 - about 15 percent of its population.

Knodell said it was designed for Cape Girardeau County to redistribute significant fractions of Pfizer vaccine to other counties.

Morrow said her department hasn't received any redistribution of doses, including from Cape Girardeau County. While health care systems in Cape Girardeau are designated as "high-throughput" providers for the region, it's not always accessible to Ripley County residents who have to drive two hours to get there, Morrow said.

A similar caveat exists for supply numbers the state released last week.

For the first time, the state published spreadsheets that detail which providers have requested and received doses and how many. However, redistributions between providers are not accounted for.

Schupp said her office was not provided any caveats to the data, such as redistributions.

Redistributions have been a tool used since the early days of the state's rollout and still continue to affect some of the largest health departments.

For example, recently the Jackson County Public Health Department and St. Louis County Department of Public Health received redistributions from hospitals in their areas after they had not received direct shipments of the vaccine from the state for weeks.

Schupp said she requested the data to ensure allocations were occurring based on population like the state said.

Each mass vaccination event supported by the Missouri National Guard has been slated to receive around 2,000 doses. Meanwhile, the Highway Patrol region that encompasses the St. Louis area makes up about 37 percent of the state's population and the region for Kansas City makes up about 23 percent.

Schupp said more populated areas should be receiving more than one mass vaccination event a week, and she would have preferred congressional districts be used to split up the state to ensure efforts would be divided more evenly based on population.

"I just feel like we were starting, in a sense, from a false premise by dividing a region that way," Schupp said.

The data requested by Schupp's office reflects only the first eight weeks of Missouri's vaccine rollout, meaning allocations of vaccine in the last three weeks to mass vaccination events with the National Guard and "high-throughput" hospital systems are not included.

While Schupp is encouraged by the state's new models to distribute the vaccine, she wants to ensure the state is bringing vaccine to the people - rather than having them drive hours to get it.

"That's expensive. And it doesn't work for everyone," Schupp said. "It gets the people vaccinated who are the people who have the most, not the people who have the least."

It's one of Davis' main worries that residents with less resources must grapple with in the face of unclear information. As a nurse who knows how to navigate health care systems, she felt better equipped to search for an appointment - and even then it was still frustrating.

For Davis, getting vaccinated means she can start to feel safer finding another job implementing electronic health records or perhaps volunteer to give shots herself. And hopefully she can see her family and grandchildren again when it's safe enough to do so.

Despite the hours of work Davis put in searching for a shot, she's not taking it for granted.

"I was just so incredibly lucky to get the right person today, at the right time," Davis said, later adding: "It's by lucky circumstance."

The Missouri Independent is a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization covering state government and its impact on Missourians.