As a boy growing up in Jefferson City, Arthur Brown remembers gazing through the fence at the McClung Park public swimming pool watching the white children play. He lived just a few blocks from the pool, yet he was prohibited from swimming there. If he and his brother, Glover, went outside their neighborhood for ice cream, they had to eat it outside the store. If they went to the theater downtown, they had to sit in a segregated section.

These were just a few of the ways the "Jim Crow" laws governed cultural norms. Racial discrimination was widespread and often legally prescribed from post-Civil War up to the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Travel was a special challenge for black people during those years, as even public transportation was restricted. Those who could afford their own car still were not free of the humiliation of being refused lodging, gas and meals along their routes. They could even face expulsion and threats of violence passing through "sundown" towns.

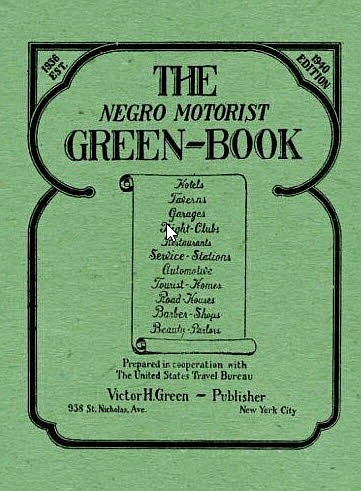

How were black travelers to know where they could get services and avoid humiliation, inconvenience and even harm? The answer came in the form of "The Negro Motorist Green Book." Created in 1936 by Victor Hugo Green, "The Green Book" provided a list of hotels, tourist homes, restaurants and service stations that would serve black travelers.

White Americans were made aware of this parallel universe that black travelers experienced through the Academy Award Best Picture "The Green Book" in 2018.

Victor Green was inspired to create this guide, like those available to Jewish motorists who suffered many of the same issues.

Listings for Missouri in the 1949 Green Book included only 16 cities with the most services in St. Louis and Kansas City. Jefferson City had the third most business listings. These were all located in Jefferson City's historic black neighborhood known as "The Foot," named for its location at the base of the Lincoln University campus.

Located just off U.S. 50 (McCarty Street before the Rex Whitton Expressway), businesses at The Foot were convenient to travelers. They could avoid the inherent hazards of driving through unfriendly neighborhoods.

The publishers listed of the following businesses in Jefferson City in the 1949 Green Book.

Hotels were Booker T, 600 Lafayette St. Tourist homes included Miss C. Woodbridge, 418 Adams St. and R. Graves, 314 E. Dunklin St.

Restaurant listings were University Restaurant at Lafayette and Dunklin streets; DeLuxe Café, 601 Lafayette St.; The Blue Tiger at Chestnut and Atchison streets, and College Restaurant, 905 E. Atchison St.

Tayes Barber Shop at Elm and Lafayette streets, C. Little service station at Chestnut and Dunklin streets, Veteran Cab, 515 Lafayette St., and Rightway Tailors, 903 E. Atchison St., were the only services listed of their kind.

The only tavern was Tops, 626 Lafayette St., and night clubs included The Subway, 600 Lafayette St., and The Lone Star, 930 E. Atchison St.

Black dignitaries and celebrities were subject to the same abuse and restrictions as other black travelers during the Jim Crow years. The Green Book guided them all to Jefferson City's Foot district.

Glover and Arthur Brown's parents owned the Tops Restaurant. Glover recounts visits from Louis Armstrong, Satchel Paige, Wilt Chamberlain, Ike and Tina Turner, Joe Torre, Ray Charles and the Harlem Globetrotters, to name a few.

Local legend tells of tennis great Arthur Ashe, who reportedly spent a summer in Jefferson City in the early 1960s. He was not allowed to practice on the nicely groomed tennis courts at the Jefferson City Country Club, regardless of his celebrity status by that time.

The Negro Baseball League teams also reportedly stopped regularly in The Foot on their travels between Kansas City to St. Louis.

The Brown brothers remember the black neighborhood of The Foot as an insulated and self-contained community. Blacks did not experience racism until they left its boundaries. With the Civil Rights Act of 1964, things changed.

Jim Crow laws became a thing of the past, as did The Foot neighborhood when Urban Renewal moved in. Unfortunately, racism continued to plague the displaced community of The Foot for years to come.

The 500 and 600 blocks of Lafayette Street, the heart of The Foot business district, is now tennis courts and green space with the Rex Whitton Expressway looming over head.

In the introduction to his Negro Motorist Guide, Victor Hugo Green foreshadowed, "There will be a day sometime in the near future, when this guide will not have to be published. That is when we as a race will have equal opportunities and privileges. It will be a great day for us to suspend this publication for then we can go anywhere we please without embarrassment."

Jenny Smith is a retired chemist with the Missouri Highway Patrol Crime Laboratory and former editor of Historic City of Jefferson's newsletter "Yesterday and Today."