Due to staffing shortages and despite an aggressive hiring campaign, the Missouri Department of Corrections has logged more than 1 million hours of overtime in the first six months of 2018 and spent $16.3 million on overtime-related costs.

By comparison, 1.6 million overtime hours were logged in 2017, and the department paid nearly $21.4 million in overtime-related costs - putting Missouri's prisons on pace to finish 2018 with 400,000 more overtime hours than the previous year.

The 2018 overtime expenditures include balances earned in 2017 that were paid in January and June, Corrections department spokesman Karen Pojmann said. The expenditures also include two large, lump-sum payments of overtime balances. Pojmann said the department was unable to specify the amount of the lump-sum payments due to antiquated computer systems.

Staff members who work overtime have the option to earn comp time or to be paid for the overtime, she said. Some staff choose to accrue comp time up to a certain limit. Every January, the department makes lump-sum overtime payouts for accrued time beyond 80 hours. If funds are available, the department makes a second lump-sum payout in June.

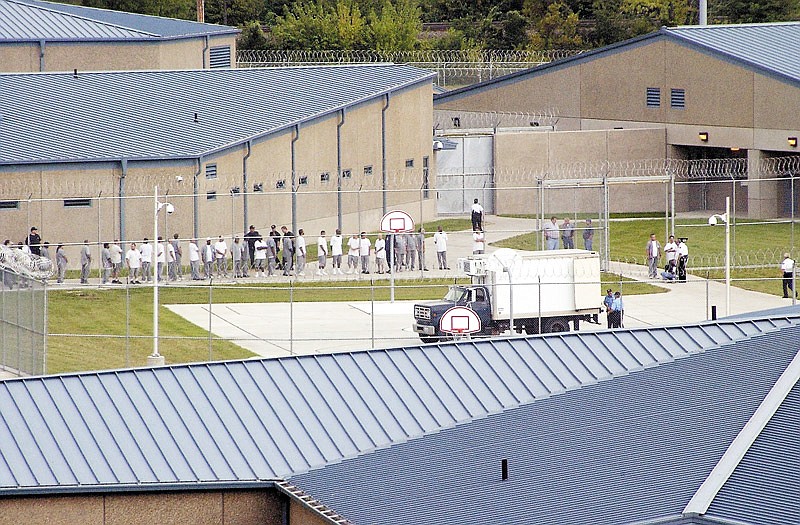

Staffing shortages at Missouri's prisons are driving up overtime totals, the department has acknowledged. The shortages have led the department to restrict activities of inmates.

Those restrictions are resulting in rising inmate tensions and were cited as the underlying cause of inmate protests at the Crossroads Correctional Center in Cameron in May and the Tipton Correctional Center on July 4, said Gary Gross, director of the Missouri Corrections Officers Association. He said the organization's members have been seeing the rising tensions at the state's prisons and that the problems will get worse unless the state does something to help bring in more officers - through higher pay and benefits.

The staffing situation became critical in the last year, Gross said. With a good job market now, he said, people can find more desirable jobs with better benefits, compared to a $14-an-hour starting corrections officer's salary.

"This is a message we've taken to the Legislature the past few years as conditions have declined," Gross said. "A lack of adequate pay and loss of benefits has put us in this position. A big issue is that the central office of the department doesn't have the authority to fix some of these issues."

That authority to deal with issues of better pay and benefits falls to the Legislature, he said.

The Corrections has more than 11,200 corrections employee positions throughout the state. Earlier this month, there were 700 open starting-level corrections officer positions statewide with a total of around total 5,000 corrections officers positions. About 89 percent of the department's entry-level corrections officer positions are filled statewide, Pojmann said.

Pojmann said she could not discuss the staffing numbers, patterns and ratios for each of the state's prisons because it could create a security risk.

Gross couldn't give exact numbers but said officers and staff are "working enormous amounts of overtime."

"Our members have said there are some institutions where officers have worked three or four overtime shifts in a week," he said.

Pojmann acknowledged the department has requested - and mandated - overtime of prison staff so the prisons remain adequately staffed for safety.

"Many of our facilities do not need to resort to mandatory overtime, but some do," she said. "When overtime work is necessary to ensure the safety and security of an institution, our first step is to seek volunteers willing to work overtime. These can include corrections officers at the facility in question, corrections officers from other facilities, or department employees who are trained and certified as corrections officers but are employed in other positions."

When they have to make overtime mandatory, Pojmann said, they try to accommodate the needs of each staff member. Staff members who are sick may use sick time if they are unable to make it to regular shifts or overtime shifts, but disciplinary action might take place if staff members are chronically absent (from regular and/or overtime shifts) or have other attendance issues, she said.

Gross has said non-custody staff are being pushed into corrections officer roles due to the staffing problems.

But Pojmann emphasized no untrained non-custodial officers have been used as corrections officers.

"Anyone working overtime as a corrections officer has been trained to work as a corrections officer and has previously worked as a corrections officer," she said. "Some of those people might have different full-time jobs in the department now. For example, there's a staff member who works in our central office in a non-custody position. He previously worked as a corrections officer. He keeps his CO training and certification current and sometimes works overtime shifts at Jefferson City Correctional Center as a corrections officer in a custody position. That is not his full-time job, and it is not a requirement of his job. It's something he chooses to do to earn overtime."

CO-trained, non-custodial staff should be used sparingly, Gross suggested.

"There is a limit to what they (non-custodial staff) can take and what is expected of them," Gross said. "They take these jobs not intending to work those type of long hours and under this type of stress."

Corrections Director Ann Precythe said: "We have faced a lot of criticism recently, but we're proud of our staff that we hire; they are hardworking.

"A lot of our staff are former military personnel. We are trying many efforts to support our staff so they know we are keeping people calm because the safety of our staff is foremost, and in turn that will keep our facilities secure," she said.

In addition to offering and sometimes mandating overtime, the department's strategy to address the staffing shortage is to limit the activities of the inmates.

"If we don't have sufficient staff, we unfortunately have to limit the activities of the offenders," Pojmann said. "This can mean shorter recreation periods or reduced programming time."

If activities are limited due to staffing shortages, Pojmann said, recreation is the most likely area to be affected. For example, each housing unit might have reduced recreation time, or the facility might keep the yard open but close the gym and limit movement to other areas.

As an example, the prison populations are on modified lockdown - or restricted movement - at Crossroads and Tipton, where the recent inmate disturbances occurred, she said.

"They aren't on full lockdown, but they haven't returned to a normal routine," Pojmann said. "Offenders are allowed to leave their cells every day. Every day, they have 20 minutes of recreation time, access to showers, access to phone calls and the ability to make health care appointments.

"Normally during the day, offenders would be doing a job at our facilities such as the laundry, grounds upkeep and vocation programs," Pojmann said. " In modified lockdown, you can't do those. Inmates who are needed for essential jobs such as food service are still allowed to do those jobs in modified lockdown."

Precythe, the director, said the department has increased efforts to hire more corrections officers.

She said the department is using social media platforms to spread the word about job availability and is offering financial incentives to current employees who refer candidates who are hired.

"When you don't have competitive wages, it makes recruiting so much tougher," Precythe said. "Missouri is the lowest-paid state for correctional officer pay. I have been talking with legislators and the governor about what to do to increase officer pay and all employees within the department. The problem is that the solution won't happen overnight."

Pojmann, the department spokeswoman, said the Corrections department has launched several programs to attract new employees and to retain staff. But even with those efforts, the robust job market makes it a challenge to find the right people for prison jobs.

The department had hired 75 people in December, 82 in January, 49 in February, 94 in March, 131 in April and 30 in May, Pojmann said. The department isn't tracking how many staff members leave the department after completing training.

The Corrections department is pursuing other solutions to ease the burdens on the prison system, Precythe said. She cited initiatives to release non-violent offenders.

"Our parole board wants to release the right people from prison, and I believe we have to continue with justice reinvestment," she said. "Our prisons have been bursting at the seams long before the staff position vacancies became a real situation. It's the right thing to do, but the vacancy issue has made it more complex."

Precythe said the department also has been moving some inmates to prisons that are more fully staffed. She declined to define what she considered to be a "well staffed" level. Most of the state's prisons - including Jefferson City Correctional Center, Algoa Correctional Center and Tipton - are "more fully staffed," she said.

"We take the concerns of our offenders, offender families, staff and their families very seriously," Precythe said. "Our recruiters are doing a good job; it's just that with a very healthy job market, we can't bring in people fast enough to get positions filled like we'd like to."

Gross acknowledged the solution is elusive.

"I think they (department leadership) do take these issues seriously, but how do you fix it?" Gross said. "This is going to take a major commitment from the Legislature, and it's probably going to get worse before it gets better."

Correction: Information reporting employee staffing numbers in this story has been updated. Information in an earlier version of this article was incorrect.