Missouri does not explicitly require curriculum about the Holocaust to be taught in its schools. But it’s not clear if that will change after the recent mass shooting at a synagogue, or how teachers can adapt their lesson plans that incorporate Holocaust survivors’ testimonies as old age claims survivors and other eyewitnesses each year.

Anti-Semitism and how to combat it is on the minds of many people around the country after 11 mostly elderly people were shot to death Oct. 27 at a synagogue in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Authorities said the man who was arrested and charged after that mass shooting “expressed hatred of Jews during the rampage and later told police ‘I just want to kill Jews’ and ‘all these Jews need to die,’” the Associated Press reported.

More than 6 million Jewish people — along with millions of other people who were gypsies, disabled, Poles, Soviet prisoners of war, communists, Jehovah’s Witnesses and LGBT people, among others — were murdered across Europe by the Nazi German regime in the Holocaust.

Some states require public schools to have curriculum about the Holocaust — Illinois among them. States such as Connecticut and Rhode Island have enacted legislation along those lines in recent years.

In Missouri, the state’s Department of Elementary and Secondary Education has expectations of “content and skills which local districts are to use to frame their own curriculum,” but Missouri Learning Standards Expectations are not curriculum in themselves, DESE’s communications coordinator Nancy Bowles said. “Curriculum development and implementation are local school district responsibilities,” she said.

However, Bowles said, there are places in English and social studies MLS Expectations where school districts can place their “locally defined Holocaust and/or genocide studies.”

• Sixth-graders reading informational texts in English are expected to “explain how plot and conflict reflect historical and cultural context,” and similarly, eighth-graders are expected to “explain how the central ideas of texts reflect historical and/or cultural contexts.”

• In social studies, fourth-graders are expected to “research an appropriate social studies question and share the results with an audience,” and fifth-graders are to “identify, select, analyze, evaluate and use resources to create a product of social science inquiry with guidance and support as needed.”

• Middle school students in geography are expected to “analyze religion and belief systems of a place to determine their varying impact on people, groups and cultures.”

• High school world history students are expected to “explain connections between historical context and people’s perspectives at the time,” “evaluate the impact of nationalism on existing and emerging peoples and nations post-1450” and “analyze causes and patterns of human rights violations and genocide and suggest resolutions for current and future problems.”

DESE noted the Holocaust, as well as other 20th-century genocides in Cambodia, Rwanda and at Srebrenica, Bosnia-Herzegovina, are “mentioned specifically in the assessment and teacher support materials” for the expectation students study causes, patterns and resolutions of human rights violations and genocides.

“That may be a discussion we talk about with the commission,” Jean Cavender said of whether she might want to see a more specific Holocaust curriculum requirement in Missouri. Cavender is the chairwoman of the state’s Holocaust Education and Awareness Commission within DESE.

She’s also the director of the Jewish Federation of St. Louis’ Holocaust Museum and Learning Center.

“We haven’t pushed for it,” Cavender said of the commission and a curriculum requirement in the past, adding there is usually no funding available and “teachers just don’t like to be mandated in general about what they have to teach.”

She said of Illinois’ curriculum requirement “teachers can do as much as they want, or as little,” such as having students read a book or watch a movie — “it really just depends on the teacher.”

Illinois’ law requires “Every public elementary school and high school shall include in its curriculum a unit of instruction studying the events of the Nazi atrocities of 1933-45. This period in world history is known as the Holocaust, during which 6 million Jews and millions of non-Jews were exterminated. One of the universal lessons of the Holocaust is national, ethnic, racial or religious hatred can overtake any nation or society, leading to calamitous consequences.

“To reinforce that lesson, such curriculum shall include an additional unit of instruction studying other acts of genocide across the globe. This unit shall include, but not be limited to, the Armenian Genocide, the Famine-Genocide in Ukraine and more recent atrocities in Cambodia, Bosnia, Rwanda and Sudan. The studying of this material is a reaffirmation of the commitment of free peoples from all nations to never again permit the occurrence of another Holocaust and a recognition that crimes of genocide continue to be perpetrated across the globe as they have been in the past and to deter indifference to crimes against humanity and human suffering wherever they may occur.”

Cavender did not want to speculate as to what Missouri’s Holocaust education commission might discuss at its upcoming December meeting, but added “Who knows? (Last) Saturday changed everything. That mass murder (in Pittsburgh) really brought the evils of anti-Semitism to the fore.”

Cavender said the commission hopes to have a Holocaust commemoration next year, possibly at the Governor’s Mansion, or “perhaps doing some work around legislation or at least a proclamation around the evils of anti-Semitism and having some public visibility.”

Education about the Holocaust faces another issue, though — an aging population of survivors and other World War II-era eyewitnesses of crimes against humanity, such as U.S. soldiers who liberated Nazi concentration camps.

“Two of the three Holocaust survivors who have visited students at Helias have now passed away. Many students have been emotional when receiving the sad news. I do my best to explain to them that now they are the ones responsible for sharing the survivors’ stories. They are the ‘living history’ now,” Sarah Kempker emailed.

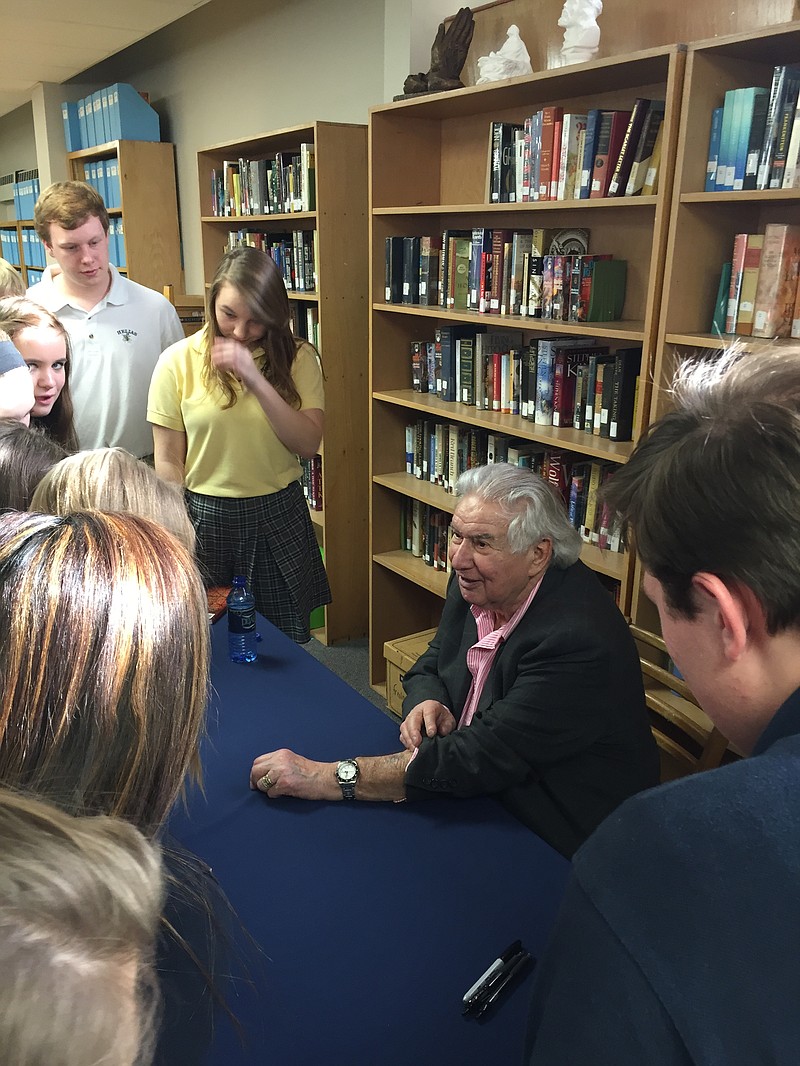

Kempker is an English teacher at Helias Catholic High School in Jefferson City and, for the past five years, has brought Holocaust survivors to speak to sophomores when they read Elie Wiesel’s “Night” — the late Romanian-born Jewish Wiesel’s memoir that chronicles his experiences at the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp.

“Many of my students, current and former, have told me that meeting a Holocaust survivor is and will remain one of the best and most memorable experiences of their lives. They have told me that they are excited to tell their children and grandchildren one day about the experience. Just recently, one of my former students, a Helias graduate, was able to travel to Europe and tour a concentration camp. He immediately contacted me during the experience, sent me videos and brought back documents to share with me. I believe that my lessons and his experience meeting a survivor inspired him to create these additional experiences for himself,” Kempker wrote.

Cavender said as the number of living Holocaust survivors dwindles, “what we’ve been able to do is put together a cadre of what we call second-generation speakers” — children and grandchildren who can tell a loved one’s story, maybe incorporating videotaped testimony in a presentation.

“It’s not perfect, but it can be really effective,” she said of whether that might be the way of the future in incorporating survivors’ testimonies into Holocaust education.

She added there is also expensive — a half-million dollars — hologram-like technology that an audience can interact with recordings of survivors through, and a person on hand with the projection can frame questions from an audience in a way the program can understand.

The museum in St. Louis does not have the technology, but she said the Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center in Skokie, near Chicago, does.

Kempker said it can be difficult to engage students with history, and “Many people debate the value of learning about the Holocaust, saying things like, ‘It’s not like we can change the past.’ To me, that’s not the point. The importance of learning about the past is so that future genocides can be prevented.”