SALT LAKE CITY (AP) — A microscopic thread of DNA evidence in a public genealogy database led California authorities to declare this spring they caught the Golden State Killer, the rapist and murderer who had eluded authorities for decades.

Emboldened by that breakthrough, a number of private investigators are spearheading a call for amateur genealogists to help solve other cold cases by contributing their own genetic information to the same public database. They say a larger array of genetic information would widen the pool to find criminals who have eluded capture.

The idea is to get people to transfer profiles compiled by commercial genealogy sites such as Ancestry.com and 23andMe onto the smaller, public open-source database created in 2010, called GEDmatch. The commercial sites require authorities to obtain search warrants for the information; the public site does not.

But the push is running up against privacy concerns.

“When these things start getting used by law enforcement, it’s very important that we ensure that to get all of the benefit of that technology we don’t end up giving up our rights,” said American Civil Liberties Union legal fellow Vera Eidelman.

She argues when someone uploads their own DNA profile they aren’t just adding themselves — they’re adding everyone in their family, including dead relatives and those who haven’t been born yet. She also said DNA mining could lead to someone’s predisposition to mental and health issues being revealed.

“That one click between Ancestry and 23andMe and GEDmatch is actually a huge step in terms of who has access to your information,” Eidelman said.

This month, DNA testing service MyHeritage announced a security breach revealed details about more than 92 million accounts. The information did not include genetic data but nonetheless reinforced anxieties.

Nevertheless, the effort is gaining steam with some genetic genealogy experts and investigators.

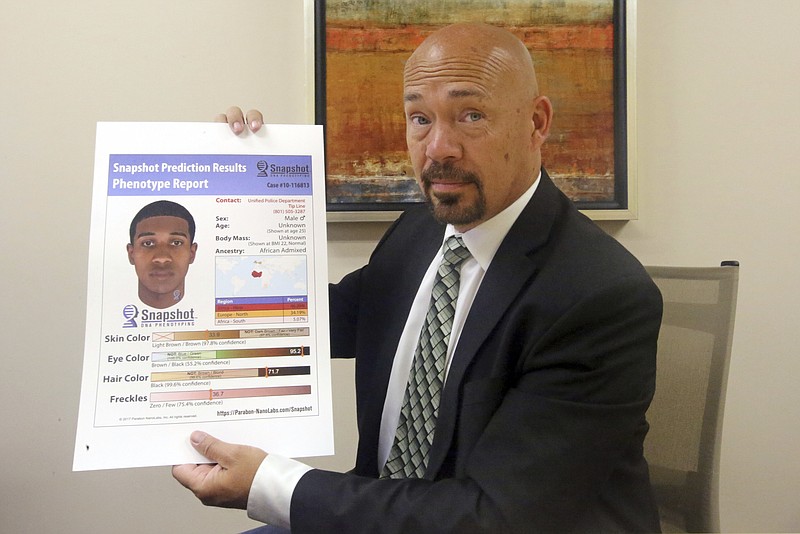

The shared DNA profiles “could end up being the key to solving one of these cold cases and getting the family closure and getting someone really dangerous off the streets,” said CeCe Moore, the head of the genetic genealogy unit at the DNA company Parabon NanoLabs.

She’s uploaded her personal genetic information to the public database and wants it to become a larger repository of information for genealogy hobbyists and investigators alike. Separately, Parabon NanoLabs has also uploaded DNA data from 100 unsolved crime scenes in hopes of finding suspects.

Genetic genealogy has traditionally been used to map family histories. Labs analyze hundreds of thousands of genetic markers in an individual’s DNA, compare them with others and link up families based on similarities. The public database was created to compare family trees and genetic profiles between the commercial sites, which don’t cross-reference information.