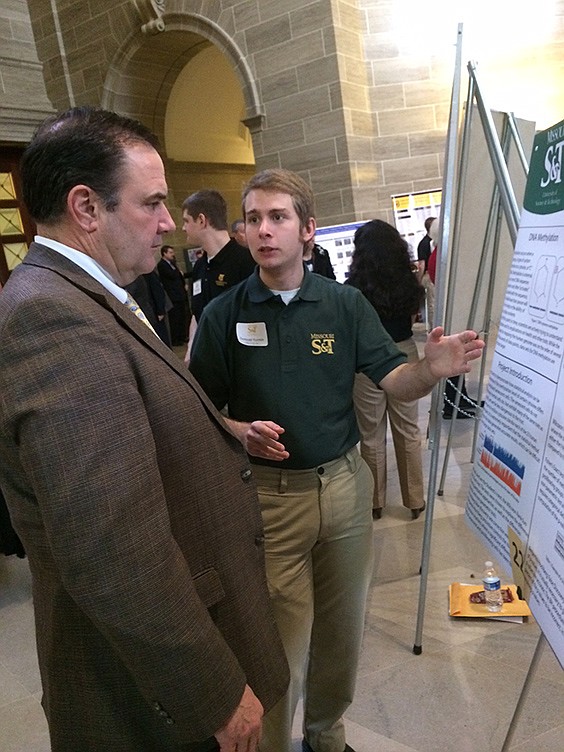

Jefferson City High School graduate Samuel Turpin, 22, was back at the Capitol on Tuesday. He wasn't talking about politics or legislation or appropriations, and he wasn't on one of the annual field trips he took in elementary, middle and high schools.

Instead, Turpin was talking about DNA methylation and biostatistics.

A Missouri University of Science and Technology senior, Turpin was one of 46 undergraduate students from the four UM System campuses sharing their research with lawmakers, staffers and visitors beneath the Capitol Rotunda.

Turpin's research with Dr. Gayla Olbricht was a statistical analysis of DNA markers to find sites within DNA strands where there is a high likelihood that certain diseases can be predicted.

At Missouri S&T in Rolla, students are encouraged to take part in research with faculty, identifying the niche that most reflects their interests and research goals.

"I'm interested in partial differential equations. Do you have any partial differential equations I can work on?" he said of the process students undertake to find the projects they are interested in.

Turpin knew he wanted to use statistics to analyze particular biological functions, and Olbricht's research fit the bill.

Turpin and Olbricht studied a rare type of cells called senescent cells that don't divide or die and keep growing and consuming nutrients. They were trying to find where on DNA the presence of these cells could be predicted. They looked at methylation sites were a type of carbon chain attaches to the cytosine bases of DNA.

Turpin used data available online from the National Institutes of Health that showed the differences in methylation between senescent and normal cells in different patients. If at a specific cytosine base, there was a large difference in how the methylation was occurring between the senescent and normal cells, that site could be considered predictive of whether or not senescent cells would be present in a particular patient.

The biggest challenge in Turpin's research was finding a computer powerful enough to analyze the enormous dataset he was using. He was only able to analyze the first 5,000 cytosine sites, which took his computer 10 minutes to crunch. The first 2,000 sites took just one minute, so as the dataset grew, the amount of time it took to analyze increased exponentially, he said.

"I tried to run two million sites over three days (on Rolla's supercomputer), and it didn't even finish collecting the data," Turpin said.

While presenting his research, someone from the University of Missouri - Columbia told Turpin he should try to access the supercomputers at MU to complete his analysis.

While he found no statistically significant sites in the first 5,000 sites he examined, Turpin was confident if he were to analyze the full dataset of 100 million sites, he would surely find some that had significant differentials to count as useful in identifying whether someone was likely to have or not have the senescent cells.

"I spent a lot of nights up until one in the morning, figuring out the different errors (in the analysis)," he said. "But it was really rewarding to see it work."

The significant sites would indicate that these places on the DNA strand played an important part in activating or deactivating the senescent cells. Researchers or doctors could use those sites to predict people who were most likely to have senescent cells present and could then do further diagnostic testing to determine what people needed actual treatment.

Turpin said his method could be used to test any hereditary trait - from a high likelihood of cancer to someone's eye color.

"Any hereditary trait is associated with methylation, so if you have the computing power, you can use it as a diagnostic or predictive test," Turpin explained.

After graduation this May, Turpin will be heading to Lawrence to begin work on his master's degree in applied mathematics at the University of Kansas and hopes to eventually work toward a doctorate.

"I would really like to do research in academia or work in biostatistics for a company or hospital doing whatever is the cutting edge thing at the time," Turpin said.

Turpin's work impressed Sen. Mike Kehoe, R-Jefferson City, who was left imagining the countless applications as technology continued to improve over time.

"If I had 45 days, I might be able to understand what he has successfully done," Kehoe said after Turpin gave him a summation of his research. "It's incredible to think up what to research and how to do it and then to actually do it."

Kehoe was full of praise: "He's very impressive. I told Sam, I hope my kids are half as smart as he is."