If the 62nd U.S. Colored Troops had a poster boy, he would be John Oscar Jeffries. He fulfilled all of the visions that could have been held for a newly freed slave from a humble Missouri farm in the 1860s.

Jeffries was born in Fauquier County, Virginia, the slave of Margaret M. Hume. He moved to Boone County in the 1850s with the family of John Scott Payne, the great-nephew of Hume, who inherited him. While there, he worked on the farm of Payne's father, Arthur, whose property was valued at $20,000 in 1860 (equivalent to more than half a million today).

At age 18, he crossed the Missouri River and enlisted in Jefferson City on Dec. 18, 1863, with the 1st Missouri Volunteer Infantry of African Descent. He mustered into the regiment, later designated in the federal system as the 62nd U.S. Colored Troops, at Benton Barracks, where Forest Park is today in St. Louis.

He moved with the regiment in March 1863 from St. Louis to Louisiana, where he became partially deaf in his right ear from the concussion of cannonading. Jeffries was assigned as an orderly to the brigade headquarters May to December 1864, when it relocated to Brazos Santiago, Texas, then to the regimental headquarters January to June 1865.

Jeffries was appointed corporal in July 1865 "for general good conduct" and worked as a clerk in the adjutant's office through the fall. In December 1865, he was promoted to sergeant major, the highest non-commissioned officer's rank and a position held by white soldiers for the regiment's first two years.

Nearly all of the 1,200 soldiers of the 62nd USCT had been freed at their enlistment. The Emancipation Proclamation did not apply to Missouri, which remained loyal to the Union. Most of the men could not read or write, as the Missouri General Assembly in 1847 had made it illegal to teach Black people, free or slave.

These men of the 62nd were fortunate to have white officers, many who had been teachers or newspapermen, and nearly all who were vocal abolitionists. From the first weeks when the regiment formed in St. Louis, officers held small group lessons and encouraged reading and writing.

One year into their service, literacy became a requirement for non-commissioned officers, and all soldiers were encouraged to spend their spare time learning their letters. By January 1866, when the regiment consolidated, one-fourth of the soldiers remaining could read, write, cipher and were studying geography. Half could read and write well and less than a dozen had not even learned the alphabet.

No wonder the regiment was keen to create a school in Missouri for other Black citizens to learn, as well. With help from soldiers of the 65th US Colored Troops, also comprised mostly of former slaves from Missouri, the 62nd founded Lincoln Institute, which opened in fall 1866.

Jeffries and many other former soldiers from many USCT regiments attended Lincoln in the years immediately following their being mustered out of service. After studying as a student, Jeffries became a teacher at Lincoln.

He was part of early African American teachers' conventions, held leadership positions in the local chapter National Equal Rights League, and served for a time on the Lincoln board of trustees.

While in Jefferson City, he boarded with the family of Franklin Rose, a railroad engineer from Indianapolis, Indiana. Jeffries worked as a church sexton and copied letters and papers for attorneys.

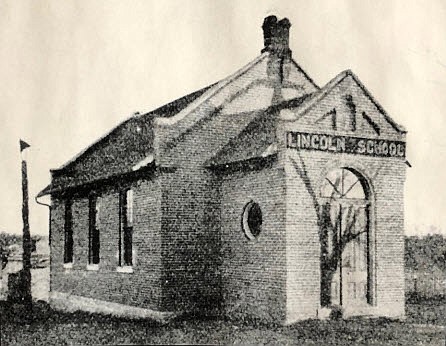

When he moved to Rolla to teach at Wilson's Retreat in 1875, Jeffries was described by the State Journal as "honest, industrious and capable." In 1882, Rolla built the Lincoln School, a modest brick school for African American students, which is in use today as a church. There, Jeffries also taught evening classes for adults.

After teaching 15 years, he opened his own business and the first steam laundry in Rolla, which he operated another 30 years. In Rolla he was involved in the People's Party and was often the keynote speaker for Emancipation Day events in August.

He and his wife, Minerva Marr, were married in 1879 and spent their honeymoon in Jefferson City. They had three children - Festus, Fillious and Eugenia. Their home at 200 N. Elm St. in Rolla still stands.

When Jeffries died in 1922, his obituary said he "was a leader among his race and worked for their uplift and benefit." Until Minerva's death in 1935, his headstone was decorated with a new flag each Memorial Day. Work is underway now to install an official veteran's marker for him at the Rolla Cemetery.

A former reporter for the Jefferson City News Tribune, Michelle Brooks has been researching Jefferson City history for more than a decade and is especially interested in the first century of Lincoln University.