Editor's note: In honor of Black History Month, this story chronicles the life of one of Lincoln University's earliest advocates.

One of Lincoln University's earliest advocates and the first black man to run on a statewide ballot in Missouri has no grave marker.

Howard Barnes' wife, Sallie, is buried in the Longview Cemetery in the midst of others reinterred from Hedge Grove Cemetery.

City Cemetery Resources Board Chairman Nancy Thompson surmises he might be buried beside her in an unmarked plot - or because she died first, perhaps he was buried with her.

"I can't believe they could bury a man like that without a stone," she said.

Barnes and his sons were instrumental in securing land from the city for a "new" black cemetery in the 1870s, after the first was so full they were burying two to a plot.

"I can't imagine he'd be buried anywhere else if they were all so involved," Thompson said.

Barnes is but an example of several unmarked burials Thompson suspects are in the reinterred Hedge Grove area.

When most black people died before 1910, when death certificates became standardized, they didn't often receive an obituary in the newspaper, making it difficult to trace who might be buried there.

Barnes is the exception, with a well-documented life, yet without a tombstone.

Known as "Uncle Howard" by legislators and leaders alike, Barnes was born Feb. 6, 1816, near New Franklin. As a boy in Howard County, he was playmates with Kit Carson.

He was cook for a contingent of Howard Countians who headed to California in 1849 during the Gold Rush, where he met up again with Carson in the Rocky Mountains.

Barnes' master had been Thomas Jefferson Boggs, brother of Gov. Lilburn Boggs. With Boggs, Barnes "witnessed fights with savages in his youth and escaped massacres that would make the blood curdle," the Sedalia Democrat reported Sept. 25, 1899.

He was given the opportunity to buy his own freedom for $2,200 in 1851, then he continued to work in San Francisco to earn the $4,000 needed to free his wife and four children. Not having all of the money at once, he accepted a loan from a Californian.

"Uncle Howard is probably the only man in the country who ever gave a deed of trust on his family but this is literally true of him," the St. Louis Republic reported Aug. 4, 1901.

Before the Civil War, the family, including his mother, Sylvia, relocated to Jefferson City.

His cooking prowess was renowned at the Delmonico Restaurant in the Virginia Hotel, later Central Hotel, where he worked for about 40 years.

Barnes "conducted a restaurant that was the resort of all the prominent public men who visited the capital during and between sessions of the legislature," the St. Louis Republic reported.

And the State Republican wrote Feb. 8, 1894, "Politicians from all over the state will remember him as one of Jefferson City's landmarks."

Even Eugene Field, briefly a government correspondent and a children's author, was fond of Barnes' cooking, writing to a Chicago newspaper from Europe that "he would give $50 if he could be back in Uncle Howard's restaurant for one single meal of roast coon," the Jefferson City Daily Tribune wrote July 5, 1914.

"He was very old fashioned in his ways, but he believed in giving people their money's worth when they came to his restaurant for a feed, and he lived strictly up to this rule all his long life," the Daily Tribune continued.

Barnes took an active role in community life early on, being an organizing member of the Capital City Lodge No. 9, Colored Masons, established Dec. 20, 1866, serving as a master and a secretary.

At Second Baptist Church, he served as a deacon and trustee, as well as clerk about 1873 when the church elected its first regular pastor.

At then-Lincoln Institute, he served on the board of trustees, even offering some of his own property as security for the school's construction in the 1870s.

When Lincoln was threatened with foreclosure, Barnes persuaded local lawyer J.E. Belch to run for the Legislature and put through a bill for the state to rescue Lincoln from financial chaos, the Daily Capital News reported Jan. 26, 1966.

Although that initial effort failed, because the state constitutionally was barred from supporting a private school, it paved the way toward Lincoln becoming a public institution.

Upon his death, the black-owned Kansas City newspaper, the Rising Son, wrote: "once a regent of Lincoln Institute, and one of its early promoters, the institution has lost a tried and worthy friend."

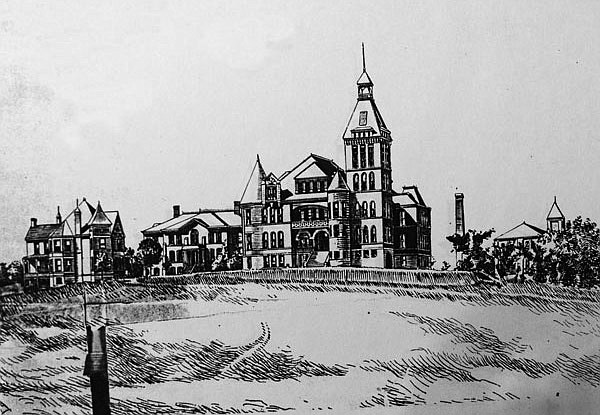

The Barnes-Krekel Hall, demolished in the 1960s, at Lincoln remembered Barnes, as well as Judge Arnold Krekel, another trustee and advocate for the school. The 12-room building served as a girls' dorm, campus dining and recreation hall after opening in 1882, according to Arnold Parks' Lincoln University 1920-70.

He ran for mayor of the Capital City in 1874.

The April 17, 1874, State Journal said: "patiently and obscurely has he been doing his duty. Steadily and sturdily has he pursued the even tenor of his ways, turning neither to the right nor to the left."

The article described him as honest, industrious and persevering.

Barnes' daughter Eliza, who also is buried at Longview Cemetery, died in 1878 of typhoid fever while studying to become a teacher. Her brothers Henry and Hannibal also are buried there with the family.

By 1880, Barnes had amassed a fortune of approximately $50,000, the Osage Valley Banner in Tuscumbia reported Sept. 30, 1880.

That year, the state Republican Party elected Barnes to the statewide ticket, running for railroad commissioner.

A Mr. Burell, from Cole County, said at the convention, "It was nothing but justice to the colored people as they constituted a large portion of the Republican Party in the state, that they should have a representative on the state ticket."

Barnes lost the race to George Pratt, 149,854-208,721, according to the 1881 state directory.

In 1882, the New York Times reported on the national Colored Men's Convention in Jefferson City, where J. Milton Turner was elected president and Barnes as treasurer.

"No caucasian or negro is better known in Missouri than Howard Barnes," the Sedalia Democrat wrote. "He has been personally acquainted in his humble way with every governor of Missouri since the Mexican War and every state officer and every U.S. Senator."