Missouri has for years ranked near the bottom among states for the number of women who die during pregnancy or within a year of giving birth.

Data has shown Missouri has a maternal mortality rate of about 25.2 mothers' deaths per 100,000 live births.

It's a condition that has given rise to the development of a Pregnancy-Associated Mortality Review Board, which produces annual reports about the data. In 2022, the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services (DHSS) initiated a Pregnancy-Associated Mortality Review Dashboard , which provides some insight into factors involved in maternal deaths.

However, despite generating conversations, the data -- and Missouri's poor showings -- have done little to urge lawmakers to push for an effort to improve outcomes.

Until now.

During Wednesday's State of the State address, Gov. Mike Parson called for lawmakers to include more than $4.3 million in the state budget to "implement a new maternal morality prevention plan to provide support and address preventable deaths of expecting and postpartum mothers."

The money would be available to make improvements to women's health in the state now because Missouri has billions of dollars in surplus revenue.

Martha Smith, Missouri's Maternal Child Health director, said the state has been in discussion for a long time about what strategies it should be implementing, should it ever have the funding, to address maternal mortality -- and significantly reduce it.

"How could we use funding to most effectively impact our mortality picture and standing in Missouri, and decrease that mortality rate?" Smith asked.

She said there is a federal goal of reducing maternal mortality by 50 percent. Smith added she would like to see the state also reduce its rate by 50 percent.

"I think that's a good goal for Missouri to have," she continued. "It'll take work. And it'll take funding. And it'll take time. It didn't get this way overnight, and it's not going to be fixed overnight, but we have to start somewhere."

DHSS requested the new funding to transform the quality of health services provided to women during and after pregnancy to reduce maternal mortality, according to Lisa Cox, director of communications.

"Missouri's current maternal mortality rate ranks among the worst in the nation, and an average of 61 Missouri women die each year while pregnant or within a year of pregnancy," Cox said.

Cox said DHSS proposed funding across five domains to improve maternal health:

• Develop and implement standardized maternity quality care protocols.

• Develop a perinatal health access collaborative to better reach underserved areas.

• Bolster the maternal care workforce.

• Optimize postpartum care to meet current gaps in care.

• Improve maternal health data including a state maternal child health dashboard.

Only six states had higher mortality rates than Missouri's 25.2 mothers' deaths per 100,000 live births. The states and their rates are: Georgia, 46.2; Louisiana, 44.8; Indiana, 41.4; New Jersey, 38.1; Arkansas, 34.8; and Texas, 34.2.

By contrast, the states with the lowest maternal mortality rates were: California, 4.5; Massachusetts, 6.1; and Nevada, 6.2.

What else can be done?

"We've been looking for some time at what other states that have had success are doing. And we want to be evidence-based on our approaches," Smith said. "We want to base our strategies on what evidence shows works."

If more local or regional programs around the state have worked, how might Missouri expand on those across the state? she asked.

The funding, if approved, probably won't cover everything health leaders would like to do, Smith said. But it will give them a good start.

The state can use that funding to help leverage other partners, like the federal government and nonprofit foundations to create more of a statewide approach to reducing maternal mortality.

Adam Searing, associate professor at the Georgetown University McCourt School of Public Policy's Center for Children and Families, said determinants of health, particularly for Black women, need to be addressed long before a woman gets pregnant before real changes to maternal mortality can be accomplished.

He added Missouri may have already taken steps that will -- in time -- reduce its rate of maternal mortality.

"The interesting thing for Missouri is that one of the main things you can do just happened -- which is expand Medicaid," Searing said. "It was delayed, but got done. It's going to be a few years before you see results from that."

Voters in 2020 passed Medicaid expansion through the initiative process, with the intent to expand the program to an estimated 275,000 people who make less than 138 percent of the federal poverty guideline. However, citing a loophole, the Republican supermajority in the General Assembly refused to fund the extended program until the Missouri Supreme Court ordered the state to fund it.

That order came in August 2021.

Critics have since said enrollment in the program (Mo HealthNet in Missouri) has been slow.

But through Medicaid, more women of childbearing age are receiving access to pre- and post-pregnancy treatment, Searing said.

"They can be healthier, even before they get pregnant," he continued, "in order to have a healthy pregnancy. After, it's really important for women to maintain that coverage because they may have a lot of problems with their health after pregnancy."

Hurdles to overcome

Smith said poor health outcomes are cyclical. She said that in order to have a healthy population, communities have to have healthy mothers having healthy babies -- who then grow up to become healthy mothers.

The feds gave states the opportunity to extend Medicaid coverage for women for a year postpartum during the pandemic. Missouri is one of several states that did not do so. Since then, the federal government has offered to allow states to continue offering year-long extended coverage, Searing said.

During pregnancy, and postpartum, some women may be at-risk of depression, high blood pressure and other conditions that worsen.

The Missouri Pregnancy-Associated Mortality Review Board's report looked at deaths in the state over three years -- 2017-19. It found, among other things, that Black women were more than three times as likely to die within a year of being pregnant as white women. The greatest proportion of pregnancy-related deaths occurred between 43 days and one year after pregnancy.

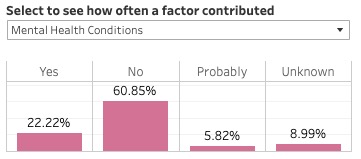

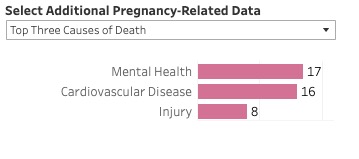

Mental health conditions were the leading underlying cause of pregnancy-related deaths, followed by cardiovascular disease. All pregnancy-related deaths due to mental health conditions were determined to be preventable.

The most common means of fatal injury for pregnancy-related deaths was overdose/poisoning.

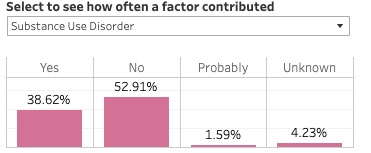

And substance-use disorder contributed to 32.7 percent of the deaths.

"The other thing that can help -- there is some more (federal) money for maternal mental health screening programs," Searing said. "Mental health is really a concern -- especially depression. That's something a lot of women really struggle with (during pregnancy and postpartum)."

There is no magical solution, he said.

DHSS's requests reflect several items from the review board's recommendations included funding for a statewide perinatal quality collaborative, increased availability of mental health screenings, empowering pregnant and postpartum women to engage through home visits.

There are programs that connect women who have been pregnant and had children with new moms. They visit the new moms and provide advice, Searing said.

"That's really important intervention," Searing said.