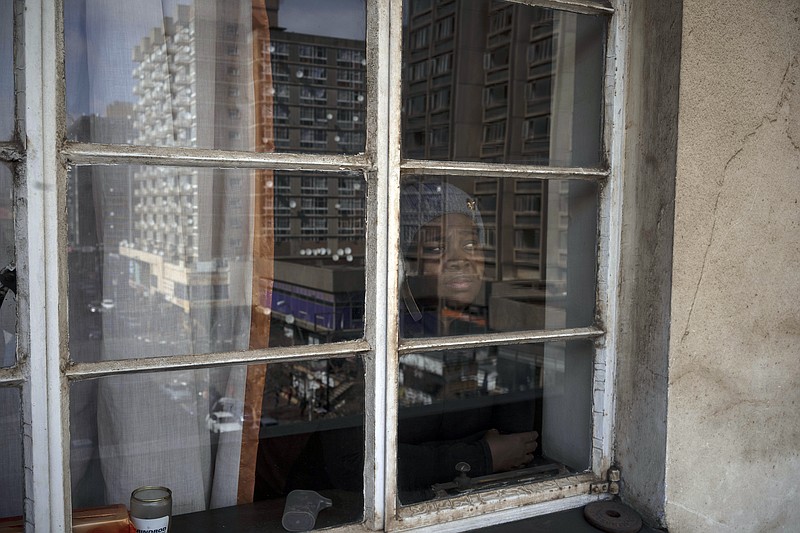

JOHANNESBURG (AP) - When her regular clinic ran out of her government-funded HIV medications amid South Africa's COVID-19 lockdown, Sibongile Zulu panicked. A local pharmacy had the drugs for $48, but she didn't have the money after being laid off from her office job in the shutdown to slow the spread of the coronavirus.

Desperate for the lifesaving medication, the single mother of four called a friend - a nurse with a local charity helping people with HIV, the Sister Mura Foundation. She's one of the lucky ones: Since April, the foundation has provided Zulu with the drugs, purchased locally.

Across South Africa and around the world, the pandemic has disrupted the supply of antiretroviral drugs, endangering the lives of more than 24 million people globally who take the medications that suppress the HIV virus.

In sub-Saharan Africa alone, a study by UNAIDS found a six-month disruption of antiretroviral therapy could lead to 500,000 additional AIDS-related deaths.

The disruptions are particularly troubling in South Africa, which has 7.7 million HIV-positive people, the world's largest number, with 62 percent of those depending on the government's antiretroviral program, also the world's largest. Anti-coronavirus restrictions have hindered imports of the drugs and the local production and distribution of the medications, according to a report by UNAIDS.

In addition, many HIV patients have stopped going to the often-crowded clinics for fear of being exposed to the coronavirus. And others cannot afford the transport fares to reach clinics.

In June, UNAIDS Executive Director Winnie Byanyima said countries should "urgently make plans now to mitigate the impacts of higher costs and reduced availability of antiretroviral medicines."

"I call on countries and buyers of HIV medicines to act swiftly in order to ensure that everyone who is currently on treatment continues to be on it, saving lives and stopping new HIV infections," Byanyima said.

HIV positive people who contract COVID-19, are more than twice as likely to die from the disease as people without HIV, according to an early study of mortality rates in South Africa's Western Cape province, the country's first epicenter for the disease.

"We're worried that we're going to be seeing an increase in deaths in co-infections such as TB and other opportunistic infections," said Dr. Nomathemba Chandiwana, an HIV research clinician.

Clinics in central Johannesburg have seen a 10-25 percent drop in people coming for HIV treatment, she said. On top of that, several clinics had to close temporarily when nurses and doctors became sick with COVID-19.

"Some clinics see 60-80 patients per day, so when one closes, for even a week, it means many people are not getting their drugs. It's a serious threat," said Chandiwana, who works for Ezintsha, part of the University of the Witwatersrand.

COVID-19 is similarly disrupting vaccinations. The past few months have seen a 25 percent reduction in childhood immunizations, said Shabir Madhi, a professor of vaccinology at the same university, who warned of possible outbreaks of measles.

The diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis also has also been hampered by the pandemic, risking the lives of many of South Africa's neediest citizens, health experts said.

"Disruptions to these medications is a public health problem. It threatens the poor and most vulnerable," said Vinyarak Bhardwaj, deputy director of Doctors Without Borders' program in South Africa, which has HIV programs in the Western Cape and KwaZulu-Natal provinces.

"We're responding to this threat by helping to minimize shortages and by providing stable HIV patients with multi-month prescriptions to limit their visits to the clinics. We're also increasing treatment advice by telephone and the internet," he said.

Reliable supplies of antiretroviral drugs are so critically important in South Africa, a monitoring program, Stop Stockouts, was created in 2013 and is closely tracking and responding to the disruptions amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

The mill town of Ngodwana in the country's northeast, a truck stop on the highway to Mozambique, is a microcosm of South Africa's inequality, rated as the world's highest.

Ngodwana's 3,500 residents are living in a densely packed shantytown, with limited electricity and running water. Safe distancing is nearly impossible. Years ago, the truck traffic was blamed for bringing HIV to the area; now come fears it will become a hotspot for COVID-19.

Many in Ngodwana can no longer afford to travel the 25 miles to the town of Nelspruit to get their drugs and don't feel comfortable going to the crowded local clinic, so the Dutch-based aid group North Star Alliance has set up a tented drop-in center and started home visits.