By the end of 1948, there were 77 schools in Moniteau County, according to the 2000 edition of the book "Moniteau County Missouri History." Many of these schools were represented as the small, one-room school house with a single teacher. As the website SchoolMap.org notes, Moniteau County now has a total of six public school districts.

"Improved roads; newer, larger and more efficient buses; funding challenges and the push to consolidate schools contributed to the demise of the once highly cherished one-room school," an article on the website of Missouri State University noted.

"One-room schoolhouses across the United States served not only as places to teach children reading, writing and arithmetic; but as a community gathering place for business meetings and social events," the university said.

Few schoolhouses have survived the decades, with most little more than broken relics of their former glory. Regardless, many of these buildings continue to hold fond memories for the now older adults who once attended them.

Included in this extensive list is Surprise School, once located between Russellville and McGirk on Route K. For a number of years, it was the building where many local students received their basic instruction in a range of academic subjects.

"Since there weren't enough kids to open the nearest one-room school, I attended the first and second grades at California," said Norris Siebert, who was raised north of Russellville on Rockhouse Road. "But, starting the third grade in 1942, the powers that be decided to reopen the local one-room school."

The schoolhouse had burned to the ground years earlier, Siebert said. It was so quickly rebuilt that it surprised many area residents, resulting in the decision to name it "Surprise School." In the years that followed, the schoolhouse hosted students who attended grades first through eighth.

Like many of the students Siebert attended classes alongside, there was no transportation system in place, and he had to daily make the walk to school.

"Even our teacher, Ellen Messerli, walked to the school, but I think my distance was the furthest - 2 miles," Siebert said. "Occasionally a car would come by and give me a ride, but that didn't happen often."

For eight years, Don Wyss attended the one-room Enon School. He remarked that since there was only one teacher, an alternating grade level was used so the teacher did not have to instruct every grade each year.

"It fell to my lot to be a grade alternator," Wyss noted. "After grade four, I skipped to grade six, fell back to grade five, skipped to grade eight and then fell back to grade seven, from where I graduated. That system now seems strange, but actually wasn't that bad."

Wyss was approached by Oscar Siebert and Guilford Heidbreder in 1947, both members of the board of the reopened Surprise School. They sought a new teacher, and Wyss, 18 years old with only 20 college hours, was offered the job. He attended summer courses at the college in Warrensburg and completed a 10-week workshop on teaching school.

Beginning his teaching career in the fall of 1947, Wyss said, "At first, I wondered why anybody would teach school for a living, but I soon came to like it."

He added, "The students were very capable and, at the time, I did not realize that this would lead to a lengthy career in education."

One of the life-shaping experiences, Wyss recalls, came when a local woman sponsored a Jewish family that had been interred in a concentration camp in Germany during World War II. The family consisted of a young boy and girl, both of whom attended nearby Surprise School.

"The children spoke German but no English and I couldn't speak German," Wyss recalled. "I wondered, 'How in the world can I teach them?' But I discovered they could do arithmetic very well, and I would do a lot of object lessons, such as holding up a pencil and saying, 'This is a pencil,' while having them repeat after me."

In his first year, the eighth-grade graduating class attended graduation ceremonies at nearby California, where Wyss was asked by the county superintendent of schools to introduce the speaker from the state department of education.

"I started to introduce the speaker and, because I looked so young, he thought that I was one of the eighth-grade graduates!" Wyss said. "I said, 'No, I'm the teacher!'"

Wyss made the daily drive to Surprise School from his home in Enon, earning the monthly salary of $175. Occasionally, the road to the school became so muddy and poor that he parked his car at the home of Oscar Siebert, who then transported him and several students to the school on a wagon towed by his tractor.

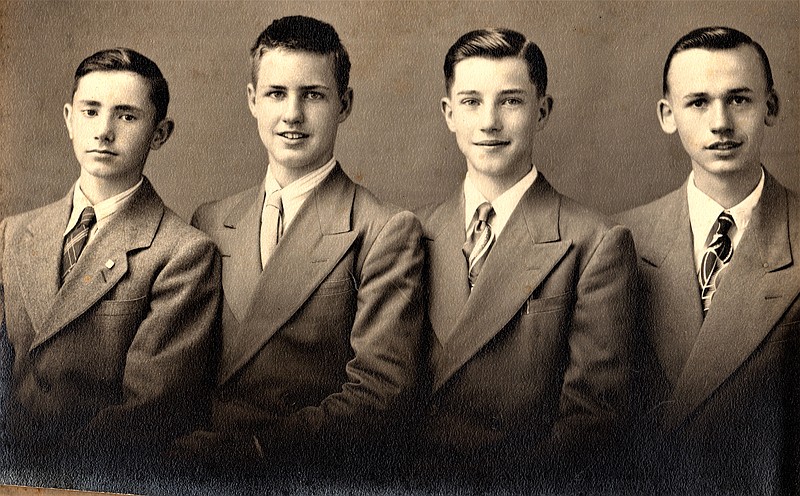

In the spring of 1949, Norris Siebert was among the three graduating eighth-grade students at Surprise School. Reflecting on his education, he noted, "I am sure we were learning high school subjects, because when I got to Russellville High school (in the fall of 1949), it just seemed like a review of what I had already learned."

Don Wyss served three years as the teacher at Surprise School, stating the educational institution closed due to consolidation of rural schools in 1950. He went on to spend more than four decades in education, but recognizes his time in a one-room school provided some of the most important lessons of his career.

"Experience is the best teacher, and I probably learned more at Surprise School about teaching and human nature than I learned from any university class."

He added, "I really believed in the rural school structure, and it was a different education from the standpoint that you learned by doing learned to make the most of the resources available."

Jeremy P. Amick is writing a series of historical articles in honor of Missouri's bicentennnial.