BONNE TERRE (AP) - A Missouri man was put to death by lethal injection Tuesday for fatally stabbing an 81-year-old woman nearly three decades ago, the first U.S. execution since the coronavirus pandemic took hold.

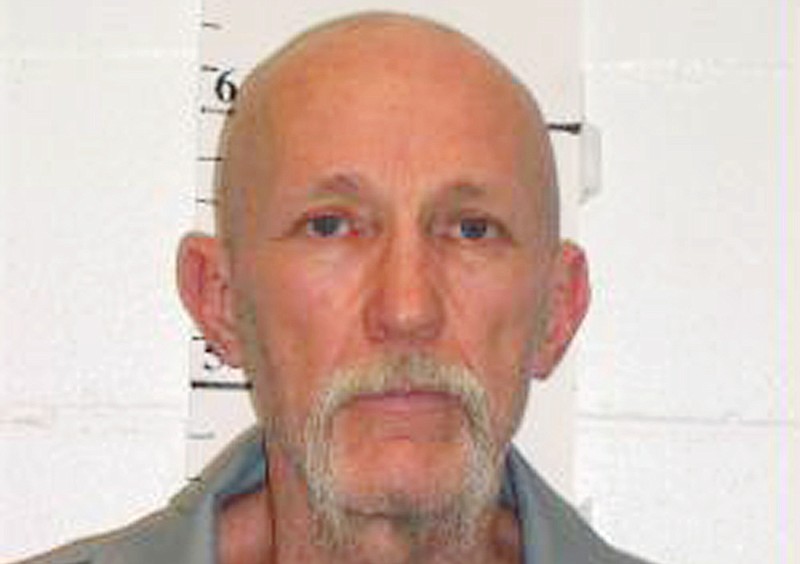

Walter Barton, 64, had long maintained he was innocent of killing Gladys Kuehler, and his case was tied up for years due to appeals, mistrials and two overturned convictions. His fate was sealed when neither the courts nor Gov. Mike Parson intervened.

Barton breathed heavily five times after the lethal drug entered his body Tuesday evening, then suddenly stopped. In his final statement released prior to his execution, Barton said: "I, Walter 'Arkie' Barton, am innocent, and they are executing an innocent man."

Concerns related to the coronavirus caused several states to postpone or cancel executions over the past 2 months. Until Tuesday, no one had been executed in the U.S. since Nathaniel Woods was put to death March 5 in Alabama. Ohio, Tennessee and Texas were among states calling off executions.

The last execution in Texas, the nation's busiest capital punishment state, was Feb. 6. Seven executions that were scheduled since then have been delayed. Six of the delays had some connection to the pandemic while the seventh was related to claims that a death row inmate is intellectually disabled.

Barton's attorney, Fred Duchardt Jr., and attorneys for death row inmates in the other states argued the pandemic prevented them from safely conducting thorough investigations for clemency petitions and last-minute appeals. They said they were unable to secure records or conduct interviews due to closures.

Attorneys also expressed concerns about interacting with individuals and possibly being exposed to the virus, and they worried the close proximity of witnesses and staff at executions could lead to spread of COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus.

Barton was executed in Bonne Terre, about 60 miles south of St. Louis, at a prison that has no confirmed cases of the virus. Strict protocols were in place to protect workers and visitors from exposure to the coronavirus.

Everyone entering the prison had their temperatures checked. Face coverings were required, and the prison provided masks and gloves for those who didn't have them.

Six state witnesses - a reporter for a Springfield television station, an Associated Press reporter and four department of corrections employees - waited in a room together for about an hour prior the execution. All six were masked. At one point, four department of corrections officials, including Director Anne Precythe and three other officials, briefly entered. They did not wear facial protection. The witness waiting room was about 300 square feet.

Facial protection was not required under Parson's statewide reopening that began May 4, but social distancing has been encouraged since the pandemic began. Parson has called the decision to wear a mask a personal choice. In fact, Parson has appeared in public without a mask.

In the execution witness room, all six state witness and two corrections officers wore masks, but Jeff Norman, director of adult institutions, did not.

However, several employees clocking in and out for the day, without masks, came into the same room used by media prior to and after the execution. They remained more than 6 feet away from the lone reporter in the media room at the time.

Witnesses were divided into three rooms. Those witnesses include an Associated Press reporter and other journalists and state witnesses, and people there to support Barton. No relatives or other supporters of the victim attended.

Barton often spent time at the mobile home park that Kuehler operated. He was with her granddaughter and a neighbor on the evening of Oct. 9, 1991, when they found her dead in her bedroom.

Police noticed what appeared to be blood stains on Barton's clothing, and DNA tests confirmed it was Kuehler's. Barton said the stains must have occurred when he pulled Kuehler's granddaughter away from the body. The granddaughter first confirmed that account, but testified Barton never came into the bedroom. A blood spatter expert at Barton's trial said the three small stains likely resulted from the "impact" of the knife.

In new court filings, Duchardt cited the findings of Lawrence Renner, who examined Barton's clothing and boots. Renner concluded the killer would have had far more blood stains.

Duchardt said three jurors recently signed affidavits calling Renner's determination "compelling" and saying it would have affected their deliberations. The jury foreman said, based on the evidence, he would have been "uncomfortable" recommending the death penalty.