For 22 months, Jerry Koenig hid in a shallow trench under a barn with 10 other people in the hopes Nazi soldiers wouldn't find and kill them.

When he finally emerged, his body was frail and his skin was a stark white from hiding in darkness. He said he'll never forget the look on the Soviet soldiers' faces when they saw him. He barely looked human, he said.

Much of his family didn't survive the war, and he'll never know how they died - if it was in the gas chamber of a death camp or from hunger in a Polish ghetto.

Students at Helias Catholic High School listened to Koenig's story on Monday. Helias English teacher Sarah Kempker has spent the last month teaching them about the Holocaust and said Koenig is one of the few remaining Holocaust survivors.

"I think this is a once-in-a-lifetime experience, and unfortunately the opportunity to meet a survivor is limited to the near future," Kempker said.

The beginning of Koenig's nightmare was September 1939, when Germany invaded his home country, Poland. It started with bearable suffering and quickly escalated to Jewish people being segregated in packed ghettos where many starved or died of disease; then came the concentration camps and death camps, he said.

His family was transported to Warsaw, the capital of Poland, where at one point 500,000 people lived in the ghetto littered with lice.

"It became obvious that food was going to be a problem," Koenig said. "If you had to live on the amounts of food you were getting on your ration card, you were doomed to die."

Food was smuggled over the brick wall of the ghetto for a hefty price. Anyone who was caught was pressed against the brick wall and shot as a warning to others. Koenig said he was strong enough to climb the wall, but never did.

"Even so many years later, there's still guilt that I did not do what I could have done to help my family survive," he said.

His immediate family managed to escape the ghetto, eventually making their way east to live in the barn of a family who helped hide them.

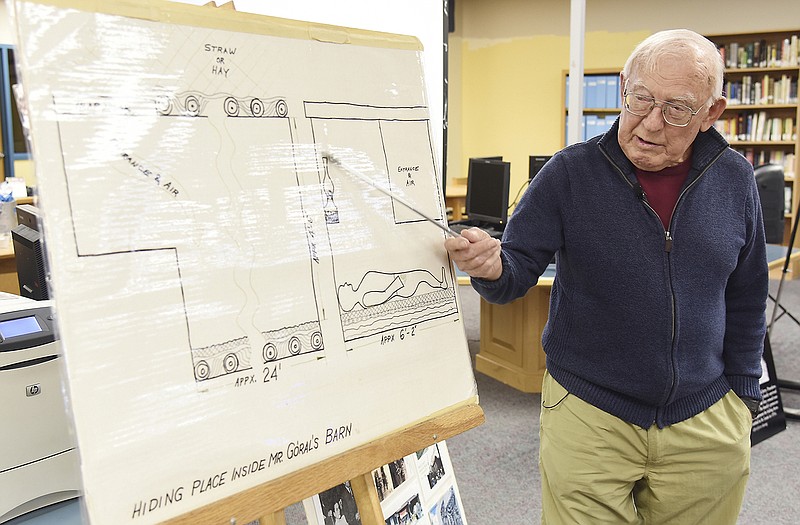

The trench was 24 feet by about 6 feet - just enough room for 11 people to lie side by side. With it only being 4 feet high, only Koenig's younger brother was short enough to stand completely vertical.

They were fed a pot of soup and a loaf of bread once a day, depending on the conditions; and their bathroom was a chicken coop attached to the barn. They couldn't bathe or protect themselves from the masses of lice and insects that crawled under the straw of their hiding place.

"We were fortunate compared to those in the concentration camps," Koenig said.

Probably the most haunting part of the 22 months in the trench was when one of the women, who had joined them in hiding after escaping from the Treblinka death camp, gave birth to a daughter.

"After the girl was born, the girl kept crying - and with good reason: she was being eaten alive by lice," Koenig said. "The adults got together and decided the girl had to go. That in and of itself had a tremendous effect on my brother and me."

They poisoned her, and she drifted off into a sleep that she never awoke from.

Koenig and his family were liberated in 1944. By the time the war had ceased, about 3 million Jewish Polish citizens had been wiped out in one way or another from the war, he said.

"Anti-semitic murderous action" was taken against Jewish survivors in Kielce, Poland shortly after, which forced him and his family to escape to the United States. They moved in 1951 to Davenport, Iowa, where a Jewish community had offered to sponsor them.

His family later moved to St. Louis and opened a grocery store, which was among their only options because they didn't speak English.

In 1997, Koenig and his wife, Linda Koenig, went back to the barn he had bunkered in.

"To me it was very difficult. I'm glad we went; I'm very glad we went," he said. "To me it was like visiting a cemetery: too many memories and too many things happened.

"I should have said at the very beginning, it's an ugly story," he said. "A story about murder sponsored by a government. ... The sad thing about it is since that time, many more bad things have happened."

Tenth-grade student Katherine McDonald said listening to Koenig's account of the Holocaust was a great privilege, one that will become rarer as time goes on.

"Something I'll take away from this is how they all had to rely on the kindness and trustworthiness of their friends who hid them," McDonald said. "(The Holocaust) is important to learn in today's society because it's hard to believe these things happen and we want to make sure history doesn't repeat itself."

Koenig ended his speech with words of wisdom to the students. While he said he will never understand why people are still interested in something that happened 70 years ago, he appreciates that they are.

"All I can say, you've got your lives ahead of you, and I want you all to go down the right path."