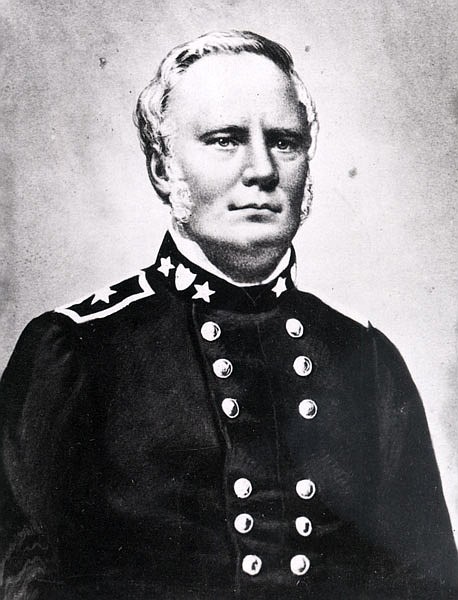

Was Sterling Price the beloved statesman Missourians knew and trusted or the man who took up arms against a country to whom he swore an oath of allegiance to three times?

Born in Virginia in 1809, Price was a prosperous slave-holding farmer near Keytesville when he was elected as a Democrat to the Missouri House of Representatives in 1836, then to the 29th U.S. House of Representatives in 1845. This term was cut short as he resigned to join the Mexican-American War effort in 1846. As a commissioned colonel, he marched the Missouri Mounted Volunteer Cavalry into Santa Fe and later into what is now Taos, New Mexico. These exploits helped his political interests back in Missouri, where he was elected governor in 1852.

Although a slave owner, Price initially opposed secession and was a Union supporter. After the Confederate States of America formed in 1861, a Missouri State Convention was called to decide if Missouri would remain in the Union. With Price presiding over the convention, the delegates overwhelmingly voted against secession.

When Missouri Gov. Claiborne Jackson refused to supply troops or supplies to the Union effort, pro-Union forces led by Francis Blair Jr. and Gen. Nathanial Lyon seized control of Camp Jackson in St. Louis and the state convention called for Jackson's removal, replacing him with a provisional government, Hamilton Gamble. It was all too much for Price, who, through initially tepid in support for the CSA, renounced his Union allegiance.

With earlier exploits in the Mexican war and success while serving office having had no major blunders or scandals, Missourians liked "Ole Pap," as he was affectionately known. This is likely why Jackson appointed him. The southern effort would need a popular leader to recruit the needed manpower in the field. In his book, "The Last Hurrah," Kyle Sinisi calls Price, "the state's most prominent Confederate and one most Confederate Missourians naturally relied upon to return and liberate their state."

By this time, Price was 52, overweight and chronically ill from malaria contracted in his Mexican war days. Except for a sound victory at Wilson's Creek near Springfield in August 1861, his Civil War career was unimpressive. Overall, Union forces managed to maintain control of the state for most of the Civil War.

Despite Price's popularity with the Missourians, he was not so popular with military colleagues. According to Albert Castel in "Sterling Price and the Civil War in the West," Gov. Thomas Reynolds called Price "devious, insincere, petulant and arrogant." Confederate president Jefferson Davis called him "the vainest man I ever met," while Price's commanding general Kirby Smith called him "good for nothing." In fairness, there was much division and rancor among the rebel commanders. They were also probably cranky as they lost grip of a Southern victory.

Price's Missouri campaign of 1864 was a last-gasp gamble. Civil War chronicler CSA Maj. John N. Edwards called it "the stupidest, wildest, wantonest, wickedest march ever made." But Price romanticized that he would snatch the Confederates from the jaws of defeat by capturing St. Louis, then the capital city and sway the coming election against Abraham Lincoln.

Price's 1,450-mile trek in 1864 took him and his nearly 12,000 rebels through Pilot Knob (a costly and meaningless victory), Union, Washington, Hermann, Linn and Jefferson City, having not achieved two of his three objectives. From there, Price lumbered west to Boonville, Glasgow, Lexington and Independence, cutting a swath of destruction in his wake. His advance westward was slow, allowing Union troops time to catch up.

While his troop numbers were adequate, their training, discipline, food and equipment were not. Price counted on recruiting southern sympathizers along the way. This did not happen. What he did attract were several thousand pro-rebel guerrillas that looted, terrorized and plundered the countryside. These bushwhackers were a constant nuisance and terror to the citizenry and likely a liability to his cause. Price's estimate of property damage on the path of the raid was $10 million.

After a crushing loss at Westport, Price and company limped south back to Arkansas. It was an inglorious loss.

Rather than surrender, Price fled with other rebels to Mexico in exile. This exodus included two Jefferson Citians - Monroe Mosby Parsons and Austin Standish - who were ambushed and murdered by bandits. Price returned to Missouri after the fall of Emperor Maximilian and died in St. Louis in 1867.

Price's legacy has largely survived the taint of traitor, perhaps due to the efforts of the United Daughters of the Confederacy and the United Confederate Veterans. They have erected many monuments honoring Confederate leaders, including Price.

As governor, he restructured the public-school system, expanded the rail network and created the state geological survey. While a success in governing, his success as a military leader was mixed, at best.

Hero or traitor? Maybe it depends on who you ask.

Jenny Smith is a retired forensic chemist with the Missouri Highway Patrol Crime Laboratory. She was editor of Historic City of Jefferson's newsletter, Yesterday and Today, for 10 years. The author thanks Bob Priddy and Jay Barnes for their suggestions in the preparation of this column.