A national three-digit hotline for suicide (and other crises) interventions will go live in July.

Just call 988.

The three-digit code -- 988 -- will replace the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, and give Missouri the chance to expand crisis services.

Seizing on the chance to connect people undergoing a crisis with services statewide, Gov. Mike Parson set aside $28.5 million in his proposed 2023 budget to not only implement the program, but connect hotline users with regional crisis call centers and crisis intervention teams.

The Federal Communications Commission in 2020 designated 988 as the national three-digit code for individuals experiencing a mental health crisis to contact a counselor. But, it's also a responsibility of each state to ensure the number is available in each community at any time, according to Casey Muckler, Missouri's 988 project lead.

Missouri has created a task force to prepare the state's plan -- and to prepare the rollout of the program, Muckler said.

"We want to make sure our crisis system is going to be equipped to handle the volume we expect," she said.

In 2020, Missouri had two crisis centers (Suicide Prevention Lifeline providers who answer calls to the 800 number), said Lauren Moyer, Compass Health Network vice president of clinical innovation.

Missouri put together a team to begin building capacity for its crisis centers, which already received more than 20,000 calls annually.

The state estimates it will receive more than 250,000 calls, texts and chats to the 988 code during its first year, at a cost of more than $11 million.

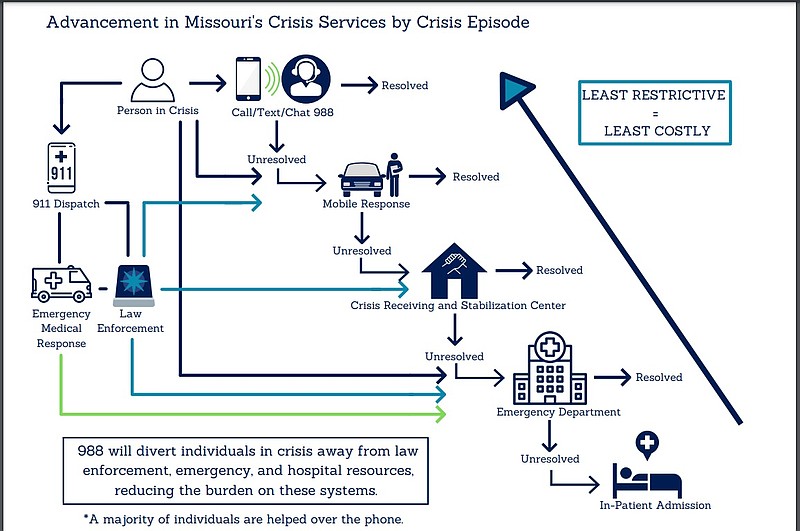

The 988 code provides an opportunity to divert those patients away from emergency rooms and encounters with law enforcement.

Missouri's top priority, according to the state Department of Mental Health (DMH), is to build enough capacity to ensure 24/7 statewide coverage to answer 988 calls, chats and texts for each of the state's 114 counties and the City of St. Louis.

Federal officials have told Missouri it is ahead of other states in implementing the code, Moyer said, in part because it has expanded its two call centers to seven.

"We've already secured some funding," she added. "(The governor included) a line item of about $28.5 million to support this crisis of care continuum we're trying to build."

The state is trying to get funding for staff and infrastructure, Moyer added.

The physical location of each call center doesn't really matter, she said, especially if the center can resolve the caller's issue.

"The follow-up piece is critical," Moyer said. "When we only had two providers, if you called and it was busy, (your call) would roll to a national back-up. That might be in California."

It was not conducive to being able to provide resources to callers.

The state now has seven call centers. And the national back-up is located at Provident Behavioral Health in St. Louis.

"All of our crisis call centers are working together to integrate and make sure our resources and services are working together. We meet monthly to build on those resources, and make sure they are shared," Moyer said. "What we are truly trying to create with 988 is a no-wrong-door integrated system of care."

Each of Missouri's counties will be covered by one of the seven 988 call centers. This will help the state reach rural areas of the state where complete coverage is more challenging, according to DMH.

The way the system works now, if a person undergoing a crisis dials 911, dispatchers have little choice but to connect them with law enforcement agencies or emergency medical responders.

If the community is lucky, it will have officers who have undergone Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) training available, to help prevent the patient from ending up in a hospital or jail.

In recent years, Missouri law enforcement officers and other organizations across the state have undertaken the CIT training (a partnership of law enforcement, mental health and addiction professionals, hospitals, individuals living with mental illness or addiction disorders, their families and other community advocates). They learn to identify issues, communicate with people they may come into contact with and connect them with community liaisons or other helpful resources.

Community mental health and substance use disorder liaisons are behavioral health professionals who work with clients who have frequent interactions with law enforcement and courts. Their focus is to direct people with behavioral health issues toward services they need -- and away from the justice system.

Parson requested, and the Legislature included in its 2022 budget, $15 million to establish six new crisis stabilization centers (known locally as crisis access points) and to further support five existing ones (like the Kansas City Assessment and Triage Center, Springfield's Burrell Behavioral Crisis Center, Joplin's Ozark Center and others).

The budget included $5.3 million to add 50 liaisons to the existing 31.

When the system goes live, if a patient were to call, text or chat to 988, the counselors they reach might be able to resolve their issue over the phone.

"We know that about 90 percent of 988 crisis calls can be resolved over the phone," DMH Director Valerie Huhn told media before Parson delivered his State of the State address Jan. 19. "Ten percent of those are going to require additional followup. We don't want that followup to be law enforcement. We want that followup to be trained (behavioral health) professionals. So, this investment in the 988 crisis response is really, really important."

All counselors receiving calls and engaging with clients are to go through a training curriculum that includes suicide prevention, risk assessment and intervention strategies based on Missouri-specific competencies and national best practices, according to the DMH.

Muckler said, "988 is just one piece for the crisis continuum that we're trying to create in the state of Missouri. We're just ensuring that we have the ability to cover the entire continuum of care -- 988, mobile crisis response teams and behavioral health centers."

If the counselor can't resolve an issue over the phone, he or she will dispatch one of the mobile response units for an in-person meeting.

"The next phase is to make sure we have someone who can resolve the situation if it can't be resolved over the phone," Moyer said. "Qualified mental health professionals will go into the community where the individual or family is experiencing crisis -- in their home or in the street."

If they cannot resolve the issue, the mobile response units will connect the patient with an access point for further efforts.

The access points, which have nursing staff on hand, may be able to provide medications. They are sites where patients may rest, take a shower, get a meal and watch television for up to 23 hours.

Jefferson City has one, known as a crisis access point, which is one of about 11 operating in the state.

The current budget would allow for 12 additional access points to open across the state.

"One thing that we're still trying to focus on and gain some additional clarity on is -- the FCC did pass text- and chat-to-988," Moyer said. "That is a whole new layer that we'll need to prepare for. It's a whole new layer, especially for our youth, who prefer to communicate that way."

Meanwhile, state organizers of the 988 rollout are exploring ways to help with behavioral health-related calls that come into 911 dispatchers, she said. Organizers are trying to set up some pilot opportunities to transfer some of those calls to a 988 provider.

"The bigger piece," Moyer said, "is that we're not giving people those long 800 numbers. Just call 988."