One century ago, on July 3, 1919, Missouri became the 11th state in the nation to ratify the Suffrage Amendment (later named the 19th Amendment) to the U.S. Constitution, giving women the right to vote in all elections.

Secretary of State Jay Ashcroft's office and the Missouri State Archives are posting a short video this morning on their Facebook pages, highlighting the timeline of women getting the right to vote in the Show Me State.

"The fight for women's suffrage was a really long one," Christina Miller, a state senior reference archivist, told the News Tribune on Tuesday. "We have petitions to the General Assembly, asking for women to be granted the right to vote, starting right after the Civil War ends (in 1865).

"It was really World War I that kind of really prompted most politicians to (say that) 'women proved themselves to be citizens of this country, in everything they did in support of the war effort - so it's really our job to stop denying them the right to vote.'"

The national push for women's voting rights began in 1848, "with the Seneca Falls Convention organized by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott. Following the convention, the demand for the vote became a centerpiece of the women's rights movement," an article on the History Channel's website notes. "Stanton and Mott, along with Susan B. Anthony and other activists, raised public awareness and lobbied the government to grant voting rights to women."

At the time the suffrage movement began in the mid-1800s, women generally couldn't own property and had no legal claim to any money they might earn.

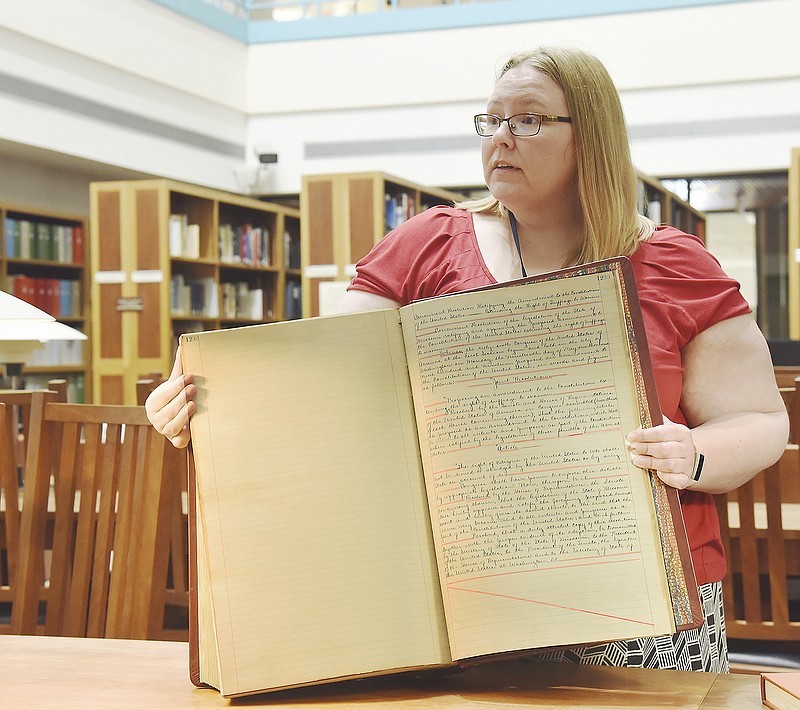

Last week, as part of its work emphasizing the history of that debate in Missouri, the Archives scanned a copy of the official document from the state's Laws of 1919, showing Missouri's ratification of the controversial amendment.

"We've been doing a lot of research lately related to women's suffrage in general," Miller said. "In April 1919, the General Assembly passed a law giving (Missouri) women the right to vote in presidential elections."

The U.S. Senate, which had rejected several previous proposals, passed the proposed amendment on June 4, 1919, by a 56-25 margin - just two votes more than the two-thirds majority needed to send the proposal from Congress to the states, where votes from three-fourths of the states' legislatures were needed to add the language to the U.S. Constitution.

"When (the amendment) was then ratified by the U.S. Senate, the governor (Frederick Gardner) called the Legislature into special session and said, 'I really think we should pass this,'" Miller said. "The House voted on it on July 2 and the Senate voted on it on July 3 - and the governor signed it on the 3rd."

However, it would be more than 14 more months before Tennessee would become the 36th, and final, state to ratify the amendment and add it to the Constitution - and Tennessee's vote was by a single, one-vote margin.

That vote was Aug. 18, 1920, and on Aug. 26, the amendment was certified as being added to the U.S. Constitution.

And just days later, women in Hannibal voted for the first time, in a special election.

"At the time Missouri lawmakers ratified the 19th Amendment, the General Assembly was all-male," Missouri House Minority Leader Crystal Quade, D-Springfield, noted in a news release. "Today, one-fourth of the legislative seats are held by women. While certainly an improvement from a century ago, it's far from where we should be."

In addition to the online video, Miller said, customers can ask the Archives to have the page ready for personal viewing - with advance notice.

"This is an item that we keep in our rare documents vault, so there's only certain people who can pull it out - it would probably be best to know in advance that they're coming so we can pull it out."

Miller said her job is to make records available for public viewing and study.

"When people have questions about how to find information or are trying to find an answer to a question, they can come to us," she explained, "and it's our job to locate it within the records of the Missouri State Archives then make it available to the researcher."

Miller has a bachelor's degree in history but doesn't consider herself to be a historian.

Instead, she said: "One of my favorite aspects of reference is, you never know what question you're going to get asked. And so I learn a lot of things about state government just based on the questions that people ask me."