If the world were fair, family members caring for people with Alzheimer's disease would be well compensated.

But, it's not.

Within its report titled "2022 Alzheimer's Disease Facts and Figures" the Alzheimer's Association details the challenges caregivers face when assisting people suffering from the disease.

In this third installment of our look at Alzheimer's disease, the News Tribune will examine caregiving for dementia patients and the unique obstacles those caregivers have to overcome.

Caregiving may include offering several levels of assistance for patients -- providing emotional support, coordinating care, daily activities, or even bathing and dressing.

The report compares caregivers of people with dementias with caregivers for people with other medical conditions.

Becoming a caregiver takes a deep investment of love, said Lois Long, a Fulton/Columbia-area volunteer and advocate for caregivers and people with dementia. Long reminds readers that dementia describes the symptoms associated with numerous conditions.

Long said her father had dementia and her brother, who had Parkinson's disease, recently died.

There are multiple things that happen when a caregiver becomes a 24-7 person responsible for keeping dementia patients safe, she said.

Some patients tend to wander.

"You turn your back, and maybe he's out the door," Long said.

There are devices available to help keep track of patients, she added. So, caregivers should keep those in mind.

Why offer care?

According to biomedcentral.com (a portfolio of peer-reviewed medical journals), in 2021, the most common reasons caregivers provided assistance to a person with Alzheimer's or other dementia were:

• The desire to keep a family member or friend at home (65 percent of survey responses).

• Proximity to the person with dementia (48 percent of responses).

• Caregiver's perceived obligation to the patient (38 percent).

"Caregivers often indicate love and a sense of duty and obligation when describing what motivates them to assume care responsibilities for a relative or friend living with dementia," the report states.

They oftentimes become unpaid caregivers.

Folks outside nursing facilities living with dementia are most likely to rely on multiple unpaid caregivers, who are often family members. Thirty percent of older adults with dementia rely on three or more unpaid caregivers, according to the Alzheimer's report. Only 23 percent without dementia do so.

"Only a small percentage of older adults with dementia do not receive help from family members or other informal care providers (8 percent)," the report states. "Of these individuals, nearly half live alone, perhaps making it more difficult to ask for and receive informal care."

About half of caregivers for spouses with dementia and near the end of life provide care without the help of any other family members or friends, it says.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 80 percent of people with Alzheimer's disease or related dementias receive care in their homes.

All this unpaid care adds up.

More than 16 million Americans provide unpaid care for someone with dementia. It's estimated that in 2021, they provided 17 billion hours of unpaid assistance, according to the CDC. The value of the assistance is about $271.6 billion.

There are about 194,000 caregivers throughout Missouri. It has been estimated they provide about 292,000 hours of unpaid care annually, according to the Alzheimer's Association report.

The caregivers

Multiple organizations have conducted studies to show what family members are caring for loved ones suffering with dementia.

According to the Alzheimer's report, they have found:

• About two-thirds of dementia caregivers are women.

• About 30 percent are 65 or older.

• More than 60 percent are married, living with a partner or are in a long-term relationship.

• More than half are providing care for a parent or in-law.

• About 10 percent provide help to a spouse with dementia.

• Among primary caregivers, more than half take care of their parents.

• About one quarter of dementia caregivers not only care for an aging parent, but also for at least one child.

• Two-thirds are white, 10 percent Black, 8 percent Hispanic and 5 percent Asian American.

All that said, responsibility of caring for a loved one with dementia most often falls to women.

The Alzheimer's report shows about two-thirds of dementia caregivers are women. Furthermore, more than one-third of caregivers are daughters.

The Alzheimer's association conducted a poll in 2014 that found two-thirds of people who provided care for 21 hours per week or longer were women. Another study determined of all dementia caregivers who provide care more than 40 hours per week, 73 percent were women.

Women were also far more likely to live full time with a person with dementia than men.

"Caregivers who are women may experience slightly higher levels of burden, impaired mood, depression and impaired health than caregivers who are men, with evidence suggesting that these differences arise because female caregivers tend to spend more time caregiving, assume more caregiving tasks, and care for someone with more cognitive, functional and/or behavioral problems," the report found. "Among dementia caregivers who indicated a need for individual counseling (85 percent) or respite care (84 percent), the large majority were women."

Public help

The University of Minnesota School of Public Health announced in 2020 that with support from the CDC, it would establish the Public Health Center of Excellence in Dementia Caregiving. Since its creation, the center has striven to "recognize and elevate the essential role informal, unpaid caregivers having in caring for people living with dementia, and the many benefits they bring to our communities -- from reducing the need for paid services, to allowing people who need assistance to remain longer in their homes to serving as a bridge between health care and social services," according to its website, bolddementiacaregiving.org.

The center doesn't provide direct services to caregivers, but allows them to use resources it provides through the site.

"The WeCareAdvisor study is evaluating whether use of an online tool (the WeCareAdvisor) can provide caregivers helpful strategies to manage dementia-related behavioral and psychological symptoms that in turn reduce stress and enhance confidence," the website states. "The WeCareAdvisor walks caregivers through an easy-to-use step-by-step approach to understand why dementia-related behavioral and psychological symptoms (such as agitation, restlessness, irritability, repeated questions or other behaviors) occur and provides strategies that are customized to the family's situation to help manage such behaviors."

An important consideration, Long said, is the health and well-being of caregivers as the disease progresses -- and their stress increases.

Caregivers may receive access to respite services by calling the helpline Alzheimer's Association offers a 24-hour helpline at 800-272-3900.

The Caregiver Relief Program in Missouri is handled through the Alzheimer's Association and the Missouri Rural Health Association.

"This gives caregivers caring for someone in the home access to be reimbursed as much as $700 per year for services and products," Long said. "Some of the people that I've helped spend all the money they get buying adult incontinence products."

Respite funding may help with that, or pays someone to come into the home, allowing the caregiver to go on their own appointments if necessary, or just to take a break.

What caregivers do

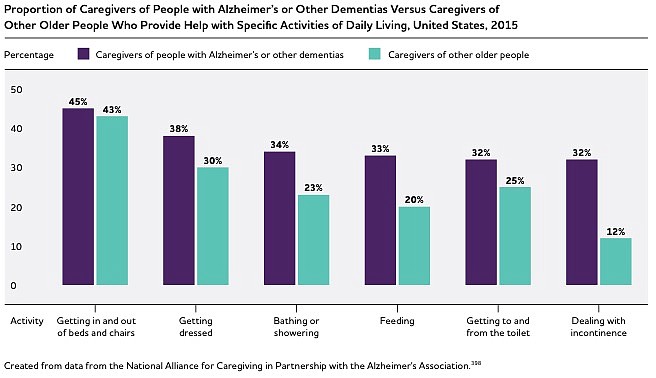

The 2011 National Health and Aging Trends Study showed caregivers of people with dementia (85 percent) are more likely than caregivers of people without dementia (71 percent) to provide help with self-care and mobility.

"The need for culturally responsive services and supports for people living with dementia and their caregivers is also pronounced," the Alzheimer's study said. "People living with dementia tend to have larger networks of family and friends involved in their care compared with people without dementia. Family members and friends in dementia care networks tend to provide help for a larger number of tasks than do those in non-dementia care networks."

Mostly, caregivers report positive feelings or outcomes about caregiving, such satisfaction from helping others or family togetherness.

Despite that, they also report higher levels of stress.

Twice as many caregivers of patients with dementia report substantial emotional, financial and physical difficulties than caregivers of people without dementia (about 60 percent rate the emotional stress as high or very high). And spousal dementia caregivers report increased burden over time, often caused by behavioral or functional changes in their patients.

"Many people with dementia have co-occurring chronic conditions, such as hypertension or arthritis," the Alzheimer's study said. It showed their caregivers were two to three times more likely to report emotional difficulties.

Another study found they were "significantly more likely to experience depression and anxiety than non-dementia caregivers.

"The prevalence of depression is higher among dementia caregivers (30-40 percent) than other caregivers, such as those who provide help to individuals with schizophrenia (20 percent) or stroke (19 percent)," it said.

Additionally, they experience depression and suffer from cognitive problems. Those who care for people with four or more behavioral problems (such as aggression or wandering) are most likely to report clinically meaningful depression and burden.

In many cases, admitting a relative to a care facility does little to improve the emotional well-being of family caregivers.

"Demands for caregiving may intensify as people with dementia approach the end of life. In the year before the death of the person living with dementia, 59 percent of caregivers felt they were 'on duty' 24 hours a day, and many felt that caregiving during this time was extremely stressful," the report states. "The same study found that 72 percent of family caregivers experienced relief when the person with Alzheimer's or another dementia died."

During the last year of a dementia patient's life, they relied on more hours of family care (64.5 hours per week) than people with cancer (39.3 hours per week).

Caregivers living with family members with dementia pay for about 64 percent of total care costs incurred during their family members' last seven years of life, the report found.

Resources are available to help people with Alzheimer's and other forms of dementia, Long said.

The Alzheimer's Association offers a 24-hour helpline at 800-272-3900. Caregivers may access consultations, information and referrals to support groups at alz.org.

More News

NoneRELATED

Editor’s note: This is part three of an occasional series on Alzheimer’s disease.

Previous coverage includes:

• Alzhemer’s disease afflicts 6.5 million Americans: https://bit.ly/3MrQj96

• Losing a loved one to dementia is slow, painful: https://bit.ly/3k7Gots

• Diagnosing issues behind memory loss can be challenging: https://bit.ly/3sB2Uzq

• Alzheimer’s care hasn’t changed much in decades: https://bit.ly/37JsvyP