From the same media family that established the People's Tribune, the business origin of today's Jefferson City News Tribune, came a wireless savant, involved in the earliest cross-continent communication with radio.

Charlton Jason Corwin brought his New York newspaper know-how to Jefferson City in the mid-1850s, operating the Jefferson Examiner before the Civil War and opening the Tribune in 1865. In 1880, he was part of the Jefferson City Daily Eclipse, where his son, Charlton Basye, worked as a newsboy. He started the Jefferson City Republican in 1900.

Charlton Basye Corwin advanced as a printer's devil at the Daily State Journal and became a reporter at the Tribune his father had started 30 years earlier. When that paper was sold to the Cole County Democrat in 1909, the younger Corwin followed his father's footsteps, starting the independent morning Daily Capital News in 1910.

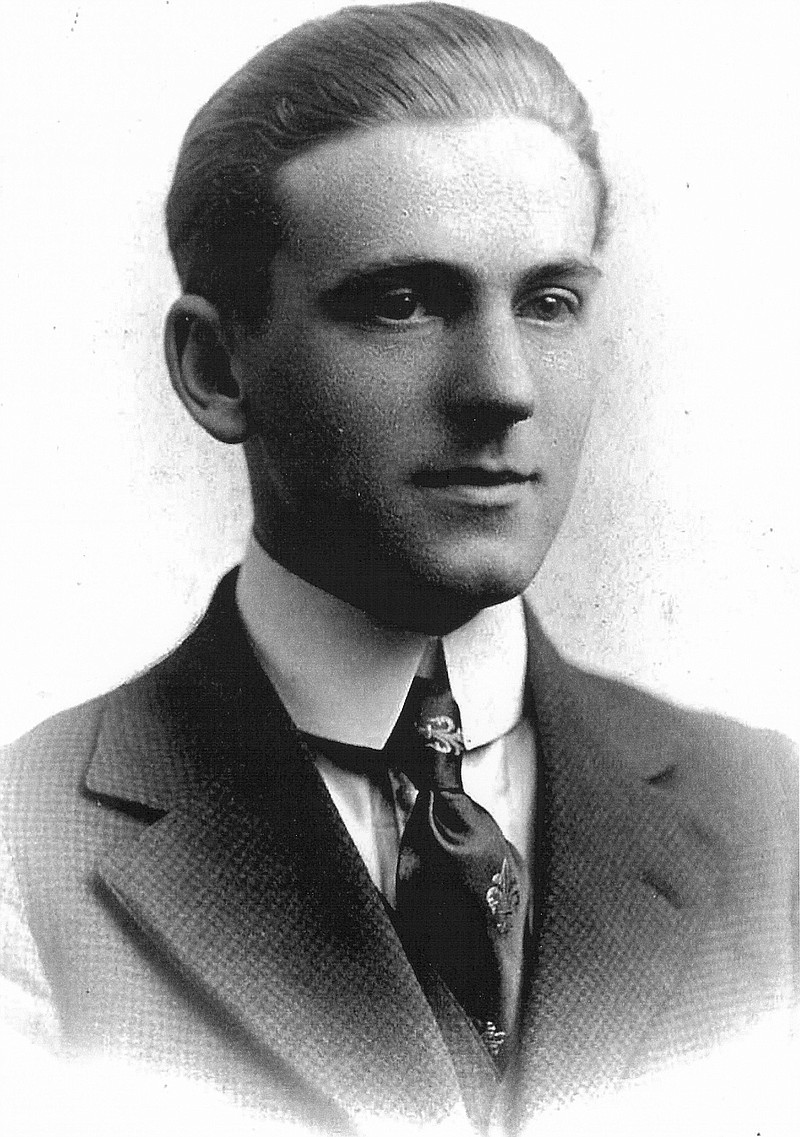

The younger Corwin lived at 117 E. McCarty St., where his son, Willis Porter Corwin, taught himself how to set up a Marconi-style radio antennae, a wooden tower and a radio station in a shack in the backyard. Since age 13, his interest in the phenomenon of wireless had him reading magazines and building his machine piece by piece.

The first message sent from his home station Jan. 9, 1916, was for local printer Hugh Stephens to his father, E.W. Stephens, in Columbia. That was followed the next month by participating in a national test, sent through wireless amateurs to 37 governors and 137 mayors, including Gov. Elliott W. Majors and Jefferson City Mayor Cecil Thomas.

The night of Jan. 27, 1917, he received and re-transmitted three Morse code messages, part of the first one-way American, transcontinental message relay. Then, Feb. 15, 1917, he was one of five stations to be part of the first two-way relay of amateur radio stations from the east coast to the west and back in only 80 minutes, "an unheard of feat in those days," said Kent Trimble, Mid-Mo Amateur Radio Club former president.

Only a few months later, the friendly amateur radio operators, who spoke nightly, made their last sign-offs. The government had asked all stations be dismantled so "no vagrant messages shall ply the air" in the looming era of war.

After the U.S. government required him to remove his amateur antennae, Willis Corwin was the first man in Jefferson City to enlist in World War I. He graduated in May 1917 and then joined the U.S. Naval Reserve as a chief electrician (radio) in France and later served as chief radio operator at naval installations in the Great Lakes area.

Returning from his military duty in November 1919, Willis Corwin attended the University of Missouri-Columbia where, in the fall of 1920, he helped a fellow engineering student set up a radio station at his home in Columbia.

The next year, Willis Corwin experimented at the university with vacuum tube transmission. This early experimentation gave him the expertise to help set up the state agriculture department's marketing bureau with a radio station. WOS was the first commercial AM broadcast station in the Capital City, the first state-owned station and among the first standard stations in the nation.

In August 1921, Corwin helped create a makeshift wireless system and aerial tower from the Capitol dome. The first transmission was sent to Sedalia, where state officials were attending the Missouri State Fair.

An improvised station with a homemade, low-power transmitter sent out its first marketing news reports on livestock and grain prices in February 1922. By that fall, WOS became the 12th standard station in the nation with Western Electric equipment and transmitter, and Corwin was the first announcer and engineer.

Willis Corwin also superintended the construction of the St. Louis Post Dispatch's KSD radio station and stayed on as its first chief engineer, pioneering wire-photo transmission. He was part of the skilled radio and telephone men who were involved in refining the methodology used to transmit President Calvin Coolidge's address to Congress - the first time a president was heard over radio waves.

The St. Louis station was one of only six national stations to make the broadcast. To prepare, Corwin listened to phonograph records being played and newspaper articles being read from Washington, D.C., and carried over telephone circuits to perfect the delivery.

Sadly, Willis Corwin was declared insane and his father was given custody of his affairs. At age 30, he was admitted to the Veterans Home in Knoxville, Iowa, where he died 29 years later. He is buried at the Jefferson City National Cemetery.

This story is an excerpt from the soon-to-be-published book by Michelle Brooks, "Hidden History of Jefferson City," through The History Press.