FULTON, Mo. -- The leadership of Westminster College in Fulton testified in court just two years ago that the school was running out of options to avoid closure. This summer, the current president said his administration has a three-year plan to address the school's financial troubles.

Westminster's leadership petitioned the Circuit Court of Callaway County in 2016 to grant the school unrestricted access to millions of dollars of restricted general endowment gifts. In part, that request was to cover financial deficits. But leaders also sought to pay for improper withdrawals from endowment funds that had already happened. College leaders testified the withdrawals happened because of a combination of loose financial controls and diminished revenues. Then-President Benjamin Akande testified the withdrawals happened in an attempt "to keep the lights on."

A judge granted Westminster's petition - but because of the improper endowment withdrawals that came to light in court, the judge added conditions that ultimately made Westminster's annual audit information publicly accessible for several years.

Those audits - along with tax records that nonprofit investigative newsroom ProPublica made publicly available - show the history of Westminster's financial difficulties and point to what the college needs to achieve financially in the future.

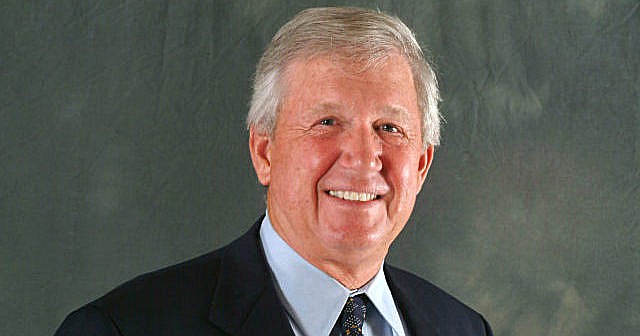

"There was not a viable financial model in place to sustain the college," current President Fletcher Lamkin told the News Tribune of what the situation was when he returned to his position in November after Akande resigned in August 2017.

Carolyn Perry served as interim president between Akande and Lamkin and is currently vice president for academic affairs and dean of faculty at Westminster.

Lamkin previously headed Westminster between 2000-07, leading the school during what one assistant dean referred to as the college's "greatest era of student growth."

The college needs significant growth in its enrollment in the coming years. Like every small private college, Lamkin said, Westminster is "highly dependent on tuition revenue.

"You've got to build your budget on that. You can't build your budget hoping that somebody's going to die and leave you $1 million, or that you're going to have a certain level of alumni giving. You've got to build your budget on having your tuition and fees revenue come close to your operating expenses, and we're not there right now."

Deficits, losses and cutting expenses

Westminster's expenses were more than $15.8 million greater than the college's revenue between the 2007-16 fiscal years.

The school's liquidity also steadily declined over time. In 2007, Westminster's expendable assets would have been able to cover expenses for almost three and a half years.

By 2016, the college's assets would have lasted less than two years in a crisis.

After 2007 and through 2017, Westminster's net assets shrunk by more than 2.5 percent per year on average - more than approximately 24 percent in total.

The school's endowment was more than $11 million smaller in 2017 than in 2008 - a decrease of more than 18 percent.

Westminster had been drawing on its endowment at a rate of 6 percent annually until this year, when the rate was reduced to 2.3 percent, Lamkin said.

"Yes, there are some efficiencies and belt-tightening that we can do. But, in one year, we've cut our (operating) deficit by $1.5 million, and we will continue to cut that over the next three years," he added.

He said the school did not reduce any faculty positions in the past year.

"We're hiring faculty. In some cases, we made changes in the discipline. But in every case where a faculty member has left, we have a replacement," Lamkin said. "There have been some staff reductions, and there's a couple areas where we've outsourced to save money."

In terms of staff reductions, he noted, the seven vice presidents there when he arrived in November are down to five.

"I had an office full of people. They're gone now, except for my executive assistant. There's two of us now, but there used to be a couple student workers, another assistant and a chief of staff," Lamkin said.

The cutbacks have been made "without sacrificing the quality of the student experience, and we've actually enhanced, I think, our ability to enroll new students," he said.

To get in the black, he said, Westminster will need "$4 million of unrestricted alumni giving for the next couple of years as we narrow that gap. I'm confident we can do it, but it is not something I always want to do.

"To get $4 million for the general fund requires an understanding alumni base, because most alums will want to give to a scholarship or a specific capital project or something like that. You just have to say, 'OK, right now we need this bridge, and here's the plan - we're not going to need this bridge after three years, but help us get through,'" Lamkin said.

So far, he explained, alumni are on board with that message.

"Last year, our unrestricted giving was about $5.4 million - there are checks that aren't in yet - so we exceeded it by a considerable amount last year, but we need to be successful for two more years at the time we build enrollments through retention and new enrollments. I think at that point, along with some efficiencies that we've instituted, we'll have a sustainable financial base," he said.

The $5.4 million in unrestricted giving was part of more than $10 million in gifts in total - the remainder being restricted to specific things such as projects, scholarships or fraternities, he added.

In the meantime, the school is "in good shape from a cash flow standpoint," he said, and he does not have any immediate concern about the college being able to pay for emergency expenses.

He said the way to keep from depending on alumni every year for $4 million is to have 300 new student enrollments, which equates to about $4.5 million in revenue.

"We are built for 1,000 (students), and we're at 700," Lamkin said. " Our new enrollments this past year were only 209 (students), and we should be bringing in 300."

New students refers to freshmen and those who transfer in. As of Aug. 20, Westminster expects a total enrollment of 711 students - about 25 more than had been budgeted.

Attracting more students

"Financial difficulties are a function of enrollments and some inefficiencies in our operation. When I say enrollments, I mean total enrollments. Retention in the past year of our freshmen was around 71 percent - 71, 72 percent last year, fiscal year 2017. Fiscal year 2018, which is the year that we just finished, our retention appears to be around 78, 79 percent, so we've gone up to a respectable level there," Lamkin said.

"You have to do everything right to retain students at the rate that we should. We used to retain 84 percent of our freshmen. We used to retain 91, 92 percent of our upperclass students, and the four-year graduation rate was above 65 percent. And that's what we need to do.

"We've fallen because we've looked at other ventures. For example, we had this remote campus in Mesa that we tried to implement. That took a lot of time and energy that should have been devoted to students right here," he said.

One way Lamkin said Westminster is trying to increase enrollment is a reorganization of its enrollment services, "so that we've got representatives in St. Louis, southern Illinois, Arkansas, Texas and Oklahoma, so that we have those live-in people working in those districts, as well as enrollment reps who cover Missouri with an emphasis on Kansas City and Mid-Missouri.

"We've got to do better in our new enrollments, get back to where we were, and we're staffing ourselves now to be able to do it. We've got a good vice president and a good staff," he said.

Growing and protecting the endowment

Enrollment isn't the only number Lamkin would like to see grow at Westminster.

"I think the endowment should be doubled. And the way that you do that is through wise investments and frugal spending," he said.

"The endowment stands at over $50 million, and the endowment draw policy is that for those endowed funds that are above water, we'll draw 2.3 percent to support whatever the activity is that they're due to support. We're going to live by that."

"Above water" means "the market value is greater than the corpus, because you should not dip into the corpus of an endowed fund," he explained. "That's something that I take very seriously. It's something that we'll make sure it doesn't happen."

A corpus is the original body of gift, and a college is allowed to spend only the interest off of that main sum if the gift is restricted.

"Most of our funds at this point are above water," he said. "There are a few isolated cases where we can't spend from those because either they're not above water or the restrictions on those funds are something that we can't meet," such as scholarships for students of specific backgrounds or identities if no such students are enrolled in a given year.

The 2.3 percent draw "is one that has an 80 percent chance of never dipping into the corpus," Lamkin said.

"That's why it's 2.3 percent. It's balanced against the way the investments are done and the expectations of the endowment growth."

The 2.3 percent endowment draw policy is pretty frugal, he said. The endowment is invested with Commerce Bank in Kansas City, and experienced businessmen and investors who serve on the college's investment committee follow Commerce's advice "in making sure that have the investments in the right place. In the long haul, that's how you build your endowment," he added.

Lamkin is confident safeguards in place will prevent the kind of improper endowment withdrawals that came to light in court two years ago.

Then-chief financial officer Joey Stoner testified in Callaway County Court in 2016 that the system by which the improper endowment withdrawals happened had been in place for an unknown number of years - since before he and then-President Akande took their positions at the college.

Stoner testified that system had placed endowment funds in the same bank account as the college's operating funds, which ultimately exposed the endowment money to the risk of overdraws because of increased operating deficits. A lack of internal financial reporting meant the problem went unnoticed for some time.

He said the college no longer deposits restricted and temporarily restricted funds in the same account as operating money, and the state attorney general's office requested a procedure established to prevent endowed funds from being accessed without approval from the Board of Trustees.

The News Tribune reached out to former Westminster President Akande and former CFO Stoner, but did not receive a response from either after multiple attempts.

Lamkin likened the financial protections in place at Westminster to his experience in the military as an officer in nuclear surety - ensuring nuclear weapons and their components are not vulnerable to being lost, stolen, sabotaged, damaged or being used without authorization.

"(Nuclear surety is) very much like financial controls - two-man rule. Nobody does anything without it being checked by somebody independent. In finances, you do the same thing. When you write a check, somebody counter-signs the check. When you withdraw from the endowment, there's somebody at the right level who's going to say 'whoops' if you've done something improper.

"We've got a number of structural policies in place so that our trustees are very involved anytime we touch the endowment."

Lamkin added: "What I make sure of is that we follow existing policy anytime we make a withdrawal or if a gift comes in to make sure that the gift is designated and placed in the right spot, rather than just spent, and we do that."

Envisioning a future

"I would like Westminster College to be known as the very best college in the country for educating leaders of character for a global community. Think I can do that in five years? Probably not," Lamkin said.

More specifically, he said, in five years he'd like to see an enrollment of 1,000 students, around a 70 percent four-year graduation rate and an endowment of around $75 million.

"Of course, I'd like to see our new stadium full every Saturday for the soccer and football," he added.

"Those are pretty modest goals. They're all achievable, but if you dream too big - you've got to dream big, but if you dream crazy big, then you won't get anywhere."

See also:

Court case disclosed how Fulton college improperly diverted millions of dollars of endowment

Westminster's Mesa campus closed within first year