Just east of Jefferson City and north of Osage City is a delightful historic site of about 14 acres, Clark’s Hill/Norton State Historic Site.

In the early 1800s, the bluff overlooked the confluence of two major rivers, the Missouri and the Osage. In 1804, this bluff also was the site for the intersection of two major cultures: Capts. Meriwether Lewis and William Clark with the Corps of Discovery and the Osage tribe.

Donated to the state by William and Carol Norton and family, and managed by the Department of Natural Resources, Division of State Parks, the site is called “Clark’s Hill” because Capt. Clark climbed the bluff while the expedition camped below. It was also Carol Norton’s wish to honor the native culture at the site.

Near Clark’s Hill, an Osage village once existed on the Missouri River. After his ascent to the bluff, Capt. Clark recorded seeing two burial mounds from the Late Woodland Period (500-900 AD).

As Nov. 26 was Native American Heritage Day, this account will focus on the Osages, who were dominant in Missouri at the time and who claimed a large area of land south of the Missouri River including Cole County and Clark’s Hill.

Historically, the Osages were part of a Siouan language subgroup, the Dhegiha, and were first known to live in the Ohio River Valley. These groups began to move west and south, later merging at Cahokia Mounds. In a court case concerning Sugarloaf Mound in St. Louis, the Osage Nation established that the present-day Osage people are descendants of the Mississippian culture at the mounds.

The tribe had long been active in Missouri, especially for winter hunting and trapping trips. In fact, the Osages were here from about 500 A.D. to the beginning of their land cessions in 1808.

About the time of the Marquette and Joliet visit in 1673, they were beginning to move further into the Ozark area south of the Missouri River. This move probably was their most concentrated occupation near Clark’s Hill.

“Throughout Osage ancestral homelands, there are a variety of Osage sites. … This includes Osage villages, hunting camps, camps, trails, sacred sites, rock art and several types of Osage burial sites,” said Dr. Andrea A. Hunter, tribal historic preservation officer. As a people whose name “Wah-Zha-Zhe” means “The Water People,” the Osage were “close to water and the strength of it.”

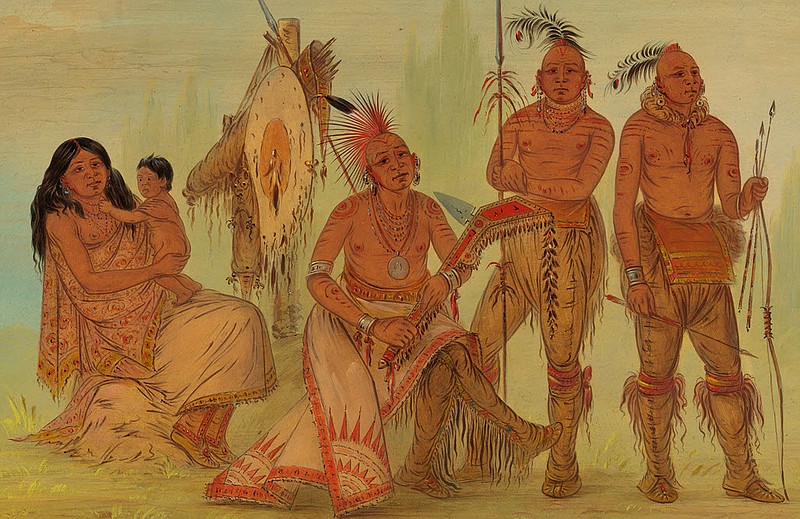

They were a very spiritual people with strong family ties, excellent hunters and farmers. Tall, proud and often at war with other tribes, their warriors were fierce in protecting their material goods and people, seeing battle as the most honorable way to die. Mike Dickey, Arrow Rock State Historic Site administrator, referred to the Osage and Spain as “two imperial powers,” putting the Osage on par with Spain as a force to be reckoned with.

For 40 years prior to the Louisiana Purchase, the Osages were the pre-eminent traders in Missouri, mostly in furs, but also horses, bison and native people captured further west.

However, while the Corps of Discovery saw signs of native war parties and pictographs when traveling through Missouri, they did not encounter any Osages. By this time, their villages were located further up the Osage River in the prairies. Furthermore, tribal members were hunting bison further west.

For native tribes, the change from European ownership did not seem significant at the time. Tribes had benefited from long-established trading patterns with the French, Spanish, British and Americans that they expected to continue. We now know the change was significant and led to a loss of tribal land and culture.

Missouri no longer has any federally recognized tribes. In the early 1800s, the federal government began a series of actions to relocate the Osage. By 1825, treaties were signed that forced them to give up their land at about one cent per six acres. In 1865, the government again moved them to Oklahoma.

The tribe has since worked diligently to regain its history and tribal sovereignty — a process helped by wealth from a discovery of oil and natural gas underneath their lands.

In 2004, the Osages celebrated attainment of Sovereign Nation status and ratified a constitution in 2006. Pawhuska, Oklahoma, is the tribal capital, where the tribe was the first in the nation to establish its own museum.

Back at Clark’s Hill/Norton SHS, the mouth of the Osage River gradually moved further downstream toward Bonnot’s Mill. The Corps of Engineers moved the channel of the Missouri River to the north to benefit commercial navigation and flood control.

So, today, the two great rivers no longer meet at Clark’s Hill and the Osage is rarely seen. However, in winter after the leaves have fallen, both rivers can be seen, the Missouri on the northwest side of the point and the Osage to the east. The view is still a “delightful prospect,” in Clark’s words, and the site retains a quiet sense of the peoples who once roamed it.

Linda Vogt gives interpretive talks about the history of the Clark’s Hill/Norton SHS site and leads a volunteer group removing invasive plant species along the trail. November is Native American History Month.