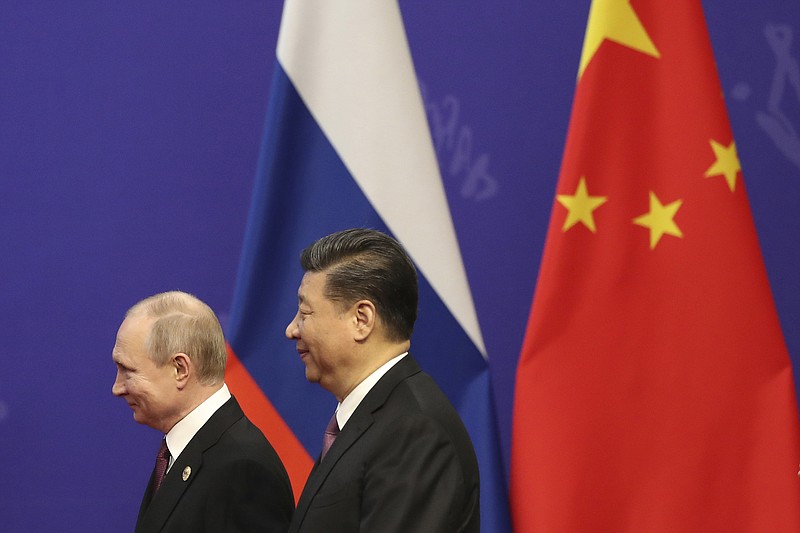

MOSCOW (AP) — Russia’s Vladimir Putin and China’s Xi Jinping have established themselves as the world’s most powerful authoritarian leaders in decades. Now it looks like they want to hang on to those roles indefinitely.

Putin’s sudden announcement this week of constitutional changes that could allow him to extend control way beyond the end of his term in 2024 echoes Xi’s move in 2018 to eliminate constitutional term limits on the head of state.

That could give them many more years at the helm of two major powers that are frequently at odds with Washington and the West over issues ranging from economic espionage and foreign policy to democracy and human rights.

Both moves reflect their forceful personalities and determination to restore their countries to their former glory after years of perceived humiliation by the West. They also mesh with a trend of strong-man rulers taking power from Hungary and Brazil to the Philippines.

Russia and China are on another level though when it comes to influencing international events — China through its economic might and rising military, Russia through its willingness to insert itself into conflicts such as the Syrian one and to try to influence overseas elections through misinformation or make mischief through cyber attacks.

Putin “believes that Russia is more powerful today than it has been since the end of the Cold War, including in places such as the Middle East,” said Ramon Pacheco Pardo, of the Department of European & International Studies at King’s College London. “Thus, it is a good time to remain in power and use this power.”

How much of a challenge he and Xi are to Western models, values and multiparty democracy depends on where you sit. The China-Russian model inspires emulation among some in both smaller powers and major nations. President Donald Trump has praised Xi and Putin, even while the U.S. battles their countries for economic and strategic dominance.

China touts its authoritarian system as providing the stability and policy continuity that has made it the world’s second-largest economy and pulled some 700 million people out of extreme poverty. Many Russians have backed Putin for standing-up to the West and improving their quality of life following the chaos after the fall of the Soviet Union.

“Political competition between different systems of governance in the world is nothing new,” the European Union’s ambassador to China, Nicolas Chapui, said. “I feel that we need to feel confident on our principles, our values, our governance system.”

In both their cases, Putin and Xi reflect the tendency of authoritarian leaders to hang onto power for as long as possible and to “die with their boots on,” said David Zweig, professor emeritus of social science at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

“Very few authoritarian leaders give up power, always convinced that only they can save the country, which also justifies and makes their hunger for power morally correct,” Zweig said.

For all their similarities, Xi, Putin and the systems they run have distinct features. Xi has repeatedly cited the fall of the former Soviet Union as a cautionary tale, saying its leaders failed to firmly uphold the authority of the ruling Communist Party.

China’s ruling communists have crushed all opposition and are tightening their hold on the economy and what remains of civil society, all while projecting an exterior image of seamless unity around Xi.

Russia at least maintains some of the forms if not the functions of a multiparty democracy, even as Putin, the security services and the oligarchs who run the economy call the shots.

Blunt attempts to single-handedly run the country are often met with large-scale protests — like in 2011-12, when tens of thousands of people took to the streets following Putin’s announcement to return to the presidency for the third time and reports of mass rigging of a parliamentary election.