Hospital consolidation is a reality of the American health care system - reflected in the proposed sale of SSM Health's St. Mary's Hospital facilities in Jefferson City and Mexico to MU Health - but there is increased scrutiny nationwide over consolidations' effects on costs for patients.

SSM and MU Health announced in August they were negotiating the possible sale of St. Mary's and the hospitals' associated clinics, following SSM's decision to leave the Mid-Missouri marketplace.

Jeffrey Patrick, president of the Jefferson City Medical Group, said JCMG and other community members "oppose the acquisition of St. Mary's Hospital by MU Health Care because we value choice for both physicians and patients, and we appreciate the ability to provide health care free from corporate interference."

A community group organized to oppose the proposed sale suggests a dose of skepticism is warranted.

"A healthy sense of skepticism is important when a CEO tells a community that patient access to care will increase and costs will remain the same once its competition is eliminated and subsequently replaced by a government-backed monopoly," said Connie Farrow, the spokeswoman for the Coalition for Choice.

But leaders of MU Health and SSM Health have said they support competition and that it would remain after a sale of St. Mary's to MU Health.

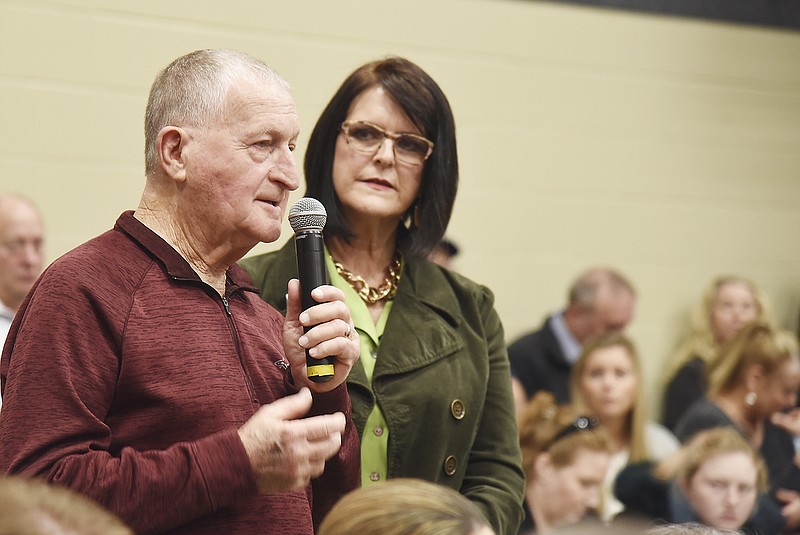

"There will be massive - there is massive competition right now," Jonathan Curtright, MU Health's chief executive officer, said last Monday at a public forum on the proposed sale of St. Mary's. "If you think about it, there is so much competition relative to physician groups.

"There is competition for ambulatory surgery centers; there are two cancer centers here; there are imaging centers here. There is massive competition here. The challenge is the traditional in-patient services, that's where it isn't working financially right now."

SSM Health's Chief Operating Officer Steve Smoot said there's "robust competition in the outpatient world. Folks, I'm telling you, I'm sorry to have to deliver this message, but consolidation of hospital beds is happening all over the country. It is the reality of the times we're in."

'Highly concentrated' hospital markets

PricewaterhouseCoopers' Health Research Institute published in June a report that estimates that by 2019, 93 percent of most metropolitan hospital markets in the United States will be considered "highly concentrated" as a result of mergers - an increase from 65 percent in 1990, 77 percent in 2006, and 84 percent in 2012.

PricewaterhouseCoopers is a London-headquartered professional services company that offers services including audit and assurance, tax and consulting.

"In the short term, this trend likely will lead to higher prices for medical services in these markets as providers have more negotiating power with payers and increased expenses from integration," according to HRI's report.

The report added 2017's number of announced hospital and health system deals "increased nearly 13 percent from 2016, the highest number of transactions since 2000. Of 115 health system and hospital mergers announced in 2017, 10 were mega-deals involving sellers with net annual revenues of at least $1 billion. The intent of these deals is to achieve scale to invest in the infrastructure and programs necessary to drive quality, convenience and customer satisfaction, and ultimately deliver value to consumer, employers and health insurers. The short-term result is often higher prices."

A recent analysis conducted for the New York Times by the Nichols C. Petris Center at the University of California, Berkeley, found among the 25 metropolitan areas in the U.S. with the highest rates of hospital consolidation from 2010-13, the average price of a hospital stay increased 11-54 percent in the following years - and in at least 14 metro areas, that increase was greater than that seen in the rest of the state.

Other studies - such as from the American Hospital Association - support conclusions that mergers do, however, lead to decreases in hospital costs.

The News Tribune asked MU Health and SSM Health to comment on the New York Times' reporting on the Petris Center analysis - featured in the Nov. 14 story headlined "When hospitals merge to save money, patients often pay more" - and to more specifically explain how a reduction in health care inefficiencies, such as through a consolidation, leads to reduced patient costs, and where and how patients could expect to notice reduced costs.

Both organizations deferred to the Missouri Hospital Association. However, in a later interview with the News Tribune, Curtright said an increase in efficiency makes hospitals more competitive for insurance contracts, and more competitive costs for specialty services attracts consumers, who in turn apply pressure on insurance providers to include their local hospital in their contracts.

The News Tribune also reached out specifically to Smoot of SSM with questions for this story, but SSM spokesman Brian Westrich said SSM was not in a position to respond with the holidays and staff taking personal time off.

Federal scrutiny over consolidations

There is increased federal scrutiny over consolidations' effects on health care consumers' costs.

President Donald Trump released an executive order in October 2017 on "promoting healthcare choice and competition across the United States," in which Trump said his administration would "continue to focus on promoting competition in healthcare markets and limiting excessive consolidation throughout the healthcare system."

This month, the secretaries of the U.S. departments of Health and Human Services, the Treasury and Labor jointly announced the release of a report - "Reforming America's Healthcare System Through Choice and Competition" - pursuant to Trump's executive order, prepared by HHS in collaboration with the previously mentioned departments, the Federal Trade Commission and several offices in the White House.

There are many factors that influence health care costs and spending, and in terms of market competition, the Trump administration's report notes "many cases where government regulation and rules prevent healthcare markets from working efficiently," including through third-party payment and a failure to adopt policies that let disruptive technologies such as telehealth compete.

In terms of provider competition, the federal government's report goes so far as to cite evidence - a 2000 study of 500,000 Medicare beneficiaries - that found "those who experienced a heart attack had a statistically significant (1.5 percentage point) higher chance of dying within one year of treatment if they received care in a hospital with fewer potential competitors."

"Economic studies also consistently demonstrate that reducing hospital competition leads to higher prices for hospital care. These effects are not limited to for-profit hospitals: mergers between not-for-profit hospitals can also result in substantial anti-competitive price increases," according the Trump administration's report.

The section of the report on trends in health care market consolidation recommended the administration continue to monitor market competition.

The Washington Post reported this month that health care mergers will also likely be a priority of Democrats once they take control of the U.S. House of Representatives in January.

The News Tribune asked Curtright about the federal push to promote choice and competition in health markets - how he evaluates the process, and all the academic and other studies that can point in different directions on how mergers affect costs.

"I think it's important to note what's going on nationally, when you look at every market in the United States," Curtright said, before he listed cities - Chicago; Des Moines, Iowa; Springfield, Illinois; Kansas City; Denver, Colorado; Atlanta, Georgia.

"More and more of these places - and (the) Twin Cities - are all, or for the most part creating integrated health care systems that are able to decrease the fixed cost of providing that care and are able to spread those costs over more and more volume, if you will. You're much, much more efficient when you're able to do that. It's easier for these larger systems to know and have the resources so their overall quality scores, their safety scores (are) much more easy to demonstrate for the care they provide," he said.

"I think that to ignore what is happening nationally - we're doing that at our own peril. There's a reason that every system, or seemingly every city in the United States, has got systems that are trying to grow and are trying to get scale so they make it to be more efficient with the care that they provide," he added.

Next steps

People with more questions or who want to provide additional feedback on the proposed sale of St. Mary's to MU Health can do so at muhealth.org/ssm.

On whether there will be more public forums led by MU Health, SSM Health or both, Curtright said, "Perhaps. I think that the next step is going to be getting in front of the Audrain and St. Mary's employees - the group that I desperately want to chat with."

"We are genuinely concerned about the anxiety and lack of information that the employees at St. Mary's and Audrain Medical Center have gotten, and we need to do a better job, both at SSM and MU Health Care of telling that story and making sure that their voice is heard," he said.

"There won't be any community forums scheduled in the short run, but we will be working very closely with the human resources departments at those two hospitals to make sure that the employees have a chance to have their voice heard in more of a private setting," Curtright added.