When Judge Sidna P. Dalton happened upon spear points, pottery shards and scraping tools on one of his many artifact hunts, he knew he had found something unusual.

"I noted that the material I was finding appeared so totally different in design from what I was finding elsewhere, I boxed it all up and sent it to the University of Missouri for study," he said.

Thus, the Dalton Culture was discovered. The judge had found a missing link in a prehistoric cultural timeline that had eluded archeologists.

Dalton took his unusual finds to Dr. Carl Chapman, an archeologist at the University of Missouri. Chapman confirmed what the judge suspected. The artifacts were indeed different. Chapman was secretary of the Missouri Archaeological Society at the time. In his long and legendary career, it was Chapman who discovered the co-existence of humans and the now-extinct mastodon (later confirmed by Russell Graham) suggesting humans have been in Missouri as far back as 12,000 B.C.

Chapman is now recognized as the dean of Missouri archaeology.

Archeologists had long recognized the four cultural periods of human habitation in North America: Paleo-Indian (12,000-10,000 B.C.), Archaic (8,000 B.C.-400 A.D.), Woodland (500 B.C .-1000 A.D.) and Mississippian (1000 A.D.-1500 A.D.). Transitions from one age to the next typically show a gradual shift in the sophistication of tools between the ages, sometimes overlapping, but archeologists saw an abrupt change between Paleo-Indian and Archaic. This gap now had a name; the Dalton Culture.

The Paleo-Indians existed near the end of the ice-age and hunted large mammals that became extinct around 10,500 B.C. With a changing environment, humans had to develop new survival strategies. The Dalton people were the first in North America to develop a heavy-duty stone chipped tool, the adze. With this multi-purpose tool, they could chop, cut, hoe and carve. The Dalton point, a hunting tool, was also distinctive of this period; fish-shaped and often serrated. Conquering their changing environment became easier.

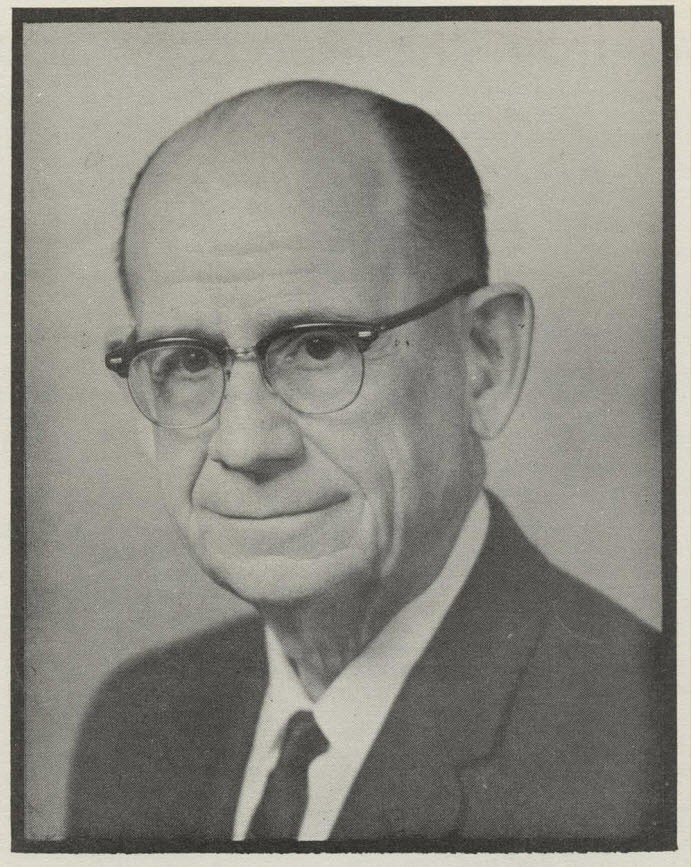

Sidna Poage Dalton (SP to his friends) was born in 1892 and was a brother to Missouri Gov.John Dalton (term 1961-1965). Judge Dalton's fascination with prehistoric artifacts began as a boy on the family farm in Vernon County, Missouri. "I dreamed of the hunters who no doubt lay in wait for deer ... of stone-age people that lived long before the dawn of recorded history," Dalton said.

When he was appointed to the Missouri Supreme Court in 1939, he brought his wife, Edna and their four children to Jefferson City, settling on Elmerine Avenue. Here in Cole County, his love of the hunt was reignited in earnest. His son, Andy, recalled a typical Sunday for his father consisted of lunch followed by a short nap. He then would ask who was going with him to hunt arrowheads. All of the family, including Edna, would often join him. His neighbors, Dr. Sparks and Guy Sone, were also hunting companions. Andy recalls it was his mother who found the largest spear point in the collection.

Dalton found thousands of artifacts over the years on more than 400 sites, mostly in Cole County, keeping meticulous records of where they were collected. His favorite sites were the recently cultivated farm fields.

"I never go on a man's farm without his permission and one of the joys of this hobby is the chance to visit with many fine farm people," he said.

Dalton's friend, Ed Buel, an avid collector, managed many farm loans at Central Trust and knew all the local farmers. It was a good fit.

The riverbanks of the Moreau and Osage rivers were other rich sources. Although burial mounds were abundant along the Missouri river bluffs in Cole County, Dalton was appalled by those artifact hunters who disturbed them.

It was in the mid-1940s that the Highway 50 bridge over the Osage River was being improved. This involved disturbing earth around the river's west bank. It was Edna's suggestion that this could be a good site for her husband to explore. She was right. It was here that Dalton recognized atypical artifacts. Carbon dating of charcoal found with the items showed they were almost 11,000 years old (9,000 B.C). Most prehistoric artifacts in this area date to the Late Woodland culture, about 400-1000 A.D.

"It was Carl Chapman who determined that Dalton's find was a distinct period of human development," said James Duncan, archeologist and former director of the Missouri State Museum.

He credits the judge and Ed Buel with his decision to enter the field of archeology. He added, "Judge Dalton was genuinely nice, and the most ethical and principled man I ever knew."

Dalton's son, Andy, recalled Supreme Court judges did not wear robes in those days. But when there was a move to do so, his father resisted because "he felt like that set them apart from the common people."

He was a very humble man. Would we all be so humble if a prehistoric culture was named after us?

Jenny Smith is a retired forensic chemist at the Highway Patrol Crime laboratory and former editor of Historic City of Jefferson's Yesterday and Today Newsletter.