Four months ago, the Missouri Department of Corrections banned all physical mail to inmates in an effort to stymie the introduction of drugs into prisons.

Yet records from the department show overdoses in Missouri prisons aren't decreasing, and people who live in or work at prisons say guards smuggle in most contraband.

Starting June 15, thousands of people in Missouri prisons stopped receiving letters and photos in the mail. Following the lead of other states like Texas and Pennsylvania, Missouri started paying Texas-based company Securus Technologies to scan inmates' mail and send digital copies for viewing on electronic tablets issued to inmates when they enter the prison system.

On these tablets, incarcerated people can receive emails, video grams and photos, said Karen Pojmann, communications director for the Missouri Department of Corrections.

The tablets are provided by JPay, a subsidiary of prison telecommunication giant Securus Technologies, which profits off inmate purchases of games, e-books, music and stamps for email communication.

At the time of the policy change, state DOC officials said the move was necessary to stem the flow of drugs and other contraband into prisons.

"It's dangerous for the offenders inside the facility. And it's dangerous for staff. We're just trying to reduce one of the ways that harmful contraband enters prisons," Pojmann said.

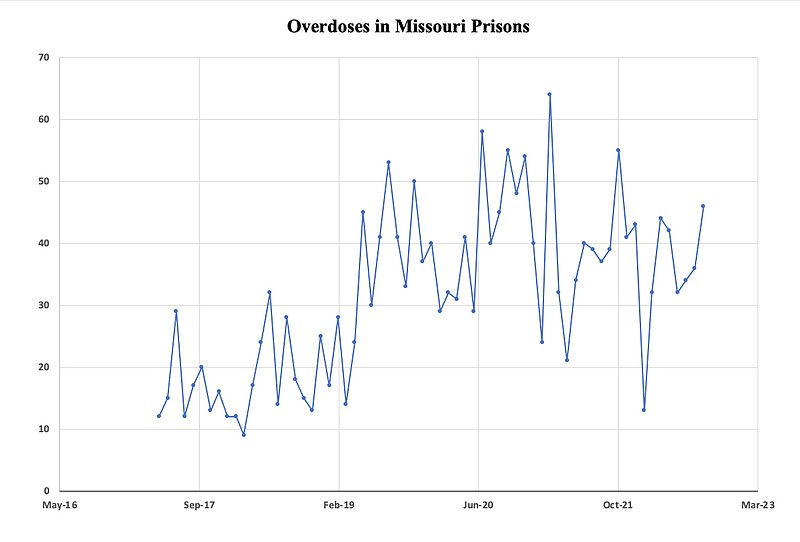

Prior to the ban on physical mail, overdoses averaged 31 people per month, according to overdose department records starting in 2017, which were obtained by Lori Curry, executive director of the advocacy group Missouri Prison Reform.

Between July and September this year, overdoses remained the same or increased, averaging 37 overdoses per month.

Curry, who regularly communicates with incarcerated people in Missouri prisons through Securus Technologies, was taken aback when she received the September numbers. A total of 46 people overdosed in Missouri prisons, the largest number in any month all year.

Pojmann said not enough time has passed to determine whether the mail policy will be successful in curbing overdoses.

'A piece of paper'

Travis Canon received his first scanned, digital letter at the end of June. Canon is incarcerated at the Jefferson City Correctional Center, and as it stands now, he's never leaving.

Canon was a teenager when he got hooked on drugs, and he was 19 when he committed his first serious crime. In 1997, Canon and two accomplices robbed a convenience store on U.S. 71 near Maryville. He shot and killed store clerk Gracie Hixson in the process.

Faced with a possible death sentence at 21 years old, Canon took the advice of his attorney, pleaded guilty to first-degree murder and started serving a life sentence without the possibility of parole.

The first two digital letters he received after the mail policy change were from a pen pal Canon has been writing for months. The third was from a friend of Canon's.

"There is something about a physical letter," Canon said in a message through Securus Technologies. "Maybe it is silly, but it feels like there is more of a connection to a piece of paper that your loved one held and wrote on. It is more personal and sentimental."

Amy Breihan, co-director of Missouri's MacArthur Justice Center, said, "It's just so dehumanizing. Not only is mail delayed, but there is something special about being able to hold in your hands a handwritten letter from your spouse or a drawing from your kid. That is just a lot more meaningful to people than scanned images on the tablet."

Every winter, the center sends out holiday cards to its clients. Breihan said they've decided to stop doing that this year due to the policy.

Canon said the new mail system has doubled the amount of time it takes for the letters to reach him. Before it used to only take a few days; now it takes a week, he said.

Legal mail is an exception to the mail scanning policy, which should still be sent directly to the facility where the offender is being held, Pojmann said.

But Canon claims many of his peers' legal correspondences are appearing digitally through JPay.

"If someone sends legal mail to the processing center, instead of to the facility, that's the mistake on the part of the attorney," Pojmann said.

Through it all, Canon has questioned what will happen if the department decides to change tablet service providers or get rid of them completely.

"What will happen to all of the personal emails and important correspondences?" he wondered.

Pojmann said all of that data stored on the tablet can be given to an offender on a flash drive upon release.

Months ago, when Curry wrote about the change on the Missouri Prison Reform blog, many responded to her with concerns that inmates do not always have access to electronic devices like tablets, particularly those in solitary confinement.

Curry says that many concerns are rooted in frustration about how inmate email had already functioned.

"So many photos and videos don't make it to the incarcerated, and there's no reason given," Curry says. "Pictures of people's kids at Christmas, completely dressed and out in public. Things that are innocent and should absolutely get through. Securus blames the prisons. The prisons blame Securus."

Canon said the department has consistently blamed the internal presence of drugs on mail and visits. Visitations were shut down during the COVID-19 outbreak, but overdoses generally rose during the pandemic, according to the department's records.

That's when he started hearing mail was supposedly the real problem, Canon said.

He added the policy essentially punishes prisoners for drug presence in prisons when the majority, he claims, are coming through staff.

"I know a shell game when I see one," Canon said. "Sometimes when there is a problem, and you can't find the source of it, the best place to look is in the mirror."

'Just once is enough'

Breihan filed a Sunshine Law request for records justifying the new mail policy and communications about it as the policy was enacted.

Nowhere in the contract with Securus Technologies and in the email exchanges that Breihan received could she find any evidence showing drugs frequently entered prisons through the mail.

Pojmann said the department doesn't have accurate data on how frequently drugs are introduced through the mail. Often those drugs aren't found until they're already inside the prison, so it's difficult to trace where they came from.

Tim Cutt, director of the Missouri Corrections Officers Association, said it's widely understood within the department that mail is just a small segment of how drugs enter into prisons.

He said he has seen instances where fentanyl had been infused into printer ink and crayons or soaked into the page.

Though mailroom workers who used to handle inmates' physical mail would wear gloves to protect themselves from potentially coming into contact with substances, Cutt said a mailroom worker had been hospitalized from exposure to fentanyl.

"Even just once is enough to justify the policy, in my view," Cutt said.

Digital mail was also intended to cut down on mail-related work that was assigned to corrections officers. The Missouri Department of Corrections has been undergoing a severe staffing shortage, which prison administration hoped the transition away from physical mail would help alleviate.

Cutt acknowledged the primary channel that drugs enter Missouri prisons through is staff.

Cutt said there have been many instances where Corrections employees have been caught bringing drugs in. Those employees are terminated, and depending on the circumstances, prosecuted for introducing contraband into a correctional facility. He said there are several cases being litigated.

"If inmates' main point of contention is that it's not the real letter, to me it doesn't matter. It's going to make it a little bit safer. Even though it's only a little bit, it still counts," Cutt said.

Pojmann said, "What we're doing is eliminating one of the ways drugs can get into a facility. I don't see why anyone who's concerned about the safety and well-being of people in our facilities would be opposed to eliminating one of the ways that harmful and possibly deadly drugs can get in."

'Red flags'

Criminal justice reform advocates like Breihan have warned the policy could violate inmates' privacy and further isolate them from their loved ones.

Breihan is looking for further clarity on what happens to the data aggregated from incarcerated people's mail stored in Florida where the mail is scanned.

According to the Department of Corrections' contract with Securus, the company keeps the physical mail for 45 days until it's discarded. If the sender wants that letter back, they can request it to be returned.

Before the scanned copy is sent to people in Missouri prisons, Pojmann said the department looks through the messages to censor any content they don't allow offenders to receive.

Breihan said this procedure indicates the data Securus keeps is text searchable.

"If they're keeping copies of every single letter that goes to every single prisoner, and that information is text searchable, then there's like a significant amount of data surveillance going on, which raises red flags."

An article from The Marshall Project examined a similar mail policy change in Texas enacted in 2020. The Texas Tribune and The Marshall Project's investigation found the switch to digital mail had no meaningful impact on the drug trade in Texas prisons.

Pennsylvania's Department of Corrections was among the first to restrict traditional physical mail, in 2018. Since then, more facilities have implemented bans on physical mail in recent years, including many in the last year alone such as Florida, New Mexico and North Carolina.

Pojmann said the department considered the successes and mistakes of other states in implementing their version of the policy.

Breihan said if Securus Technologies and other private companies monitoring incarcerated people's mail are aggregating data that is intrusive, there could potentially be a Fourth Amendment claim against them. The Fourth Amendment protects people from unreasonable searches and seizures by the government.

But legal challenges against prison administrations are difficult, she said.

"The courts give prison administrators a lot of deference in addressing security concerns."

The story has been updated to clarify only the tablets are provided free to the inmates; they pay for stamps, to watch videos and to play games. The story was also updated to state that Pojmann said the department can't conclusively determine how drugs end up in prison.