Silence is a fickle thing. Sometimes it haunts people like Jerry Koenig and other survivors of life-altering atrocities, but sometimes it's also an invitation to share memories of those horrors to educate and hopefully transform lives.

Koenig is a Holocaust survivor, a Polish Jew who made it through the slaughter with his mother, father and younger brother. He later settled in the United States.

He shared his story of survival and the life he's led since to Helias High School sophomores Friday, alongside his wife, Linda.

Student Maya Heckart said she "thought it was a great privilege" and "a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity many people don't get" to hear a survivor's story.

The unique opportunity for students was something English teacher Sarah Kempker affirmed, too.

Helias sophomores began reading "Night" in classes four years ago, Kempker said. "Night" is the memoir of the late Romanian-born Jewish writer, philanthropist and Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel, who chronicled his experiences at the infamous Nazi death camp Auschwitz-Birkenau.

For the first two years of teaching the book, Kempker said another survivor was brought in to speak. At the time, he was the youngest survivor alive in the United States, but he passed away last spring.

For the past two years, they've invited Koenig - having found him through his connections to the Holocaust Museum and Learning Center in St. Louis.

"We hope to provide this opportunity as long as we can," she said.

"It authenticates what they read," fellow English teacher Kathy Jarman said.

"Actually hearing the words come from someone's mouth who lived it (is a reminder that) history is real," said Jeff Pickering, who teaches politics and world history at Helias. "It's easy to forget these were real people."

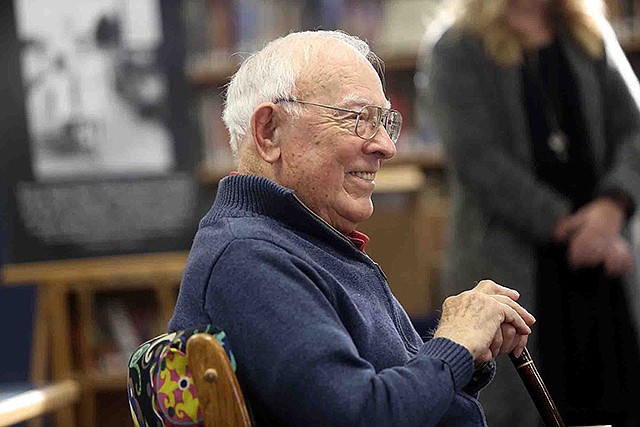

When Nazi Germany invaded Poland in 1939 and ignited all-out war in Europe, Koenig was 9 years old. On Friday, he sat in front of about 100 students as an 87-year-old man who walks with a cane and whose hearing isn't what it used to be.

Because he wasn't feeling his best, Koenig answered students' questions but first sat with them and watched a recorded presentation of his story he gave about six years ago, rather than telling it in person.

Silence descended en masse over the audience of students as Koenig approached his seat.

Even though he has had 78 years of historical and geographic separation from those events, the memories of the time when he, his family, friends and neighbors were hunted, penned in and forced to hide - often pursued by other neighbors - are still raw.

"For the longest time, I didn't speak to groups," he said in the recorded presentation. He said it doesn't get easier the more times he tells his story.

Home for Koenig in 1939 was a suburb 8 miles outside Warsaw, the capital of Poland. Koening and his family were among the large Jewish minority population of approximately 3 million in Poland.

His middle-income family owned a 60-acre farm - large by Polish standards -about 100 miles from Warsaw.

After the Nazis occupied the country, Koenig said, the treatment of Jews "was demeaning, maybe not necessarily life-threatening."

Jews had to identify themselves by wearing white armbands with blue stars and had to give right-of-way - and bow - to Nazi military men on the street.

He said the entire country's food supply was rationed, but Jews got smaller rations than people of the Catholic Slav majority.

Then came the ghettos.

Jews, including Koenig's family, were rounded up and forced into dilapidated neighborhoods that quickly became overcrowded and lacked basic sanitation.

A few potatoes, carrots or maybe a loaf of bread could be bought on the black market for exorbitant amounts of money most people could not afford.

He still feels some guilt from that time. Other young, agile boys would leap over the walls that surrounded the ghetto and buy, beg or steal food to smuggle back in.

Koenig didn't do that. His parents never asked him to, probably because the penalty for being caught was to be shot on sight.

It became clear to the family life in the ghetto would remain untenable - even before people began to be shipped off to the Nazi death camps, including the nearby Treblinka.

Koenig explained there were thousands of concentration camps across Europe at that time.

People died there in droves from brutality and deprivation, but the death camps were another breed. They were designed to be efficient centers of mass murder.

"What hurts the most," he said, is the German people allowed themselves to be convinced by the Nazis "it was perfectly all right to murder people."

In the ghetto, his family got in touch with a human smuggler who operated on the trolley line that ran in and out of the ghetto.

Normally, Christians were forced to get off the trolley at the ghetto's entrance, and Jews who had been permitted to leave had to get off in the ghetto before the trolley crossed back into non-guarded areas. The smugglers bribed all the right people, though, and Koenig's family was able to cross.

Most of their family who stayed behind were eventually sent to Treblinka and murdered.

The town Koenig's family made it to was relatively unbothered by the Nazis, but that was because the Jewish townspeople there served as a labor supply force for Treblinka.

"It became pretty obvious that that was not going to last forever," he said.

His father offered their family's farm as a bargaining chip to two Jewish brothers in town - ages 18 and 22, who had already lost their parents - in exchange for finding a non-Jewish family who would hide them.

That family built a bunker under their barn, which barely fit what would ultimately be the 11 people who hid in the hole in the ground, only big enough to allow one person to stand up at a time.

Koenig's family was in that hole for 22 months with limited food and no way to wash. Bed bugs and lice were everywhere.

Some time later, Soviet troops advanced into the area, and the 11 survivors were able to emerge from their hiding place.

After continued violence through the following year, the family decided there was no future for them in Poland. They immigrated to the U.S. in 1951, settling in Iowa initially but later coming to St. Louis following family connections.

When a student asked Koenig if he was still a practicing Jew, he joked initially that he doesn't have too much of a choice in some regard, given Judaism's custom of circumcising newborn boys - which wasn't the medical norm at the time.

In terms of spirituality, though, Koenig was blunt in saying he is no longer a practicing Jew.

Some Holocaust survivors thank a higher power and their faith for their survival. Koenig and others blame the almighty, though, or at least wonder why he was "asleep at the wheel."

"I can't help it," he said, adding "why" is too difficult of a question to avoid. He cited German soldiers who wore a belt that translated as "God is with us" even as they brutally murdered innocent people.

He said sometimes, even on otherwise bright and sunny days, dark thoughts still pop back unexpectedly into his head. Fortunately, that doesn't happen too often.

"You're not very anxious to re-hash these things," he told the students.

However, after sharing his story with his wife as they were getting to know each other, she encouraged him to share it with wider audiences.

"Like any other good husband, I listened."