Missouri's share of funding for the state's Medicaid program has been on an upward trajectory.

When Gov. Mike Parson selected former House Speaker Todd Richardson to direct MO HealthNet, the state Medicaid program, late last year, the governor tasked Richardson with containing the rising costs of Medicaid, improving the program's sustainability, and examining rural health care and hospital closures.

In 2009, Missouri Medicaid spending was equal to 17 percent of the state's general revenue. By 2018, it was 24 percent.

If unchecked, the growth in spending is expected to reach 26 percent by 2023, according to Richardson.

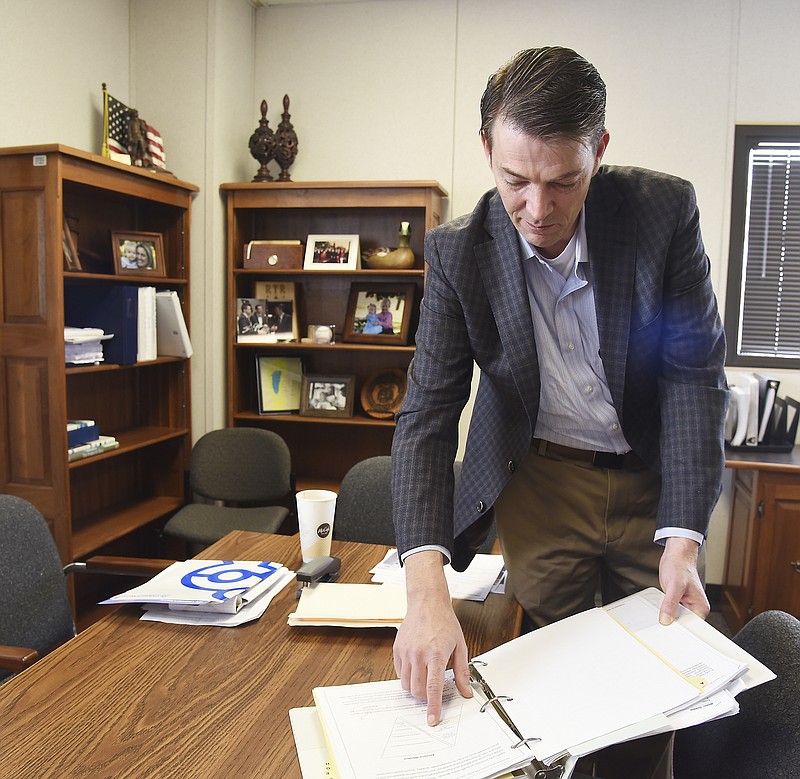

He discovered a stark reminder of the job he had undertaken when he walked into his new office Nov. 1.

"When I came out here to the office and walked into the director's office, there was a desk and a telephone," Richardson said. "Over on the bookshelf, there was a 3-inch, three-ring binder that had '2006 Medicaid Transformation' on the spine. It's still there today."

The binder hints at a job that has vexed lawmakers for decades, since Congress passed legislation in 1965 creating the programs to provide health care for the country's aging and vulnerable populations.

President Lyndon Johnson signed the programs into law in Independence, hometown of President Harry Truman, who was present and became the first Medicare enrollee, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

The programs have grown and changed over the years. Within two years of it being signed into law and facing financial challenges, Congress limited - by income - who could enroll. In 1972, expansion of Social Security added to the eligibility rolls. A proposal from President Ronald Reagan's administration attempted to convert Medicaid to block grants but failed. Medicaid was expanded to cover poor children in 1997.

About $593 billion was spent nationally on Medicaid in 2016, according to medicaid.gov. The program cost $10.3 billion in Missouri in 2018.

The state's administration and lawmakers are looking at how they might contain growth in Medicaid spending and bring it in line with the state's growth in revenue.

Growth in spending

Then-Gov. Matt Blunt's administration developed the 2006 transformation plan for Missouri a year after his office slashed about 175,000 Missourians from Medicaid's ledgers.

Among other things, the plan rebranded the state's program, calling it MO HealthNet. Blunt called for an emphasis on preventive health care and rewards for people who try to stay healthy and more pay for patients who treat healthier patients, according to the Associated Press.

Health care coverage was to be expanded to some children, and small businesses were to be able to receive state aid if they provided insurance to lower- to middle-income employees.

Missouri implemented a few of the recommendations in the 2006 report, but the state fell short of an overall transformation of the program.

But because the state is late to the game in transforming its Medicaid program, it has the benefit of seeing what has worked well for other states and what has not, Richardson said.

State leaders have three "pillars" for the transformation, he said:

- To build a best-in-class Medicaid program other states would see as a model.

- To meet the needs of Missouri's most vulnerable residents.

- To do it in a way that's financially sustainable.

The cost to Missouri for the Medicaid program is outpacing growth in state revenue, he said.

When Richardson arrived as a freshman state lawmaker in 2011, Medicaid spending was 17 percent of general revenue. Now, it's at 24 percent.

Revenue has also grown during that period, but not as fast as spending.

"That's a significant amount of growth in eight years," he said. "We know from that historical trend-line, if nothing else changes in the program - and nothing bad happens - that number will be 26-plus percent by 2023.

The Rapid Response Review, a study of the state's Medicaid system completed in February, says the spending could increase to as much as 30 percent by 2023.

"If you look at other determining factors - if there's a downturn in the economy, which will have a drop in general revenue and a spike in enrollment - that number's going to grow," he said.

Thirty percent is probably a worst-case scenario, he added, but could lead to the Legislature having to come up with $600 million from general revenue just to balance the state budget to maintain the program.

"The reason that that is important is, if you don't address some of that cost growth in the program before we get there, the tools that will be at our disposal to deal with it are really painful," Richardson said. "They are things like having to cut provider rates. They are things like the Legislature having to look at eligibility or looking at cuts in other programs that are priorities for the state to fund."

What is Medicaid?

A $10 billion-plus program in Missouri, Medicaid provides medical coverage for eligible low-income adults, children, pregnant women, elderly adults and people with disabilities.

States and the federal government jointly fund the program, which the states administer according to federal requirements.

Three Missouri agencies oversee different parts of the Medicaid program - the departments of Health and Senior Services, Social Services and Mental Health.

Social Services operates the MO HealthNet Division, which is responsible for medical expenses for eligible participants and represented $7.9 billion in spending for 2018.

Mental Health administers services for participants with developmental disabilities or learning disabilities and community-based health centers, psychiatric rehabilitation substance treatment and home health programs and represented $1.5 billion in spending.

Health and Senior Services administers benefits for adults 18 and over and clients younger than 21 with special health care needs and represented $.9 billion in spending.

MO HealthNet provides health care and support for more than 900,000 people.

Children in low-income families make up about 63.5 percent of participants, pregnant women and custodial parents make up 12.3 percent, and seniors and people with disabilities make up about 24.2 percent, according to the Rapid Response Review - Assessment of Missouri Medicaid Program.

The review was conducted by McKinsey & Co., the former employer of Missouri Chief Operating Officer Drew Erdmann.

What is the review?

The review examined the entire Medicaid program, including health outcomes, participant experiences, operational efficiencies and cost of management.

It resulted in the company identifying several dozen "opportunities" for changes within the program that could help it improve sustainability and reduce the rate at which Medicaid grows in the state. The report includes descriptions of the opportunities (with supporting data) and potential initiatives that "may be considered by the state in shaping its approach to Medicaid."

According to that report, although seniors and people with disabilities make up only 24.2 percent of Medicaid enrollees in the state, they are responsible for 62.9 percent of the program's expenditures.

All elderly and 40 percent of people with disabilities are dually eligible for both Medicaid and Medicare. For people with this dual eligibility, Medicare pays for acute care costs that include hospitals, physicians' fees and medications, while Medicaid pays for long-term care and support (nursing homes and home health care).

How much does MO HealthNet cost?

For fiscal year 2018, the Missouri Medicaid (MO HealthNet) program cost $10.3 billion; $2.2 billion came from the state's general revenue fund, $5.5 billion from federal funds and the other $2.6 billion from other funds, consisting primarily of revenue from provider taxes ($1.4 billion), which came from hospitals, nursing homes, pharmacies, and ambulance and emergency medical services.

Missouri hospitals pay in about 5.95 percent of net patient hospital revenue (what hospitals are paid for patient care services), just under the federally allowable maximum of 6 percent, to allow for "wiggle room," according to Daniel Landon, vice president of governmental relations for the Missouri Hospital Association.

These provider taxes, called Federal Reimbursement Allowance, are used to attract federal matching funds.

The matches vary state-to-state, depending on how "well to do" the state is, Landon said. Mississippi, for example, has a match rate of 77 percent, which means for every $23 the state contributes, the federal government matches it with $77. The minimum match is 50/50. California, Washington, New York, Colorado and several other states' matches are that low.

Missouri's rate is 65/35.

"In Missouri, if you put up 35 cents of state money, which can include the provider tax, you receive 65 cents of federal money," Landon said.

Brian Kinkade, the hospital association's vice president of children's health care and medical policy, said Medicaid doesn't recognize all the costs that go into providing care for enrollees. It pays for about two-thirds of costs.

That annually leaves Missouri's hospitals facing shortfalls. For fiscal year 2018, association data show there were about $647 million in unpaid Medicaid and $740 million in unpaid Medicare costs wracked up in Missouri's hospitals. Many losses are overcome through higher rates charged to commercial insurance providers, Kinkade said.

"All those dollars have to come from some place," he added. "Some hospitals operate in the red. Some operate in the black. You can only operate in the red for so long."

The Missouri Emergency Medical Services Agent Corporation, a nonprofit organization, collects user taxes from ambulance and emergency medical services and in turn distributes MO HealthNet reimbursements to participants. The user payments peaked a couple of years ago at about $15 million per year, according to Jason White, a board member for MoEMSAC.

They have gone down to about $14 million recently, White said, some of which comes back to emergency health providers.

But not enough to cover their costs.

"The heart attack patient is going to - if they're on Medicaid - the ambulance service may get $300 for taking care of a Medicaid patient," White said. "It may actually cost $700 (to treat and transport the patient). There's a $400 difference. Who covers it? Well, in Cole County, you do."

The organization's tax is based on participants' gross receipts. For providers operated by local governments like Cole County Emergency Medical Services, White said, an Intergovernmental Transfer Agreement that went into effect in 2018 allows the provider to recoup more revenue. Through the agreement, providers may obtain a state match, he said.

"That program is being used by 50 services in the state," White said.

Richardson has been working with stakeholders and lawmakers to begin a process for stabilizing the state's Medicaid program financially.

"I think it's important that we recognize and are serious about the need to bend that cost curve and to bring that growth in line with growth in the rest of the state's economy," he said. "That doesn't mean we're going to find a way to magically make Medicaid spending drop overnight.

"It means: How can we do a better job administering the program and improve health outcomes that will help bend that cost curve?" he said.

Health care is unique, he said, in that the better job someone does in improving outcomes, the lower their costs will be.

"So that's got to be our primary focus," Richardson said.

The Rapid Response Review points out that the state paid $4.2 billion in fiscal year 2018 on acute care services - including hospital, clinic, physician and diagnostic services. Payments for those services were almost exclusively compensated on a fee-for-services basis.

"A significant proportion of Missouri Medicaid acute care expenditures is associated with potentially avoidable exacerbations and complications and inefficiencies in the choice of provider, site or treatment," the report states. "Potential initiatives to improve incentives and reduce costs include adjusting rate-setting methodologies, moving to value-based payment models, and investing in the rural and safety net health care infrastructure, including primary care and behavioral health."

The report found 75 percent of the state's Medicaid participants are covered by managed care - in which patients visit only certain physicians and their cost of treatment is managed by a company. Use of managed care may reduce costs for the short-term, it said, but it would not necessarily provide incentives to improve health outcomes.

That approach, coupled with value-based care - which shifts health care delivery from a focus on volume to one focused on outcomes - could save the state money in the long-term. The report listed off more than two dozen opportunities, which the state has for saving money in its Medicaid program.

Outcomes

No matter how the program is financed, it must produce better outcomes, Richardson said.

"I think we certainly have to move toward value-based care. I'm not sure that's mutually exclusive with managed care," he said. "Where we have to focus as a state, where we lag behind other payers and where we certainly lag behind some other states is in the use of value-based payment models."

The move toward value-based care has been a significant focus in health care, he said.

"I think it holds real promise for Missouri," Richardson added. "We sit at a unique place in that discussion, in that Missouri - by virtue of the fact that we haven't picked a path or a lane in that value-based payment discussion - we have the benefit of looking at what has worked in other states - and just as importantly, what hasn't worked."

Missouri has an opportunity to design a health system that gets it right, he said. Other states have "moved aggressively" toward models where better outcomes create better compensation for providers.

"That's the root of what I think we need to look at. The value-based component has got to be a big part of what we're doing moving forward," Richardson said.

Investment

The state has to invest in a better process to create better outcomes.

In Missouri, rates of hospital admissions are particularly high compared to the rest of the country, as are lengths of stays in hospitals, he said. Emergency department visits - and potentially avoidable visits - are high compared to the rest of the country. Re-admissions are high.

"It's all across the board. That suggests to me that we have to do a better job in investing in that primary care network - getting people the interventions they need on the front end, before (conditions) become complications that are far more expensive to deal with on the back end," Richardson said.

Investments in the primary care network are ultimately going to lead to program savings.

"Because if we're avoiding treating people in emergency departments - which is one of the most expensive places we can treat them - if we're avoiding hospital re-admissions, if we're reducing lengths of stays. All of those things lead to cost savings overall in the program," he said. "That's the challenge - to get it right and figure out how you make those investments.

"We're going to have to spend a lot of time thinking it through and thinking about it."

Within Parson's proposed budget for the 2020 fiscal year is a "new decision item" - a request for a new item in the budget - that would set aside about $500,000 to revamp hospital payment methodology and $35 million to begin the transformation effort, Landon said.

The proposed budget says the money would be used to begin efforts to modernize the program. The revenue will be used to change the payment reimbursement methodology, improve technology, look at some services and make certain the state has the proper analytical tools necessary for implementing the transformation.

Fortunately, the federal government offers 90/10 matches for most information technology projects or systems projects, Richardson said.

And the state's lawmakers are behind the transformation effort.

MO HealthNet has a lot of partners in the Capitol who are interested in seeing reforms to the program, Richardson said. They are unified in the mission to make it better but may not all agree on every component of the effort.

"Missouri is fortunate to have a strong universe of policy makers - both in the administration and in the Legislature - that have recognized Missouri Medicaid has got to change, and we've got to start that process now."

The process to transform Medicaid in Missouri has - in the past - started and stopped, as evidenced by the 2006 binder.

"The reason I left it there was to serve as a reminder to me - and I pointed it out to all of the team - that we don't want the '2019 Medicaid Transformation' binder to be sitting here collecting dust on a shelf at some point in the future. And the people who come after us to say, 'Why didn't they follow through on this? There were some good ideas in there. Why didn't it get done?'" Richardson said. "I'm going to be here as long as it takes to get the program in a better place than it is today."

He'll be focused on moving the program as quickly as it can to that "better place" because his team doesn't want the transformation effort to be something that stalls out.

It's too important, he said.

Not only for Medicaid.

Not only for the 900,000 Missouri participants it serves.

"But for every other area of state government," Richardson said. "The ability to invest in education. The ability to invest in infrastructure and our workforce - the governor's two primary priorities - are all impacted by how good a job we do at making this program sustainable."