Roger Hager has long been a person of reflection, piecing together cross-sections of family and local history in an effort to acquire a better understanding of how military service shaped the lives of his ancestors.

Most recently, he has collected information regarding the World War I service of his late great uncle, who was among the brave Marines who earned the admired title of "Devil Dogs" in the historic Battle of Belleau Wood.

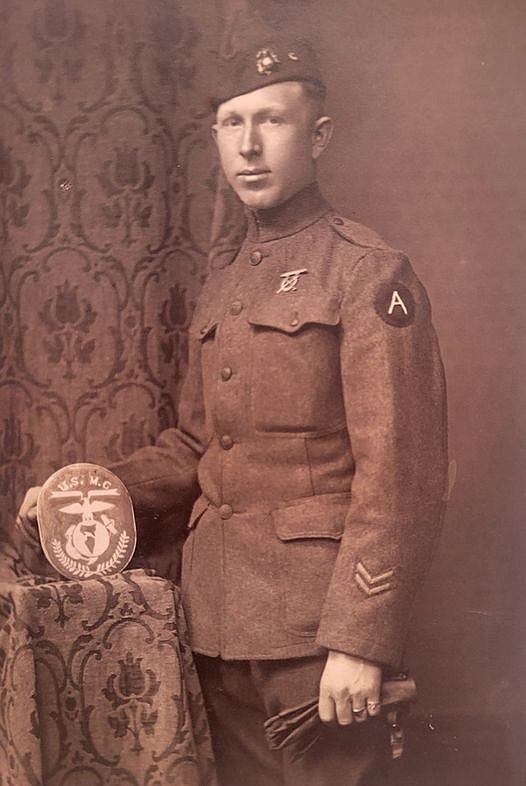

Willard Paul Gress was born in St. Thomas on Nov. 24, 1890. The 26-year-old was single and employed as a grocery clerk with L.O. Harris in Kansas City when he joined tens of thousands of young men from across the United States registering for the military draft on June 5, 1917.

"He chose to enlist in the United States Marine Corps in Kansas City on December 15, 1917," said Hager, when discussing his long-deceased great uncle. "It's interesting that he had to be re-examined because, at first, he was considered to be underweight -- a tall man who was only 143 pounds," he added.

Military records indicate the recruit was initially sent to Parris Island, South Carolina, to embark upon his training. While in camp, he received instruction in a variety of military skillsets that would be critical to his survival in the coming months.

"The course of instruction at Parris Island lasted eight weeks," noted a Marine Corps Recruit Depot History Book accessible through the U.S. Marine Corps website. "The first three weeks were devoted to instruction and practice of close order drill, physical exercise, swimming, bayonet fighting, personal combat, wall scaling and rope climbing."

During the fourth and fifth weeks of their World War I training cycle, the book said, recruits "perfected their drills, learned boxing and wrestling, and were taught interior guard duties," with the final three weeks being dedicated to refining their marksmanship skills.

Like many service members of the era, Gress took out a $10,000 insurance policy on Feb. 11, 1918, accepting the possibility that should his return to the states be inside a flag-draped coffin, his family would have the means to provide for his burial with funds remaining.

When his initial training completed on Feb 23, 1918, the new Marine was assigned to the 138th Company, 2nd Replacement Battalion in Quantico, Virginia. The following month, he boarded a troop ship bound for overseas service.

"There are records showing he was eventually assigned to the 78th Company, 2nd Battalion of the 6th Marine Regiment and embarked for overseas duty on March 14, 1918 at (League Island) Philadelphia," Hager said. "After arriving in France, they began a period of intense training," he added.

The Marine's mettle was soon tested in operations against enemy forces. As Gress explained in later years, the fighting was not the greatest challenge he endured in the war, since on many occasions he recalled going for three or four days without anything available for them to eat.

"The (78th Company, 2nd Battalion, 6th Marines) fought at the Battle of Belleau Wood for which they were awarded the Croix de Guerre with Palm from the French government," explained an article by the Great War Association. "Beginning October 3, 1918, the 6th Regiment led the offensive to take Blanc Mont Ridge, pushing the Germans out of the Champagne Region of France."

An article by the 2nd Marine Division cites the Battle of Belleau Wood as the basis for the Marine Corps' esteemed nickname of "Devil Dogs." The story reveals Marines were ordered to take a hill under control of entrenched German forces, while at the same time wearing gas masks to protect against the dangers of mustard gas.

"While the Marines fought their way up the hill, the heat caused them to sweat profusely, foam at the mouth and turned their eyes bloodshot, and at some points, the hill was so steep it caused the Marines to climb up it on all fours," the article vividly explained.

"From the Germans' vantage point, they witnessed a pack of tenacious, growling figures wearing gas masks, with bloodshot eyes and mouth foam seeping from the sides, advancing up the hill, sometimes on all fours, killing everything in their way. As the legend goes, the German soldiers, upon seeing this spectacle, began to yell that they were being attacked by 'dogs from hell.'"

Gress and his fellow "Devil Dogs" of 2nd Battalion fought in many historic battles of World War I, concluding with the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. When the war came to an end with the armistice on Nov. 11, 1918, he remained in Germany as part of the occupying forces until returning to the U.S. in June 1919, receiving his discharge shortly thereafter.

After the war, he worked as a farmer, married and raised two daughters and two sons. In 1950, Gress moved to Warrensburg, where he remained the rest of his days, employed as a farmer and carpenter. The 89-year-old veteran died in 1979 and lies at rest in Warrensburg Memorial Gardens Cemetery.

Hager never had the opportunity to become closely acquainted with his great-uncle prior to his death decades ago, but has enjoyed learning more about a man who stalwartly defended his country in WWI and proudly carried the "Devil Dog" title.

"His dog tags and some of the beautiful trench art he crafted, like an engraved mess kit, are displayed in the Johnson County Historical Society," Hager said.

"Just to demonstrate the type of person he was, while listening to the radio in World War II, the government was asking former servicemembers to consider joining to serve in non-combat positions. He wrote them to say that he wanted to come back and serve in the Marines, but they didn't accept him."

Grinning, Hager added, "That's true dedication to the Devil Dog spirit."

Jeremy P. Ämick writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.