The COVID-19 pandemic is exacerbating difficulties some families in Missouri already faced, according to a recent report from Kids Win Missouri.

Pandemic-related challenges faced by parents of color, single parents, parents of children with disabilities and special needs, and foster and adoptive parents have become more difficult during the pandemic, according to Casey Hanson, director of outreach and engagement for Kids Win Missouri.

Kids Win Missouri, a nonprofit whose mission is to further child well-being by advancing the health, education, safety and development of the state's children and their families, released "Paving the Road to Recovery for Families: Supporting Missouri Kids & Families Through and Beyond the COVID Crisis" in September.

Created through surveys and community conversations with parents from 23 counties in August and September, the report was created to help understand families' challenges as they balance children's needs while dealing with pandemic-related hardships.

Jennifer Elms, of Millersburg in Callaway County, who works as a social worker/case manager and is the mother of a 7-year-old boy, said she participated in the research. Elms works in Columbia, and her son attends school in Fulton.

"I think I have a different perspective than people in the town of Fulton," she said. "A lot of the services are in Fulton. Being able to access anything is very difficult."

When her son participated in virtual classes, Fulton Public Schools was very accommodating, Elms said.

"Internet access is probably a big (issue). Fulton Public Schools has done an amazing job providing devices and hotspots for students," Elms said. "If you asked, they said, 'Yes,' and provided it - no questions asked."

On the other hand, Columbia Public Schools had stipulations, like the student had to qualify for free or reduced-price lunches, and the household could not already have some access to the internet, she said.

What Columbia did really well was feed children, delivering meals to bus stops, she said. Fulton Public Schools provided meals for students, but they had to be picked up at the schools, Elms said.

"Fulton Public Schools was offering free meal pickup," she said. "But that was 20 minutes from home and 20 minutes back."

Other parents reported similar issues to those Elms faces.

Authors of the report identified three "key takeaways" that came about after community conversations with 50 parents and more than 100 parent surveys.

The first was that the pandemic is affecting communities and racial/social groups in different ways and "exacerbating inequities."

The second takeaway was most families felt overwhelmed by changes in responsibilities associated with juggling work, school, child care and lives at home during the pandemic.

The third was parents feel like leaders aren't providing clear communication and well-articulated plans at all levels.

Within the first takeaway, the report illustrates, economic status is a significant factor in how families coped with the pandemic as it began and continue to cope as it lingers.

"Many families that were struggling before the pandemic have found themselves in even more dire straits as the impacts of the pandemic continue to affect their communities and their daily lives," the report says. "For virtual schooling, under-served families have less access to the necessary technology, equipment, and other resources to stay connected and engaged in their education."

A number of children with special needs lost access to "hands-on" services, which threatens whether they can maintain progress in growth and development.

Economically disadvantaged or food-insecure families have, in many instances, fallen into harder times than they faced when the pandemic began, the report says. That may be because of working-hours reductions, job losses and lack of access to food or other resources.

While staying home with their children might be an option for some families, it may not be for lower-wage workers, the report says.

The Families First Coronavirus Response Act allowed employers to pay for the first two weeks an employee is quarantined, Hanson said.

"Many families have been doing this since spring and have already burned through that," she said.

Families said they used the time off to care for their children, but it wasn't nearly enough to support them during summer and when school started again in the fall.

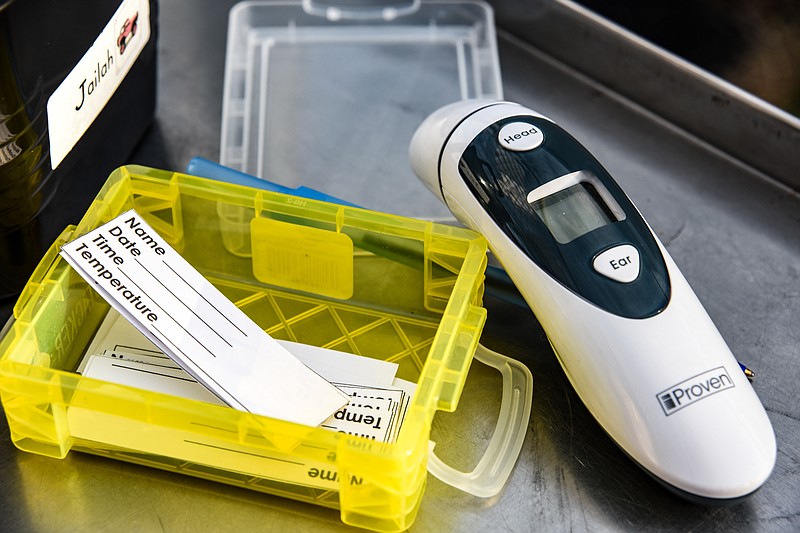

Many of the parents surveyed said they worried about health of their children as they return to school - particularly concerning children with underlying health conditions that COVID-19 may worsen. (People living in communities with low-level community spread were more comfortable sending children back to school, the report notes.)

About half of students in Missouri are now attending schools through a "blended learning style," with some days virtual and others in-person, or completely virtual, according to the report.

"Families we met with talked about the difficult position they face with trying to provide support and a more normal school experience for their children, while also tending to their professional duties. Many are working from home, adjusting their schedules to meet their children's school or care needs, or working outside of the home and struggling to find the needed assistance for their children," the report says.

Changes to their lives following onset of the pandemic were overwhelming, the second takeaway notes.

With children out of school, families found themselves scrambling to find affordable child care, but as with other industries, child care facilities cut back or closed because of the pandemic.

Those who could reached out to family options for child care.

Ninety-five counties in Missouri are now considered child care deserts, up from 63 before the pandemic, according to the report.

There are 77,000 more children enrolled in MO HealthNet (the state's Medicaid program) now than there were before the pandemic began, according to a Kids Win Missouri news release. The report does not say whether it takes into account the numbers of children going back on Medicaid after being forced off because of errors over the previous year.

The virtual learning experience also highlighted the disparities between the "haves and have-nots." Many parents said they struggled to ensure their children had the appropriate technology or devices to access the internet. Although school districts reached out to families to provide what they could, the report says, parents said they still weren't ready for virtual learning. They may not have had the proper space to provide a healthy learning environment for a child.

"(Parents of children with special needs) expressed a lack of clarity with how schools were planning to maintain the goals and plans in their children's Individualized Education Plans (IEPs) and whether or not schools would attempt to cut hours of services or access to particular services, which would violate the spirit of federal laws protecting children with disabilities," the report says. "Parents were concerned about the short-term and long-term ramifications of IEP modifications and lacked clarity on what the school's obligations would be in making up services missed or allowing for additional years of schooling if needed."

A lack of well-articulated communication at all levels was the third takeaway from the report.

"Parents' uncertainty around plans was the one common element that rang true throughout all of the sessions when talking about frustrations around school, local health orders, and decisions being made at the state and federal level," the report says. "Many parents expressed the tension in trying to understand when making decisions about preparing for school, whether to send their children to child care, or how comfortable they felt with taking their children to the doctor."

Parents oftentimes mentioned the "lack of cohesive leadership and clear communication" as contributions to their anxiety about their children.

"We overwhelmingly heard in our sessions the need for clearer communications from leadership so they can make decisions to support their families," Hanson said. "So they aren't getting mixed messages."

Some parents said schools particularly were slow in communicating.

"In many cases, whether it was someone's fault or not, changes were happening at the last minute. That was causing anxiety," Hanson said.

Many parents didn't feel that local or state governments had plans moving forward, she said.

They asked when they expected to get out from under living in a "different way." They can't see the end in sight, she said.

"And they're not getting an idea from leadership that we have someplace we're going," she added.

Authors of the report offer several solutions local and state lawmakers can support.

One is to funnel funds and resources into areas where inequities are being compounded.

"Solutions may include additional outreach and extending the flexible eligibility and enrollment requirements for families to access needed resources like child care, cash assistance, health care coverage and other safety net benefits," the report says. "Where possible, lawmakers at all levels should target resources in communities where they are most needed to help limit the widening of racial and economic disparities for kids and families."

The second is to support solutions that offer flexibility and necessary resources for families. Those solutions may include promoting flexibility and leave benefits. It may be necessary to recognize that parents are taking on additional personal and professional obligations to get through the pandemic. Additionally, leaders should target resources that support family mental health needs.

Another is to enact comprehensive strategies to ease families' anxiety and stress.

"Leaders at all levels - from the school board to the governor to the president - should communicate more robustly with families and align strategies so there is more consistency in communications to families," the report says. "This alignment and cohesion could greatly reduce the anxiety and uncertainty parents feel they are shouldering at the moment, due to lack of clear guidance and action from the top."