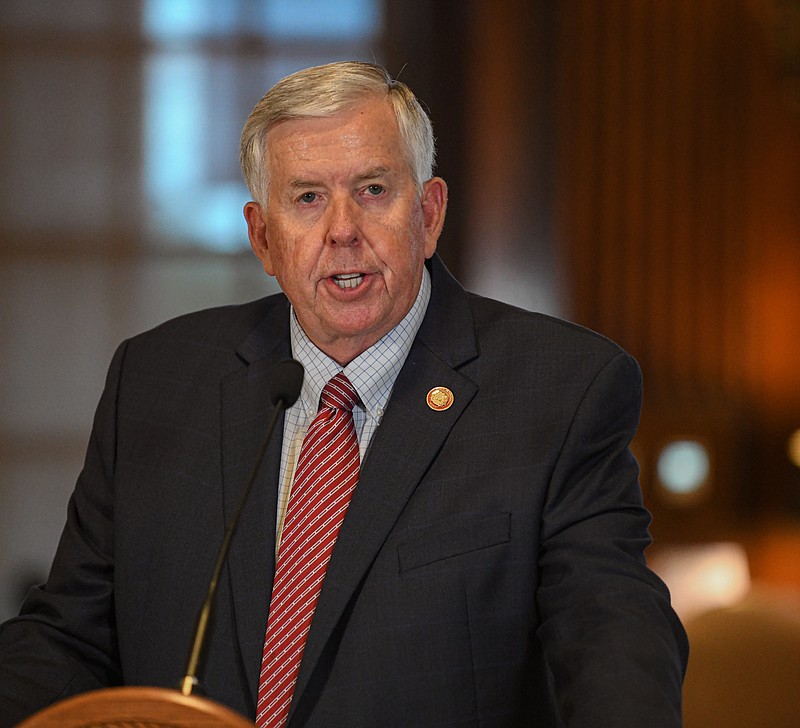

More mental health resources, not more gun laws, are needed to prevent gun violence like what occurred at a St. Louis school recently, Missouri Gov. Mike Parson said in response to media questions last week.

But in the last legislative session, lawmakers submitted 25 bills intended to improve mental health services in the state.

Only three were signed into law.

Most never left committee assignments.

The problem, state mental health officials say, is complex issues are rarely solved by simple solutions.

On Oct. 24, former student Orlando Harris, 19, burst into the Central Visual and Performing Arts High School and shot a teacher and a teenager. Seven others were injured before police stormed into the building, confronted the gunman and killed him.

The Missouri Department of Mental Health released a statement Friday afternoon focused on the mental health concerns Parson raised in statements days after the shooting.

"Every mass shooting event is tragic on many levels with effects impacting individuals, families and whole communities," the statement began. "While news stories often link such violence with mental illness, it is important to remember that, statistically, individuals with mental illness are more likely to be victims of crime than perpetrators of crime. Acts of violence often represent the culmination of many factors, and complex issues are rarely solved by a single or simple solutions."

Tragic events serve as reminders that mental health should be prioritized as much as physical health, according to the DMH statement.

Mental health concerns should be addressed early -- and continue to be monitored for a lifetime, it stated. Each person has different experiences, it continued. Trauma, suicide, depression, anxiety and substance use affect many lives.

"Determining how to address these problems can seem overwhelming, but it's important to recognize that a variety of interventions can be effective," it stated.

Interventions underway now

Following Parson's comments, the News Tribune reached out to the Governor's Office for clarification on what kind of mental health policies and funding he supports.

Kelli Jones, a spokeswoman for the governor, responded with actions the state has taken since Parson formed a School Safety Task Force in the wake of the 2018 Parkland, Florida, school shooting, ongoing state actions and themes from state leaders.

School leadership taking the possibility of threats seriously is a major theme from state leaders, Jones said, as is promoting a culture where students and teachers feel comfortable reporting threats. Other talking points emphasize the role relationships between law enforcement and school districts can play during and after incidents occur and that the "root issue behind human-caused safety threats on school campuses are behavioral health issues."

The School Safety Task Force began meeting again this summer to coordinate efforts around school safety, Jones said. The state has also increased funding for the Department of Public Safety to address school security and student mental health needs, and the Missouri School Board Association is developing an app for schools to implement Emergency Operations Plans and share them with law enforcement agencies.

Under way is a requirement for all schools to develop and implement Emergency Operations Plans and review them annually, she said. School personnel are to receive school safety and violence prevention training as well.

Missouri's budget this fiscal year includes: $2.5 million for a school safety program DPS is bidding out; $1.9 million for a statewide program that allows schools to directly alert 911 services of an incident through an alert system DPS manages; $1 million for school safety programs and behavioral health services -- an increase from the typical $300,000 contract the state has with the Missouri School Board Association to provide the training; and $100,000 for a mental health coordinator at the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education.

The federal Bipartisan Safer Communities Act, signed into law in June, provides the state additional funding for mental health professionals and services, school security officers and other resources for improving school security.

Additionally, districts conduct vulnerability assessments to improve security measures and have trained behavioral assessment teams to address student mental health concerns and "safety incidents," Jones said. The Courage2Report hotline offers a confidential way to report school violence concerns.

A change in culture called for

Rep. Rudy Veit, R-Wardsville, pointed out people oftentimes don't see many warning signs of mental illness until it's too late. He warned that violence in children's video games must be monitored.

"Make more efforts in schools to keep people aware of symptoms," Veit said. "We do need to have a little more awareness, and classes for kids -- if they have mental illness problems to be willing got speak about it."

Problems need to be addressed sooner, he said.

Veit said folks need to get beyond the stigma surrounding mental illness. For years, if people had mental illness issues, they were considered "not a good person."

Too often, when a child is depressed and someone asks what's wrong, the response is "Nothing," he said.

There are conversations that lawmakers need to have about addressing mental illness in schools, he suggested. However, every school should be left to determine how or what it needs concerning mental health, he said.

The DMH statement called for expansion of focus on early prevention and mental health promotion. It said early prevention offered alongside increased access to treatment services for people already demonstrating mental health concerns "is crucial."

"Prevention efforts, particularly among school-age children, can help youth develop protective factors that can increase their resiliency, learn healthy coping strategies, and gain access to positive supports," it stated.

Prevention efforts include education and early intervention activities provided for children, youth and families, according to the DMH.

"These services offer structured programming and/or a curriculum with multiple sessions, including pre- and post-testing and identifying risks and protective factors," the DMH statement said. "These programs and services also have a variety of activities, including informational sessions and training/technical assistance with groups."

Big Brothers Big Sisters, which provides mentoring to youths, is an example of a direct prevention and early intervention program, according to the department.

Missouri Alliance of Boys and Girls Clubs is another. The alliance provides youths with the opportunities to participate in life-enhancing experiences in five broad domains: character and leadership development, education and career development, health and life skills, the arts, and sports, fitness and recreation.

"Evidence-based school programs can be offered to larger numbers of youth to help build their skills to manage stress and difficult life circumstances," the DMH statement said.

Evidence-based prevention programs are being used in various parts of Missouri, DMH officials said.

They include: Too Good for Drugs; Too Good for Violence; the Second Step curriculum; Skills Mastery and Resilience Training (SMART) Moves and Meth SMART; PeaceBuilders; Positive Action; and the Strengthening Families Program.

DMH added that youth Mental Health First Aid (MHFA) helps adults or peers learn about signs of mental health concerns and how to help someone who may be experiencing them. This program has trained several districts of educators and school administrators to recognize signs.

Also, Signs of Suicide is a specific evidence-based practice that addresses suicide prevention in schools. Signs of Suicide, along with MHFA, and several other of the above prevention programs are offered through Jefferson City schools.

Mental health bills stall in Legislature

The Missouri Legislature has had opportunities to offer additional mental health resources as recently as this year. Some lawmakers had in fact asked for more behavioral health resources, during a legislative session in which the state was fat with COVID-19 recovery funding.

But the Legislature may have dropped the ball.

Lawmakers submitted 25 bills intended to improve mental health services in the state, including several aimed at providing services for school-age children; only three were signed into law.

Most of the bills never left committee assignments.

HB 3010 was a regular budget bill providing appropriations to the Department of Mental Health, and HB 2116 mentions mental health facilities among health care providers who can't limit visitor access to patients.

SB 681, sponsored by Shelbina Republican Sen. Cindy O'Laughlin, is an education bill with two provisions related to mental health. The bill requires school districts to print the 988 suicide hotline on student IDs and requires "mental health awareness training" for public high school and charter school students at any time during their four years of high school. The mental health education, decided by districts based on a program created by the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education, is rolled into existing health and physical education curriculum.

Democratic St. Louis Sen. Karla May's Senate Concurrent Resolution 27 sailed through her chamber, then reached the House, where it floundered. The resolution recognized a need for mental health awareness training for high school students in public schools and charter schools.

Rep. Dave Griffith, R-Jefferson City, said a number of lawmakers offered legislation in the 2022 legislative session that would affect mental health services for students.

"Dealing with mental health issues is of grave concern for me and for my colleagues," Griffith said. "Providing more funding to (Missouri Department of Mental Health) and looking at ways we can support local communities with their mental health issues is something I am sure will be something we will discuss again in the coming session as it has been for the four years I have been in the House. Senator May's bill was voted Do Pass and it addressed some but not all mental health problems."

May's bill was voted "do pass" in the House's Health and Mental Health Policy Committee, then again in the House's Administrative Oversight Committee. But it was never allowed to be discussed on the House floor.

Another of May's bills, Senate Bill 1057, would have established mental health awareness training for students in schools and charter schools. That bill passed the Senate Education Committee, but was never heard on the Senate floor and was eventually folded into SB 681.

Also among a list of bills Griffith pointed out were: House Bill 2019, which would have provided a state supplement for public schools to hire a school nurse and a mental health professional; House Bill 2342, which would have allowed minors to seek out mental health services; and House Bill 2767, which would have required school districts to excuse students with behavioral health concerns from attendance at school.

All received committee assignments.

None were heard in their committees.

Sen. Mike Bernskoetter, R-Jefferson City, said he agrees with the governor's position that guns are not to blame for the rise in school shootings, but issues surrounding gun deaths are complex.

"Mental health plays a part, but frankly I think our culture plays a large part," he said. "The rise of social media has done as much to isolate people as it has to connect them. Coupled with the isolation people experienced during COVID, I think there is a growing disconnection between people and their communities."

Bernskoetter urges for a change in culture -- which he said starts at home, school, church, the Capitol and "everywhere" -- and a revitalization of community relationships. He didn't offer specific policy the state could enact to address mental health and gun violence in schools.

Bernskoetter said he would be willing to consider any bill that would address mental illness, but they shouldn't be the end goal.

"There may be changes we can make to help the mentally ill before they get to the point they become homicidal. I am willing to consider any bill that might help the mentally ill, and willing to listen to the arguments for more mental health funding or for more officers," he said. "However, those are steps to alleviate the symptoms, not eliminate the cause. I think we ultimately have to look at ourselves and realize that we are dehumanizing each other. That has to stop."

Resources available today

Several resources are already available to help families and schools out, the DHS statement said.

"For youth already experiencing mental health problems, ready access to services is important," it said.

Opportunities to enhance behavioral health services, the statement said, include raising awareness about 988 -- the behavioral health crisis line, increasing the number and scope of behavioral health crisis centers, supporting staffing needed to deliver mobile crisis response, developing longer-term crisis stabilization options once hospitalization is no longer appropriate, and expanding support for the newly developed Youth Behavioral Health Liaisons (who assist school personnel in understanding, managing and addressing behavioral health issues of students who are not already connected to services or providers and who come to repeat attention of school personnel).

These liaisons can help divert youths from unnecessary or prolonged hospitalizations.

Youth Behavioral Health Liaisons were launched just months ago. The liaisons work with local systems to coordinate care for youths experiencing behavioral health crises.

"Schools and juvenile facilities, along with other child-serving systems, can access the YBHLs and benefit from this level of coordination," DMH said. "YBHLs work within Certified Community Behavioral Health Organizations and in some other community mental health and substance use disorder treatment agencies.

Missouri's General Assembly funded four liaisons last fiscal year -- two in Kansas City and two in St. Louis.

Twenty-seven more are supported through time-limited federal funding. A map of YBHL Points of Contact for Missouri counties may be found at https://dmh.mo.gov/media/pdf/missouri-map-ybhl-poc-counties.

"Missouri has been fortunate that policy-makers have shown support for such efforts and recognize the importance of expanding access to mental health services," the DMH statement said.