[<a href="https://www.newstribune.com/news/health/" style="color:#33AEFF">access the News Tribune Health section</a>]

Editor's note: This is the first column in a two-part series about the Spanish Influenza. The second will be published next Saturday, April 5.

We are stalked by a dark shadow that threatens to envelop us with the scariest health challenge in more than a century. We are taking the coronavirus seriously because our ancestors throughout the world were devastated by a virus misnamed "Spanish Influenza," and its terrible impact has remained a specter within our culture.

The worldwide death total was at least 50 million people, maybe 100 million. In this country, 670,000 deaths were attributed to it, more than the combined death counts in both world wars, Korea and Vietnam. Missouri's total was 12,250. To put that in context, the population of Jefferson City was a little less than 14,500.

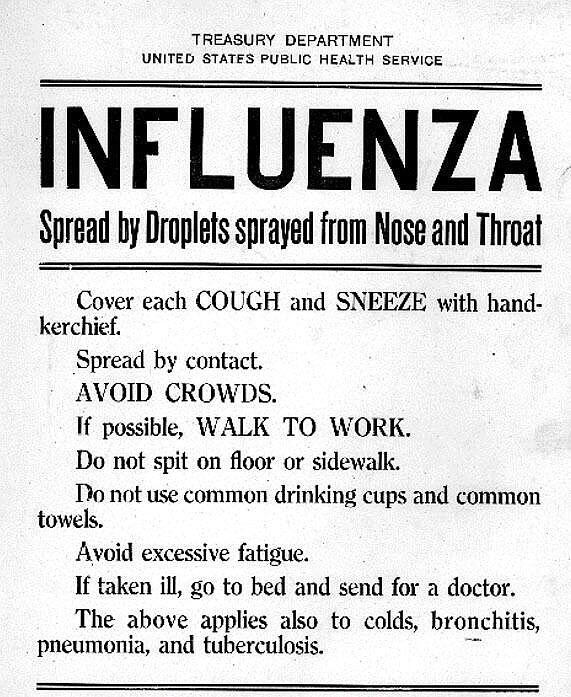

Missouri had no cases of Spanish Influenza when St. Louis Health Commissioner Max Starkloff issued three "don'ts" to fight the spread of the disease "if it reaches here."

Don't cough or sneeze unless your mouth is protected by a handkerchief. Don't, if you can avoid it, sleep in the same room with another person if you have influenza. Don't fail to call a doctor when the first symptoms are felt.

Less than three weeks later, on Oct. 8, the Jefferson City Daily Capital News reported the city's first apparent case - the secretary of the State Council of Defense, Frank Robinson.

"Local physicians are not alarmed over the prospect in any way, but they are ready to take all precautions necessary," the paper read.

Two days later, the schools closed; churches cancelled services indefinitely; students at Lincoln Institute were forbidden to leave the campus; gatherings of more than 15 people were prohibited, and streets were ordered flushed each morning.

"These precautions are deemed sufficient to prevent the spread of the influenza epidemic in the city," the newspaper read.

The next day, the city had "no fewer than 50 cases." By Oct. 15, there were 65, and former Madison Hotel clerk Raymond Smith had become the city's first fatality. Among the newly infected people was city physician Dr. Edward Mansur, with a "mild form."

The city counted 150 cases Oct. 17, and, a day later, the number topped 185. The city already had a serious shortage of nurses, and by Oct. 22, community Nurse Ruth Porter was in bed with the flu, too.

Churches were allowed to have services for the first time in two weeks, but the theaters and schools remained closed.

Forty-two new cases were recorded Oct. 23-26. The number of cases passed 300 by the end of October. About a dozen people had died by Nov. 14.

The newspaper published a large public notice on the front page citing "unusual measures" were being taken to "remove the influenza from our city." Some of them sound familiar today. Others speak of the sanitation issues of the day:

Spend a lot of time out of doors but away from crowds.

Open doors and windows of your homes, especially in the bedrooms, for a few hours each day and clean out dirty corners.

If anyone in your home has had a cold or even felt bad fumigate their bedrooms - if not the entire house. Fumigation can be done by anyone - with sulphur or formaldehyde candles.

It is the duty as well as a law that every contagious disease be reported to the city physician for the protection of yourself as well as your neighbor.

Business houses are urged to at least fumigate their stores one night this week. Those businesses serving other than alcoholic beverages must wash glasses and china used by patrons in hot water and with soap. Saloons must wash glasses used by patrons more thoroughly than usual. Water basins used for the washing must be emptied and refilled at least four times a day. And care must be exercised to keep large numbers of people from gathering in those businesses. Even small groups must be made to spread out. Any business allowing more than 15 people to assemble or enter the place at one time could be closed.

All business places must have prominent signs asking people not to cough or sneeze in their places. Such signs will cause people to cough or sneeze into their handkerchief.

Factory superintendents must take the temperature of all employees at least once a day and anyone who is 99 or more must be sent home and not allowed to return until he has a doctor's certification that he is not affected with a contagious disease. Each factory must be fumigated at least once a week.

The city board of health agreed a couple of days later to delay any closings for four days. If, on Nov. 22, "there is not a decreased number of influenza cases reported daily in the city, the businesses houses will be closing tight for four days in an effort to stamp out the disease."

The Miller and Weiss Pool Hall on Madison Street was closed for a week after a policeman found 31 people inside.

We'll have more next week.

Bob Priddy is a journalist and historian who has authored five books on Missouri history. He has reported on legislative issues over the years and more recently in his blog at bobpriddy.net. He served as news director of The Missourinet from its beginning in 1975 until his retirement in December 2014 and was the immediate past president of the State Historical Society of Missouri.